[ad_1]

At one point or another, most gymgoers wonder: Does cardio kill gains?

Here’s how it usually goes: You’re training hard, eating well, and getting enough sleep to gain muscle. But to stay fit, you feel you should also do some cardio, even if it’s just for an hour or two each week.

The worry is that while cardio is good for your health, it might also diminish your muscle and strength gains.

But is that really true?

Does cardio make you lose muscle mass?

Or have the “muscle-burning effects” of cardio been exaggerated by online fitness “gurus?”

In this article, you’ll learn the answer. You’ll also discover the mistakes people make that can increase your odds of cardio burning muscle, how to combine cardio and weightlifting correctly, and more.

Does Cardio “Destroy” Gains?

When people ask, “Does cardio lose muscle mass?”, what they really mean is “Does cardio break down the contractile proteins that make up your muscles?”

And the answer is it can if you do almost everything wrong with your diet and training.

In other words, cardio won’t hamper your gains if you eat and train properly. In fact, it will likely improve your health and fitness in numerous ways.

Let’s discuss the six most common mistakes people make that increase the odds cardio burns muscle.

Mistake #1: Doing cardio instead of lifting weights.

Although many people blame aerobic exercise for burning muscle, a lack of weightlifting is more often the problem.

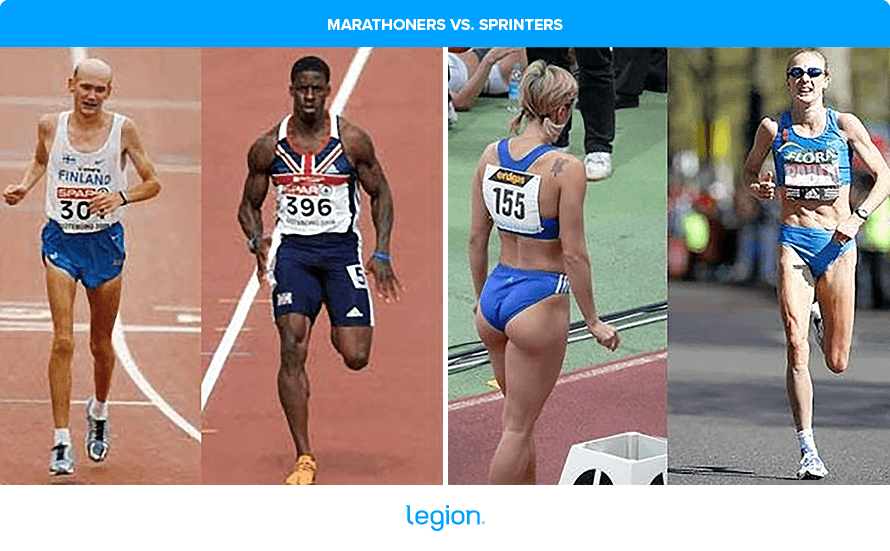

Fitness influencers often make misleading comparisons between marathon runners, who are typically very lean, and sprinters, who are usually muscular. They suggest that doing lots of slow-paced, steady-state cardio will make you skinny, while focusing on weightlifting without much cardio will make you look like a bodybuilder.

This line of reasoning is how you get pictures like these:

Of course, this argument ignores several facts:

- Many endurance athletes don’t lift weight, or if they do, they train with light weights and infrequently.

- Top-level endurance athletes train much more intensely than the average person trying to stay fit. For example, champion marathoners run up to 160 miles per week—over 20 miles daily!

- These athletes often have an unhealthy obsession with keeping their weight as low as possible to improve performance, which can include significantly limiting their calorie intake.

- Sprinters often train with heavy weights and may use steroids to improve their performance, which isn’t common for endurance athletes.

Basically, the only thing these comparison pictures prove is that running marathons, severely restricting your calorie intake, and not lifting weights is a recipe for staying small.

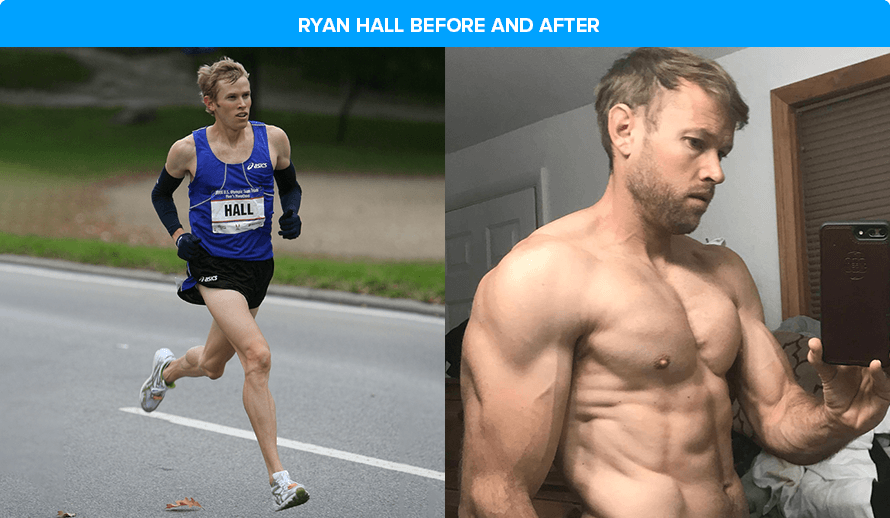

But what if an endurance athlete starts eating more and lifting weights?

After retiring from elite-level marathoning, Ryan Hall did just that. Here’s how his body changed:

The lesson?

Doing lots of cardio at the expense of proper weightlifting can burn muscle, but this is an easy mistake to avoid, provided you lift weights and eat enough calories and protein.

Mistake #2: Doing cardio as part of a crash diet.

Many people who do lots of cardio also follow a crash diet to lose weight as fast as possible.

And this works extremely well.

The problem is, this also leads to significant muscle loss, which means these people wind up looking skinny fat.

And when this happens, they blame cardio.

The truth is, any form of extreme calorie restriction—whether from eating less, doing lots of cardio, or both—leads to muscle loss, especially if you’re not lifting weights.

But the reckless calorie restriction is at fault—not cardio

Mistake #3: Running too much.

Does running burn muscle?

Sort of.

Running causes more muscle damage than other forms of cardio, like cycling, rowing, and rucking, which interferes with muscle gain in two ways:

- It significantly increases muscle protein breakdown during and after runs, making it harder for your body to build new muscle proteins.

- It causes disproportionately more fatigue than other kinds of exercise, which can interfere with your strength training workouts.

However, this doesn’t mean running will always hinder your muscle-building efforts.

To avoid any issues, simply limit your running to no more than 2-to-3 hours of running per week, and make sure you do your running and lower-body weightlifting on separate days.

Mistake #4: Doing too much total cardio.

Your body has a limited capacity to recover from training, and if you’re already lifting weights 3-to-5 times weekly, piling on several hours of cardio might be too much.

Again, however, the issue isn’t cardio itself but how much you do.

Research shows that so long as you’re following a proper diet and strength training program, you can gain muscle just as effectively doing a few hours of cardio per week as you can when only lifting weights.

To ensure you don’t do too much cardio, here are some guidelines that work for most people:

- Limit the time you spend doing cardio to no more than half the time you spend weightlifting. For instance, if you lift weights for 4 hours per week, don’t do more than 2 hours of cardio.

- Keep most of your cardio workouts to 45 minutes or less.

- Don’t do more than one HIIT cardio workout per week.

Mistake #5: Doing too much cardio at one time.

The total amount of cardio you do each week isn’t the only factor that can impact muscle growth; the length of each cardio session matters, too.

Research suggests that to avoid the negative effects of cardio on muscle growth, it’s best to keep most of your cardio workouts shorter than an hour. Going beyond an hour doesn’t mean you’ll automatically start losing muscle, but it does increase the chance of negatively affecting muscle growth.

Further support for this comes from studies of natural bodybuilders, who often do several 30-to-40-minute cardio workouts per week without losing significant muscle.

Thus, so long as you keep most of your cardio workouts under an hour, you don’t need to worry about burning muscle.

Mistake #6: Doing exhausting cardio immediately before, during, or after lifting weights.

A common mistake when combining weightlifting and cardio is to do both in the same workout.

Some people run for 30 minutes before or after lifting weights, or mix in cardio with weightlifting, like in CrossFit or circuit training.

However, these approaches are not ideal for maximizing muscle growth.

Doing cardio immediately or even several hours before lifting weights makes it difficult to perform at your best in the gym, which usually results in less muscle growth over time.

Doing cardio immediately after lifting weights is less detrimental, but can also interfere with muscle growth by dampening some of the “muscle-building” signals from strength training.

Thus, it’s generally better to avoid cardio immediately after lifting weights to allow your body to fully benefit from the strength training.

That said, if the only time you can do cardio is right after lifting, don’t sweat it. As long as your post-lifting cardio workouts are fairly short and low-intensity, they shouldn’t get in the way of muscle building.

It’s also worth noting that not all forms of cardio have the same impact. Walking 10-to-20 minutes to the gym won’t hurt your gains. Doing an intense 30-minute HIIT workout and then clomping from the treadmill to the squat rack will.

The Right Way to Combine Cardio and Strength Training

So, does cardio burn muscle?

No.

If you do cardio incorrectly, it can slow your rate of muscle growth, but it won’t make you lose muscle if you sidestep the most common blunders.

Here’s how to do that:

- Prioritize low-impact forms of cardio like cycling, rowing, and rucking.

- Limit the volume and duration of your cardio workouts to no more than 30-to-45 minutes per cardio workout and two-to-three hours of total cardio per week.

- Do cardio and weightlifting on separate days. If that isn’t possible, lift weights first and try to separate the two workouts by at least 6 hours.

[Read More: Concurrent Training: The Right Way to Combine Cardio and Strength Training]

Does Cardio Kill Gains?: FAQs

FAQ #1: Does fasted cardio burn muscle?

“Fasted cardio” is cardio done after your body has fully digested your last meal (usually 5-to-6 hours after eating).

While fasted cardio increases fat burning during your workout, it causes two problems:

- You burn less fat during the rest of the day, which means you lose the same amount of total body fat over a 24-hour period as you do after fed cardio.

- Your risk of muscle loss rises.

The main reason fasted cardio can cause muscle loss is that it quickly depletes muscle glycogen levels, prompting your body to break down protein (muscle) for energy.

However, you generally have to do a fair amount of cardio—at least 60 minutes or more—to deplete glycogen levels. So, the risk of muscle loss from a short, ~30-minute fasted cardio session is low.

To learn more about the pros and cons of fasted cardio, check out this article:

What Is Fasted Cardio and Can It Help You Lose Weight?

FAQ #2: Does high-intensity cardio burn muscle?

No, high-intensity cardio doesn’t burn muscle any more than traditional cardio does, as long as you avoid the mistakes above.

While some people claim that high-intensity cardio is less likely to burn muscle, the evidence for this is inconsistent.

There’s reason to believe high-intensity cardio is slightly more likely to interfere with muscle growth than low-intensity cardio. This is because it often leads to more muscle damage and fatigue, which can negatively impact your strength training and muscle gains over time.

Thus, you might want to lean towards low-intensity cardio most of the time if you’re focusing on building muscle.

FAQ #3: How can I do cardio without losing muscle?

The best way to combine cardio and weightlifting without losing muscle is to follow these guidelines:

- Limit the time you spend doing cardio to no more than half the time you spend weightlifting. For instance, if you lift weights for 4 hours per week, don’t do more than 2 hours of cardio.

- Keep most of your cardio workouts to 30-to-45 minutes.

- Don’t do more than one HIIT cardio workout per week.

+ Scientific References

- Tjelta, Leif Inge. “The Training of International Level Distance Runners.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, vol. 11, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 122–134, journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1747954115624813, https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954115624813.

- Karrer, Yannis, et al. “Disordered Eating and Eating Disorders in Male Elite Athletes: A Scoping Review.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, vol. 6, no. 1, Oct. 2020, p. e000801, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000801. Accessed 10 Dec. 2020.

- Reel, Justine J., et al. “Weight Pressures in Sport: Examining the Factor Structure and Incremental Validity of the Weight Pressures in Sport — Females.” Eating Behaviors, vol. 14, no. 2, Apr. 2013, pp. 137–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.003. Accessed 27 Jan. 2020.

- Kampouri, Dimitra, et al. “Prevalence of Disordered Eating in Elite Female Athletes in Team Sports in Greece.” European Journal of Sport Science, vol. 19, no. 9, 17 Mar. 2019, pp. 1267–1275, https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1587520. Accessed 8 Jan. 2021.

- Bolger, Richard, et al. “Sprinting Performance and Resistance-Based Training Interventions.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 29, no. 4, Apr. 2015, pp. 1146–1156, journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/FullText/2015/04000/Sprinting_Performance_and_Resistance_Based.38.aspx, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000000720.

- Calbet, J. A. L., et al. “A Time-Efficient Reduction of Fat Mass in 4 Days with Exercise and Caloric Restriction.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 25, no. 2, 6 Mar. 2014, pp. 223–233, https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12194. Accessed 20 Sept. 2021.

- Cava, Edda, et al. “Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss.” Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal, vol. 8, no. 3, May 2017, pp. 511–519, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5421125/, https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.014506.

- Millet, Guillaume Y, and Romuald Lepers. “Alterations of Neuromuscular Function after Prolonged Running, Cycling and Skiing Exercises.” Sports Medicine, vol. 34, no. 2, 2004, pp. 105–116, https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200434020-00004. Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Sale, D. G., et al. “Comparison of Two Regimens of Concurrent Strength and Endurance Training.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 22, no. 3, 1 June 1990, pp. 348–356, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2381303/. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

- Murach, Kevin A., and James R. Bagley. “Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy with Concurrent Exercise Training: Contrary Evidence for an Interference Effect.” Sports Medicine, vol. 46, no. 8, 1 Mar. 2016, pp. 1029–1039, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0496-y.

- Kilen, Anders, et al. “Impact of Low-Volume Concurrent Strength Training Distribution on Muscular Adaptation.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, vol. 23, no. 10, Oct. 2020, pp. 999–1004, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.03.013. Accessed 22 May 2022.

- Er, Helms, et al. “Recommendations for Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Resistance and Cardiovascular Training.” The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 1 Mar. 2015, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24998610/.

- Baar, Keith. “Using Molecular Biology to Maximize Concurrent Training.” Sports Medicine, vol. 44, no. S2, 30 Oct. 2014, pp. 117–125, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0252-0. Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Davitt, Patrick M., et al. “The Effects of a Combined Resistance Training and Endurance Exercise Program in Inactive College Female Subjects.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 28, no. 7, July 2014, pp. 1937–1945, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000000355.

- SCHUMANN, MORITZ, et al. “Fitness and Lean Mass Increases during Combined Training Independent of Loading Order.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 46, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1758–1768, https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000303. Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Vieira, Alexandra Ferreira, et al. “Effects of Aerobic Exercise Performed in Fasted v. Fed State on Fat and Carbohydrate Metabolism in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 116, no. 7, 9 Sept. 2016, pp. 1153–1164, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/effects-of-aerobic-exercise-performed-in-fasted-v-fed-state-on-fat-and-carbohydrate-metabolism-in-adults-a-systematic-review-and-metaanalysis/0EA2328A0FF91703C95FD39A38716811, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114516003160.

- Schoenfeld, Brad. “Does Cardio after an Overnight Fast Maximize Fat Loss?” Strength & Conditioning Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, 1 Feb. 2011, pp. 23–25, journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Fulltext/2011/02000/Does_Cardio_After_an_Overnight_Fast_Maximize_Fat.3.aspx, https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0b013e31820396ec. Accessed 6 July 2020.

- Paoli, Antonio, et al. “Exercising Fasting or Fed to Enhance Fat Loss? Influence of Food Intake on Respiratory Ratio and Excess Postexercise Oxygen Consumption after a Bout of Endurance Training.” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, vol. 21, no. 1, Feb. 2011, pp. 48–54, https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.21.1.48.

- Lemon, P. W., and J. P. Mullin. “Effect of Initial Muscle Glycogen Levels on Protein Catabolism during Exercise.” Journal of Applied Physiology: Respiratory, Environmental and Exercise Physiology, vol. 48, no. 4, 1980, pp. 624–629, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7380688/, https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1980.48.4.624.

- Fyfe, Jackson J., et al. “Interference between Concurrent Resistance and Endurance Exercise: Molecular Bases and the Role of Individual Training Variables.” Sports Medicine, vol. 44, no. 6, 12 Apr. 2014, pp. 743–762, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0162-1.

- Wilson, Jacob M., et al. “Concurrent Training: A Meta-Analysis Examining Interference of Aerobic and Resistance Exercises.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 8, Aug. 2012, pp. 2293–2307, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e31823a3e2d.

- Howatson, Glyn, and Adi Milak. “Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage Following a Bout of Sport Specific Repeated Sprints.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 23, no. 8, Nov. 2009, pp. 2419–2424, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181bac52e. Accessed 8 May 2019.

- Sabag, Angelo, et al. “The Compatibility of Concurrent High Intensity Interval Training and Resistance Training for Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 36, no. 21, 16 Apr. 2018, pp. 2472–2483, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1464636. Accessed 27 Mar. 2019.

[ad_2]

Source link