[ad_1]

The hack squat is a lower-body exercise involving a hack squat machine.

It’s a go-to exercise for many gym-goers because it trains your entire lower body without stressing your knees and back as much as other free-weight squatting exercises.

What’s more, it helps you develop lower-body strength, power, speed, and agility, making it an excellent option for athletes.

In this article, you’ll learn what the hack squat (and hack squat machine) is, why it’s beneficial, the muscles worked by the hack squat, how to perform proper hack squat form, the best hack squat

What Is A Hack Squat?

The hack squat is a lower-body strength training exercise.

Originally, weightlifters performed the hack squat by placing a loaded barbell behind their heels, squatting down, gripping the barbell, then standing up. In fact, this is how the exercise got its name—”hack” comes from the German word “hacke,” which translates to “heel.”

Nowadays, however, most people prefer the machine hack squat to the barbell hack squat. As such, the machine hack squat is the variation we’ll focus on in this article.

The machine hack squat involves a hack squat machine, which is a piece of workout equipment that supports your back while you perform the exercise and makes adding weight more straightforward.

Hack Squat vs. Leg Press: Which Is Better?

It depends.

The hack squat trains your quads through a greater range of motion, which means it’s likely slightly better for training your quads than the leg press.

However, the leg press is less taxing on your lower back and generally less fatiguing overall. This makes it more suitable for people with lower-back issues and for training your legs at the end of a workout when you’re already feeling ragged.

Of course, there’s no reason to include just one of these exercises in your program—the best solution for most people is to do both (or to do the leg press or hack squat and another squat variation).

A good way to do this is to include the hack squat in your program for 8-to-10 weeks of training, take a deload, then replace the hack squat with the leg press for the following 8-to-10 weeks of training.

Then, you can either continue alternating between the exercises every few months like this or stick with the one you prefer.

This is how I personally like to organize my training, and it’s similar to the method I advocate in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about what exercises to include in your training program to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

Hack Squat vs. Squat: Which Is Better?

It depends.

The hack squat and back squat are both effective exercises for training all the muscles of the legs, though the barbell squat is likely better at training stabilizer muscles across your entire body and secondary muscle groups such as the lower back.

That said, some people lack the mobility to perform the back squat properly or can’t perform it because of preexisting injuries that make it unsafe or uncomfortable.

For these people, the hack squat is a better option, at least until they develop the mobility to perform the back squat with proper form or recover from their injury.

In most cases, there’s no reason to choose just one of these exercises, though. The best solution for most people is to include both exercises in their program.

A good way to do this is to start your leg workout with the back squat, then perform the hack squat later in your workout when supporting muscles like your lower back are bushed, but your legs can still manage another few sets.

Hack Squat: Benefits

1. It trains your entire lower body.

Many people think you perform the hack squat for quads.

While it’s true that the hack squat is a highly effective quad exercise, it also trains your entire lower body, including the glutes, hamstrings, and calves. It also trains your core and lower back to a lesser degree, too.

2. It’s more joint-friendly than other lower-body exercises.

Research shows that the hack squat places less stress on your spine and knees than other lower-body exercises, including the front, back, and sumo squat.

As such, the hack squat is an excellent lower-body exercise for people who are training around or trying to avoid reaggravating a back or knee injury and find other free-weight squatting exercises uncomfortable.

3. It may improve athletic performance.

Research shows that the hack squat helps you develop lower-body strength, power, speed, and agility, which makes it an excellent exercise for athletes who play sports that require you to jump, sprint, or change direction at speed.

Hack Squat: Foot Placement

Many people believe that changing your foot placement on the hack squat machine greatly influences which lower-body muscles the hack squat emphasizes.

There may be a kernel of truth to this idea, but it’s still more wrong than right.

There’s no research investigating how hack squat feet position affects muscle growth specifically. However, scientists have looked at how altering your foot position during the leg press and squat affects muscle activation.

Since the hack squat, leg press, and squat are similar lower-body exercises, we can likely use the results of these studies to understand the effect of changing your foot placement on the hack squat.

For instance, research shows that placing your feet high on the leg press machine’s footplate (so your toes almost hang off the top) increases glute and hamstring activation, and placing your feet low on the footplate (so your heels almost hang off the bottom) increases quad activation.

In both cases, however, the difference in activation is slight. And since more muscle activation doesn’t always mean more muscle growth, it isn’t clear how much changing the height of your foot placement affects your long-term results.

Things are even more ambiguous when it comes to stance width and foot orientation.

While most leg press research shows that muscle activation in your legs is the same regardless of how wide your stance is or how you point your toes, some squat studies show that taking a wider stance emphasizes your glutes and hamstrings, taking a narrower stance preferentially trains your quads, and pointing your toes out increases activation in your adductor longus (inner thigh muscles).

Again, though, these studies only measure muscle activation, not muscle growth, which makes it difficult to say whether tinkering with your stance width and foot orientation has a meaningful effect on long-term muscle gains.

With this in mind, the most stable, effective, and comfortable hack squat foot placement for most people will be one that places your feet halfway up the footplate, a little wider than shoulder-width apart, and with your toes pointing slightly outward.

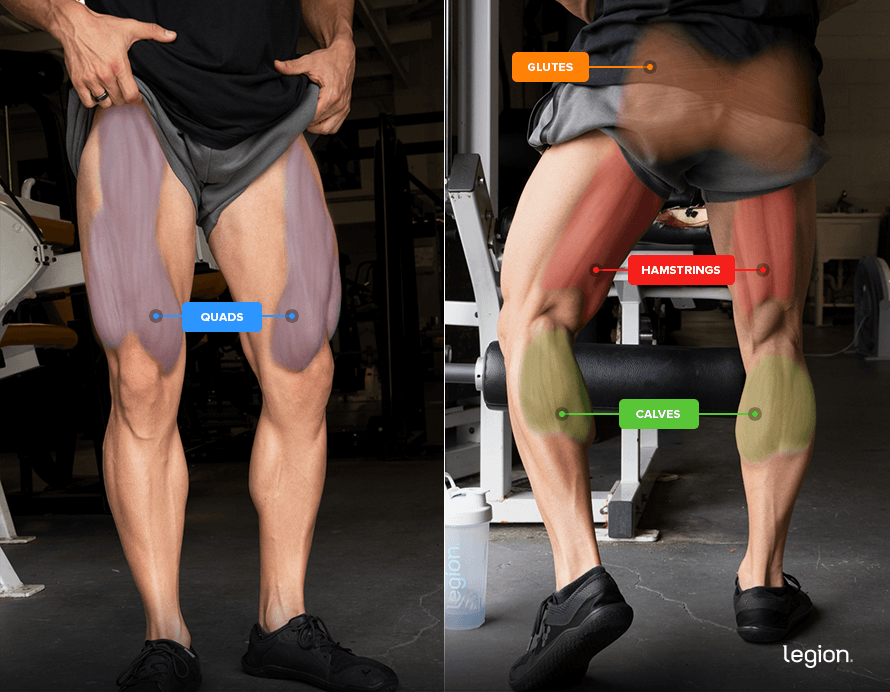

Hack Squat: Muscles Worked

The main muscles worked by the hack squat are the . . .

- Quadriceps

- Hamstrings

- Glutes

- Calves

It also trains the core and lower back to a lesser extent, too.

Here’s how the main muscles worked by the hack squat look on your body:

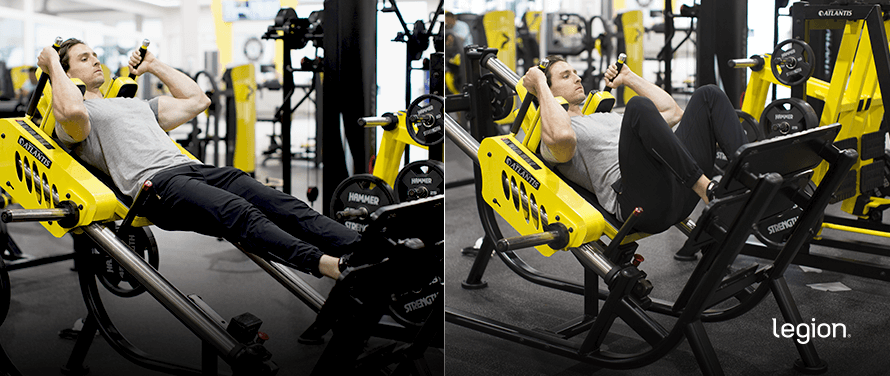

Hack Squat: Form

The best way to learn how to hack squat is to split the exercise into three parts: set up, descend, and squat.

1. Set up

Load the hack squat machine with the desired amount of weight, then position your feet shoulder-width apart on the footplate with your toes pointed slightly outward, your shoulders against the shoulder pads, and your back against the backrest.

Grab the safety handles, then straighten your knees and use the handles to release the weight.

2. Descend

Take a deep breath into your stomach and brace your abs, then while keeping your back pressed against the backrest, lower your body by bending your knees. Allow your knees to move forward in the same direction as your toes.

Keep lowering your body until the angle between your calves and thighs is 90 degrees or slightly less.

3. Ascent

Drive your feet into the footplate and straighten your knees to return to the starting position. This is a mirror image of what you did during the descent.

Here’s how proper hack squat form should look when you put all of this together:

The Best Hack Squat Alternatives

1. Reverse Hack Squat

The reverse hack squat is the same as the regular hack squat, except you perform the exercise facing the machine rather than away from it.

By performing the exercise while facing the machine you shift the emphasis to your posterior chain (the muscles on the back of your body), which makes the reverse hack squat a good alternative for those looking to develop their glutes and hamstrings more than their quads.

2. Barbell Hack Squat

The barbell hack squat allows you to train the same muscles to a similar degree as the machine hack squat, making it an excellent hack squat substitute when you don’t have access to a hack squat machine.

3. Landmine Hack Squat

The landmine hack squat is a hack squat variation that uses a landmine attachment and barbell in place of a hack squat machine. Similarly to the regular hack squat, the landmine hack squat trains all of your lower-body muscles, which makes it a viable alternative if you want to change up your training.

4. Smith Machine Hack Squat

If your gym doesn’t have a hack squat machine, the Smith machine hack squat is a worthy alternative. That’s because it allows you to train the same muscles to a comparable degree. Furthermore, because you use a Smith machine, it’s as stable and easy to control as the regular version.

5. Front Squat

The front squat isn’t a hack squat variation, per se, but a free-weight alternative to the hack squat that trains the same muscles.

FAQ #1: Can you do a hack squat without a machine?

Yes.

The best alternative to the hack squat that doesn’t require a hack squat machine is the barbell hack squat.

To perform the barbell hack squat, place a loaded barbell behind your legs, squat down and grip the barbell, then stand up.

FAQ #2: Where can I learn how to use a hack squat machine?

To learn how to use a hack squat machine, follow the instructions above.

Or, if you’d prefer more hands-on instruction, speak to a trainer at your gym. They should be able to show you how to use your gym’s hack squat machine and explain how to use proper hack squat form.

FAQ #3: Pendulum Squat vs. Hack Squat: What’s the Difference?

The pendulum squat is a lower-body exercise that uses the pendulum squat machine.

The main difference between the pendulum squat and hack squat is the pendulum squat machine is configured so that the exercise is most challenging at the top of each rep and easiest at the bottom.

This is the opposite of the hack squat (and all other squat exercises), which means the pendulum squat trains your lower body slightly differently.

That’s not to say the pendulum squat is better—both exercises train the same muscles equally well, so if you have access to a pendulum squat machine, it’s sensible to include both exercises in your program.

+ Scientific References

- Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J. Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Medicine. 2020;8(8):205031212090155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120901559

- Kubo K, Ikebukuro T, Yata H. Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes. European Journal of Applied Physiology. Published online June 22, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04181-y

- Clark DR, Lambert MI, Hunter AM. Trunk muscle activation in the back and hack squat at the same relative loads. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. Published online July 2017:1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000002144

- Erdağ D, Ulaş Yavuz H. Evaluation of Muscle Activities During Different Squat Variations Using Electromyography Signals. ResearchGate. Published January 2020. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337400852_Evaluation_of_Muscle_Activities_During_Different_Squat_Variations_Using_Electromyography_Signals

- Schwarz NA, Harper SP, Waldhelm A, McKinley-Barnard SK, Holden SL, Kovaleski JE. A Comparison of Machine versus Free-Weight Squats for the Enhancement of Lower-Body Power, Speed, and Change-of-Direction Ability during an Initial Training Phase of Recreationally-Active Women. Sports. 2019;7(10):215. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7100215

- BLAZEVICH AJ, GILL ND, BRONKS R, NEWTON RU. Training-Specific Muscle Architecture Adaptation after 5-wk Training in Athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2003;35(12):2013-2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000099092.83611.20

- Da Silva EM, Brentano MA, Cadore EL, De Almeida APV, Kruel LFM. Analysis of Muscle Activation During Different Leg Press Exercises at Submaximum Effort Levels. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2008;22(4):1059-1065. doi:https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181739445

- ESCAMILLA RF, FLEISIG GS, ZHENG N, et al. Effects of technique variations on knee biomechanics during the squat and leg press. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2001;33(9):1552-1566. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200109000-00020

- Vigotsky AD, Beardsley C, Contreras B, Steele J, Ogborn D, Phillips SM. Greater Electromyographic Responses Do Not Imply Greater Motor Unit Recruitment and “Hypertrophic Potential” Cannot Be Inferred. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017;31(1):e1-e4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000001249

- Murray N, Cipriani D, O’Rand D, Reed-Jones R. Effects of Foot Position during Squatting on the Quadriceps Femoris: An Electromyographic Study. International journal of exercise science. 2013;6(2):114-125. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4882472/

- Martín-Fuentes I, Oliva-Lozano JM, Muyor JM. Influence of Feet Position and Execution Velocity on Muscle Activation and Kinematic Parameters During the Inclined Leg Press Exercise. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Published online June 4, 2021:194173812110163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/19417381211016357

- Martín-Fuentes I, Oliva-Lozano JM, Muyor JM. Muscle Activation and Kinematic Analysis during the Inclined Leg Press Exercise in Young Females. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(22):8698. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228698

[ad_2]

Source link