[ad_1]

Nowadays, you can’t scroll through socials long before hearing someone tout the benefits of “glute activation exercises.”

According to activation advocates, doing specific exercises to warm up your butt before lower-body workouts helps you engage your glutes more effectively than if you went into your workouts “cold.”

This, they claim, is important because it boosts performance and helps you better develop your butt.

Is this true, though?

Are glute activation exercises necessary?

Or do they just delay you from getting to more productive training?

Get evidence-based answers to these questions and more in this article.

What Are Glute Activation Exercises?

A glute activation exercise is a simple warm-up exercise that purportedly helps your glutes “fire” harder during lower-body workouts.

They rose to prominence in the early 2000s after several esteemed physiotherapists and strength coaches claimed they “remind” your body how to use your glutes—something most people who spend long periods each day sitting have allegedly “forgotten.”

According to these experts, regaining proper use of your glutes is paramount for good physical fitness because it helps prevent muscle imbalances that can lead to lower-back, hamstring, and knee pain and ensures your glutes work optimally during physical activity (while playing sports or lifting weights, for example).

At first blush, this theory seems rational, which explains why the fitness fraternity adopted glute activation exercises wholesale and their popularity has continued to grow since. However, on closer inspection, there are multiple reasons to doubt its veracity.

First, it’s entirely based on anecdotal evidence from physiotherapists. And while these people are experts in their field, their observations aren’t a substitute for scientific evidence.

Second, it assumes that your glutes become less responsive because excessive sitting shortens your hip flexors (the muscles on the front of your hips), inhibiting your glutes’ ability to contract. However, research in this area is inconclusive, which makes it impossible to draw firm conclusions about how hip flexor length and pelvic positioning affect glute activation.

Third, studies generally find that people with back, hamstring, and knee pain have perfectly active rather than dormant glutes.

And fourth, being inactive doesn’t appear to prevent your glutes from working when called upon. A good example of this comes from a study published in the Journal of Applied Physiology, in which 24 men were confined to bed rest for 60 days.

While in bed, the researchers encouraged the men to move as little as possible. To facilitate this, a nurse tended to the men’s every need, including helping them use the bathroom and eat.

During the study, some of the men also did 1 hard set of the leg press 3 times weekly, increasing the weights they lifted as the study progressed.

The results showed that the men who only loafed lost glute muscle, which likely meant their glutes became weaker. Those who exercised, however, gained glute size and strength despite spending only a brief time training each week.

In other words, the men didn’t need to move or use activation exercises to “recall” how to use their glutes. They were perfectly able to activate, strengthen, and grow their glutes, despite spending most of their time supine.

Are glute activation exercises necessary, then?

Are Glute Activation Exercises Necessary?

I’m skeptical about glute activation exercises for a couple of reasons:

- Why would doing easy bodyweight exercises before more challenging ones improve muscle activation in the latter?

- Even if it did, wouldn’t simply using heavier weights accomplish this better, and wouldn’t that extra 10-to-20 minutes of futzing around with a resistance band be better spent just doing more working sets of regular exercises?

Unfortunately, science hasn’t definitively answered these questions yet. Several studies offer some insight, though.

For instance, one study conducted by scientists at St Mary’s University found that weightlifters who performed glute activation exercises before doing the hang high pull (an explosive exercise that resembles the power clean) produced the same or greater force than when they didn’t activate their glutes before exercising.

Interestingly, when they activated their glutes beforehand, they exhibited lower glute activation during the explosive exercise.

The scientists weren’t sure why this was, though they hypothesized that doing glute activation exercises made the communication between the weightlifters’ brains and butts more efficient. As such, their brains could send a weaker signal to their glutes to get an equal or greater response.

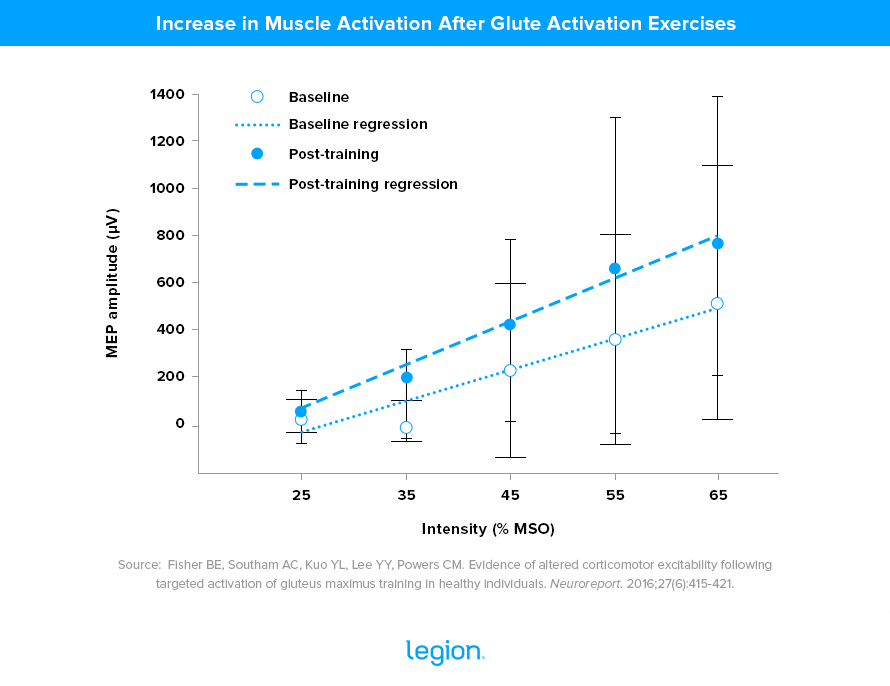

Research conducted by scientists at the University of Southern California lends some credence to this theory.

In this study, the researchers found that people who did a glute activation exercise with bands for one hour per day for a week increased “corticomotor excitability” in the region of the brain responsible for making the glutes contract. Here’s a graph taken from this study illustrating the increase:

In other words, regularly doing glute activation exercises “trained” the people’s brains to better communicate with their glutes, allowing them to activate their glutes more efficiently.

And this may be why some studies show that glute activation exercises can enhance athletic performance.

Contrary to this theory, however, research also shows that regularly doing glute activation exercises increases glute activation during lower-body exercises.

For example, in another study conducted by scientists at the University of Southern California, researchers found that participants who performed glute activation exercises twice daily for a week increased glute activation during the bodyweight squat and split squat by 57% and 53%, respectively.

This isn’t a black mark against glute activation exercises, but it discredits the theory that regularly activating your glutes makes it easier for your brain to talk to your tail end.

Not all glute activation research is quite so peachy.

While some studies suggest that glute activation exercises are a boon for performance, a closer look at their results paints a more ambiguous picture.

For instance, one study conducted at the University of Limerick found that doing glute activation exercises before plyometric (jumping) training improved lower-body power and strength. These improvements didn’t translate into better performance, though (the participants couldn’t jump as high after the activation exercises).

Furthermore, other studies show glute activation exercises offer no benefit to athletic performance.

In a study published in the journal Research in Sports Medicine, researchers found that people who performed glute activation exercises 3 times weekly for 6 weeks didn’t see an increase in glute activation or force production during squats.

Another study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that adding glute activation exercises to a regular dynamic warm-up didn’t improve athletic performance more than doing the regular dynamic warm-up alone.

Should You Do Glute Activation Exercises?

Plenty of studies suggest that glute activation exercises improve athletic performance. The problem is, an equal number show they’re worthless in this regard.

Likewise, it’s debatable whether glute activation exercises increase glute activation during subsequent exercise, with some studies reporting that they do and others showing they make no difference. In any case, it’s unclear what practical value increased activation has.

First, muscle activation only measures the electrical activity of a muscle, not growth. And while muscle activation is necessary for building muscle—no activation always means no growth—it isn’t the best proxy for gauging gains.

For instance, the barbell hip thrust often produces more glute activation than the squat, but due to a variety of factors (shorter range of motion and less stretching of the muscle fibers, mainly), research shows the squat is a better exercise for building your booty.

Second, it’s possible any benefits from the glute activation exercises performed would disappear as you get stronger on exercises like the squat, which will always produce high levels of glute activation.

In other words, while activation exercises might help newbies better stimulate their glutes in their lower-body training, the effect might disappear as they get stronger.

The only other semi-compelling science-based reason to do glute activation exercises is that they may help your head and heinie communicate more efficiently. Research supporting this theory is patchy, though, and there’s little evidence that it boosts muscle growth or performance.

A reasonable counterargument is that activation exercises are simple and stressless, so there’s no downside to trying them out.

And to that, I say suit yourself.

Provided you have the time to perform glute activation exercises, enjoy them, and feel like they benefit your workouts, fill your boots.

Just make sure you follow a sensible glute activation routine . . .

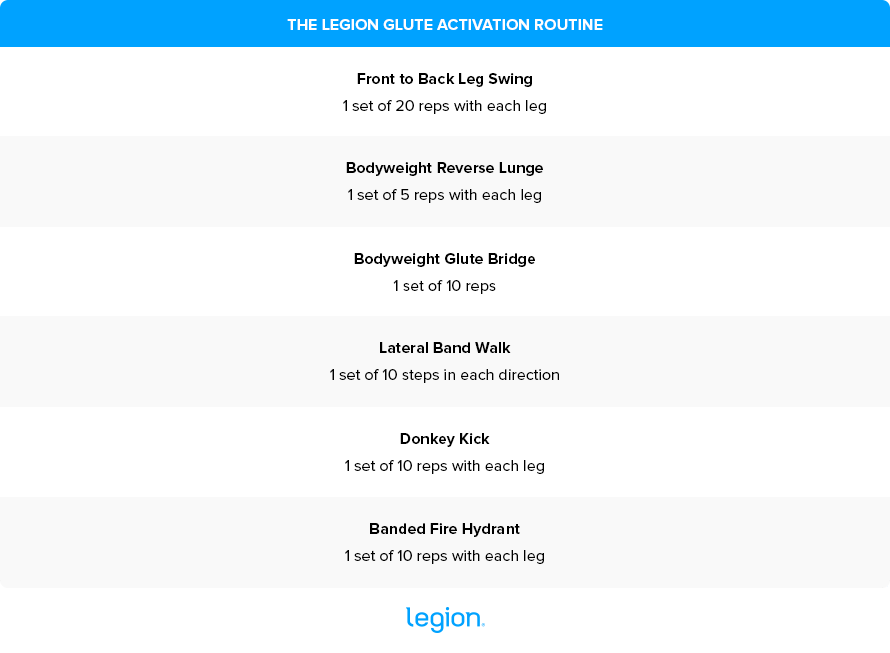

The Best Glute Activation Exercises

The biggest mistake people make when designing a glute activation routine is they include too many exercises, sets, and reps.

You should only do enough to “awaken” your glutes, not fatigue them.

As such, your routine should be short (less than 10 minutes) and include just a handful of the best exercises for glute activation. Here’s what I recommend:

Remember, this routine shouldn’t feel tiring, so allow yourself around 30 seconds between exercises to recover.

And if you want to do glute activation exercises with no equipment (while working out at home or traveling, for example), substitute the set of lateral band walks for another set of the glute bridge and the set of fire hydrants for another set of the donkey kick.

+ Scientific References

- Crone, C. (n.d.). Reciprocal inhibition in man – PubMed. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8299401/

- Van Gelder, L. H., Hoogenboom, B. J., Alonzo, B., Briggs, D., & Hatzel, B. (n.d.). EMG Analysis and Sagittal Plane Kinematics of the Two-Handed and Single-Handed Kettlebell Swing: A Descriptive Study – PubMed. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26618061/

- Mills, M., Frank, B., Goto, S., Blackburn, T., Cates, S., Clark, M., Aguilar, A., Fava, N., & Padua, D. (n.d.). EFFECT OF RESTRICTED HIP FLEXOR MUSCLE LENGTH ON HIP EXTENSOR MUSCLE ACTIVITY AND LOWER EXTREMITY BIOMECHANICS IN COLLEGE-AGED FEMALE SOCCER PLAYERS – PubMed. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26673683/

- Contreras, B., Vigotsky, A. D., Schoenfeld, B. J., Beardsley, C., & Cronin, J. (2015). A comparison of two gluteus maximus EMG maximum voluntary isometric contraction positions. PeerJ, 3(9). https://doi.org/10.7717/PEERJ.1261

- Arab, A. M., Ghamkhar, L., Emami, M., & Nourbakhsh, M. R. (2011). Altered muscular activation during prone hip extension in women with and without low back pain. Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-709X-19-18

- Emami, M., Arab, A. M., & Ghamkhar, L. (n.d.). The activity pattern of the lumbo-pelvic muscles during prone hip extension in athletes with and without hamstring strain injury – PubMed. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24944849/

- Thijs, Y., Pattyn, E., Van Tiggelen, D., Rombaut, L., & Witvrouw, E. (2011). Is hip muscle weakness a predisposing factor for patellofemoral pain in female novice runners? A prospective study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(9), 1877–1882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546511407617

- Miokovic, T., Armbrecht, G., Felsenberg, D., & Belavý, D. L. (2011). Differential atrophy of the postero-lateral hip musculature during prolonged bedrest and the influence of exercise countermeasures. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 110(4), 926–934. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.01105.2010

- Parr, M., Price, P. D., & Cleather, D. J. (2017). Effect of a gluteal activation warm-up on explosive exercise performance. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJSEM-2017-000245

- Fisher, B. E., Southam, A. C., Kuo, Y. L., Lee, Y. Y., & Powers, C. M. (2016). Evidence of altered corticomotor excitability following targeted activation of gluteus maximus training in healthy individuals. Neuroreport, 27(6), 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0000000000000556

- Barry, L., Kenny, I., & Comyns, T. (2016). Performance Effects of Repetition Specific Gluteal Activation Protocols on Acceleration in Male Rugby Union Players. Journal of Human Kinetics, 54(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/HUKIN-2016-0033

- Pinfold, S. C., Harnett, M. C., & Cochrane, D. J. (2018). The acute effect of lower-limb warm-up on muscle performance. Research in Sports Medicine (Print), 26(4), 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2018.1492390

- Achalandabaso-Ochoa, A., Aibar-Almazán, A., Martínez-Amat, A., Pecos-Martín, D., Vidal-Aragón, G., Calderón-Corrales, P., Acuña, Á., & Gallego-Izquierdo, T. (2020). Effects of a Gluteal Muscles Specific Exercise Program on the Vertical Jump. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH17155383

- Cannon, J., Weithman, B. A., & Powers, C. M. (2022). Activation training facilitates gluteus maximus recruitment during weight-bearing strengthening exercises. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology : Official Journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology, 63. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JELEKIN.2022.102643

- Crow, J. F., Buttifant, D., Kearny, S. G., & Hrysomallis, C. (2012). Low load exercises targeting the gluteal muscle group acutely enhance explosive power output in elite athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(2), 438–442. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318220DFAB

- Comyns, T., Kenny, I., & Scales, G. (2015). Effects of a Low-Load Gluteal Warm-Up on Explosive Jump Performance. Journal of Human Kinetics, 46(1), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1515/HUKIN-2015-0046

- Healy, R., & Harrison, A. J. (2014). The effects of a unilateral gluteal activation protocol on single leg drop jump performance. Sports Biomechanics, 13(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2013.872288

- Harrison, A. J., & McCabe, C. (2017). The effect of a gluteal activation protocol on sprint and drop jump performance. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 57(3), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.16.06025-4

- Cochrane, D. J., Harnett, M. C., & Pinfold, S. C. (2017). Does short-term gluteal activation enhance muscle performance? Research in Sports Medicine (Print), 25(2), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2017.1282358

- Sander, A., Keiner, M., Schlumberger, A., Wirth, K., & Schmidtbleicher, D. (2013). Effects of functional exercises in the warm-up on sprint performances. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(4), 995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318260EC5E

- Vigotsky, A. D., Beardsley, C., Contreras, B., Steele, J., Ogborn, D., & Phillips, S. M. (2017). Greater electromyographic responses do not imply greater motor unit recruitment and “hypertrophic potential” cannot be inferred. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(1), E1–E2. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001249

- Matheus Barbalho , Victor Coswig , Daniel Souza , Julio Cerca Serrão , Mário Hebling Campos , Paulo Gentil Back Squat vs. Hip Thrust Resistance-training Programs in Well-trained Women

[ad_2]

Source link