[ad_1]

It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share five scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn why doing a variety of exercises per muscle group is better than doing just one, how hyperventilating can boost performance, how low-carb dieting lowers testosterone levels, and more.

Training a muscle group with several exercises causes more “complete” muscle growth than with just one.

Source: “Does Performing Different Resistance Exercises for the Same Muscle Group Induce Non-homogeneous Hypertrophy?” published on January 13, 2021 in the International Journal of Sports Medicine.

There’s a longstanding idea among old-school weightlifters that you should only use a handful of exercises to build muscle—primarily the squat, deadlift, and bench press, overhead press, and maybe a few variations thereof. Doing more than this is not only unnecessary but counterproductive, because it just wastes energy that could be spent doing more reps and sets of these breadwinners.

Studies don’t support this myopic stance, though, which is why I don’t recommend it.

For example, in a study conducted by scientists at Londrina State University, researchers had 22 detrained (they used to lift weights but had stopped) men train 3 times per week for 9 weeks. Each workout contained a horizontal pressing exercise, a vertical pulling exercise, a biceps exercise, a triceps exercise, a quad-dominant compound leg exercise, and a hamstring exercise.

Half the men performed the same set of exercises in each of their workouts, while the other half varied the exercises they used. For example, the first group did the flat bench press in each of their workouts, but the second group performed flat bench press on day one, incline bench press on day two, and decline bench press on day three.

The researchers measured the thickness at the top, middle, and bottom of the participants’ quads, biceps, and triceps at the beginning and end of the trial and found that overall muscle growth was similar in both groups.

However, the group that used a variety of exercises gained muscle at all of the points the researchers measured, whereas the group that stuck to the same exercises didn’t see growth in 2 of the 12 sites.

Basically, training a muscle group with only one exercise (flat bench press for your pecs, for instance) is like trying to grow a garden with half of your plants in the shade. While this can work, it’s better to give the whole plot (or muscle group) the ingredients it needs to grow.

These findings jive with results from previous studies that show that doing a couple of different exercises to train each of your major muscle groups in different ways, from different directions, and at different angles causes more balanced growth than doing just one exercise per major muscle group.

And that’s why this is the approach I advocate in my training programs Bigger Leaner Stronger for men and Thinner Leaner Stronger for women.

The Takeaway: Training each major muscle group with a variety of exercises that train your muscles in different ways, from different directions, and at different angles causes more balanced growth than doing just one exercise per major muscle group.

You gain the same amount of muscle and strength when you train far from failure as you do when you train close to failure.

Source: “Resistance Training with Different Velocity Loss Thresholds Induce Similar Changes in Strength and Hypertrophy” published on June 7, 2021 in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Another strength training shibboleth is the idea that you have to push your muscles to the brink of failure (or beyond) if you want them to grow. No pain, no gain, basically. (Failure is the point where you can’t continue moving a weight despite giving your maximum effort.)

Several studies have challenged this logic, though, showing that you actually don’t need to train that close to failure to maximize strength and muscle gains.

A salient example of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences in which 10 trained people performed the leg press and leg extension unilaterally (one leg at a time) twice per week for 9 weeks.

The participants stopped a set on one leg when one of the reps was at least 15% slower than the first rep in the set, and stopped a set with the other leg when one of the reps was at least 30% slower than the first rep in the set.

(This is a type of training known as “velocity-based training.” Since your reps tend to slow down as you fatigue, it’s a reasonable way to measure how close to failure you’re training. To make it simpler, you can think of the 15% velocity loss group as stopping their sets ~5-to-7 reps shy of failure and the 30% velocity loss group as stopping their sets ~2-to-4 reps shy of failure.)

At the beginning and end of the study, the researchers measured one-rep max strength for each leg on both exercises, isometric strength, rate of force development, and quad size.

The results showed that the participants gained about the same amount of muscle and strength in both conditions, suggesting that you can gain muscle effectively even when you leave as many as 5-to-7 reps in the tank at the end of your sets. As surprising as this may seem, it’s not the first time researchers have found this to be the case.

Despite the findings of this study, it’s probably too soon to say that we should stop all sets five or more reps shy of failure. After all, this was a small, short study that only looked at the effects of unilateral, lower-body, machine exercises on experienced weightlifters. It’s impossible to know whether we could extrapolate the findings to beginners doing free-weight, bilateral, upper-body exercises, for example.

What it does tell us, though, is that training to failure is almost certainly unnecessary for gaining muscle and strength. A better heuristic is to finish your sets when you have 1-to-3 reps left, which is also the way I personally like to train, and what’s worked well for the thousands of people who’ve read my books and followed my programs for men and women.

The Takeaway: In this study, participants who trained ~5-to-7 reps shy of failure gained the same amount of muscle and strength as participants who trained ~2-to-4 reps shy of failure.

Hyperventilating between sets boosts your performance.

Source: “Hyperventilation-Aided Recovery for Extra Repetitions on Bench Press and Leg Press” published on May 1, 2020 in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

One of the reasons your muscles burn and your performance drops during workouts is the buildup of acidic compounds in the blood, like lactate, hydrogen ions, and carbon dioxide (CO2).

Supplements such as beta-alanine can help lower the acidity of your muscles and thus boost performance, but scientists at Juntendo University wanted to see if hyperventilating while training could produce similar results.

Hyperventilation, also called overbreathing, involves taking rapid, deep breaths so that your body expels more CO2 than it creates, causing your blood levels of CO2 to drop and making your blood less acidic.

While this can cause unwanted symptoms like lightheadedness, shortness of breath, and numbness or tingling in your hands and feet, it’s harmless so long as you don’t take it too far and, according to this study, may have some benefits for weightlifters when used sparingly.

(Fun fact: In The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton, the eponymous virus can only survive in a narrow pH range, which is why a constantly crying—and hyperventilating—baby was able to survive its effects).

To test their theory, the researchers had 11 experienced male weightlifters report to the lab on 2 occasions to do identical workouts consisting of 6 sets of bench press followed by 6 sets of leg press with 80% of their one-rep max, taking each set until absolute failure, and resting 5 minutes between each set.

During the first visit, the participants intentionally hyperventilated (breathing deeply and quickly for 30 seconds) before their first, third, and fifth sets and after their sixth set of each exercise. On the second visit, they hyperventilated before their second, fourth, and sixth sets.

Before and after the workouts, the researchers took blood samples from the participants to measure their blood pH levels, and during the training sessions, the researchers had the participants wear masks that measured a variety of respiratory parameters.

The results showed that when the participants breathed normally before their sets, the speed at which they completed each rep and the number of reps they could perform in each set decreased as their workouts progressed. But when the participants hyperventilated after a set, they could perform significantly more reps in the next set and didn’t experience the normal drop in reps throughout their workout that occurs as you fatigue.

When the researchers analyzed the participants’ blood samples, they found that hyperventilating caused blood acidity to plummet after each set, which is likely why it helped the participants experience less muscular fatigue and why their performance improved compared to when they breathed normally.

You should always be wary of supposed “hacks” and “shortcuts” for accomplishing any fitness goal, but this study offers good evidence that hyperventilating is a simple, effective, and free way to boost your workout performance.

While the researchers didn’t examine this specifically, I’d also imagine that hyperventilating would be particularly effective during blood-flow restriction workouts, which cause a significant buildup of acidic byproducts in your muscles.

If you want to learn how to use hyperventilation to improve your workout performance, check out this article:

Can Hyperventilating Make You Stronger? What Science Says

The Takeaway: Hyperventilating for 30 seconds immediately before you perform a weightlifting set lowers your blood acidity and significantly boosts the number of reps you can perform.

All forms of creatine boost performance, but monohydrate is the most cost-effective.

Source: “ Efficacy of Alternative Forms of Creatine Supplementation on Improving Performance and Body Composition in Healthy Subjects” published on February 11, 2021 in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Creatine monohydrate is the most well-studied and scientifically supported sports supplement on the market.

There are many other kinds of creatine, though, including creatine citrate, creatine hydrochloride, and buffered creatine, and many supplement companies claim these forms are superior to regular ‘ol monohydrate (and charge a corresponding markup).

Are these designer creatine supplements better than monohydrate, though?

That’s what scientists at the University of Colorado wanted to find out when they performed a systematic review of 17 studies looking at the performance benefits of different forms of creatine, including magnesium-creatine chelate, creatine citrate, creatine malate, creatine ethyl ester, creatine nitrate, and creatine pyruvate.

Of the 17 studies, 7 looked at creatine’s effect on weightlifting (which we’ll focus on here because they’re the most relevant). In three of the seven studies, researchers compared creatine monohydrate and an alternative creatine against a placebo, and in the other four studies, researchers compared one or more alternative creatines against a placebo.

The results showed that alternative forms of creatine significantly enhanced performance more than placebo in four studies and that all forms of creatine (including monohydrate) enhanced performance to a similar degree.

(One curious finding worthy of mention was that in one of the reviewed studies, creatine monohydrate didn’t enhance performance more than placebo to a statistically significant degree, while creatine nitrate did. However, there wasn’t a statistically significant difference between creatine monohydrate and creatine nitrate. In other words, both creatine supplements enhanced performance to a similar degree, even if only one managed to reach statistical significance.)

In other words, you can expect similar benefits from all kinds of creatine. That said, creatine monohydrate is significantly cheaper than the other forms, so there’s no good reason to buy anything else.

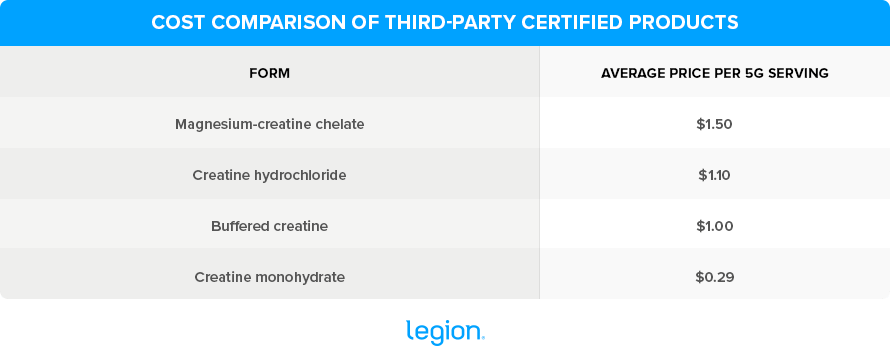

Here are the results from the researchers’ cost analysis of the alternative types of creatine that are third-party certified for sport:

As you can see, creatine monohydrate is three-to-five times more affordable than other forms of creatine, and just as effective.

And if you want a 100% natural creatine monohydrate supplement that also includes two other ingredients that will boost muscle growth and improve recovery, try Recharge.

(Or if you aren’t sure that Recharge is the right fit for your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

The Takeaway: All forms of creatine boost athletic performance to a similar degree, but creatine monohydrate is three-to-five times cheaper than other forms, making it the best option.

Low-carb, high-protein dieting decreases testosterone in healthy men.

Source: “Low-carbohydrate diets and men’s cortisol and testosterone: Systematic review and meta-analysis” published on March 7, 2022 in Nutrition and Health.

Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone, and it plays a major role in libido, bone density, muscle mass and strength, and fat distribution. As such, most men—particularly men who like to train—will do just about anything to keep their testosterone levels as high as possible, including taking “testosterone boosters,” using therapies like TRT, and following diets designed to maximize T.

This study conducted by scientists at the University of Worcester aimed to explore the latter. Specifically, they wanted to know how low-carb dieting affects testosterone in healthy adult men (the researchers also looked at how low-carb diets affect cortisol levels, but the results were a little lukewarm, so we’ll skip them in this brief roundup).

To achieve this, they performed a meta-analysis of 27 studies involving 309 participants. The studies lasted from 2 days to 8 weeks, and 95% of the participants were physically active during the trials.

The average carb intake in the low-carb diets reviewed was 12% of daily calories, and the average carb intake in the high-carb diets reviewed was 58% of daily calories. As a general rule, the low-carb diets also tended to be higher in fat, protein, and cholesterol than the high-carb diets but lower in fiber and sugar.

They found that for low-carb diets with moderate protein intake (less than 35% daily of calories), low-carb dieting didn’t significantly affect T. However, when protein intake was high (more than 35% of daily calories), low-carb dieting significantly reduced testosterone levels.

It would be easy to get carried away with these results and demonize low-carb dieting, but there are a couple of reasons that I think these results perhaps aren’t as bad as they first appear. For instance, there were only 26 participants across 3 studies that followed a low-carb, high-protein diet, and one of those studies was only 3 days long and involved an unrealistic diet protocol (5% carbs, 50% fat, and 45% protein).

What’s more, another of the studies involved only 7 participants, one of whom experienced an unusually large fluctuation in testosterone when he switched from a low-carb to a high-carb diet, which greatly impacted the final results.

On the whole, though, testosterone levels still tended to drop when people switched to low-carb diets. Thus, it’s fair to say that anyone concerned about their T levels should avoid low-carb dieting and opt for a more moderate approach instead. Here’s what I recommend in my fitness books for men and women:

- Consume 0.8-to-1 gram of protein per pound of body weight per day.

- Consume 30-to-50% of your daily calories from carbohydrates.

- Consume 20-to-30% of daily calories from fat.

And if you want specific advice about how much of each macronutrient, how many calories, and which foods you should eat to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz. In less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.

The Takeaway: Following a low-carb diet may decrease testosterone levels. If you want to do everything possible to boost your T levels, make sure you include some carbs in your diet (150 grams per day is a good minimum to shoot for).

+ Scientific References

- De Vasconcelos Costa, B. D., Kassiano, W., Nunes, J. P., Kunevaliki, G., Castro-E-Souza, P., Rodacki, A., Cyrino, L. T., Cyrino, E. S., & Fortes, L. D. S. (2021). Does Performing Different Resistance Exercises for the Same Muscle Group Induce Non-homogeneous Hypertrophy? International Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(9), 803–811. https://doi.org/10.1055/A-1308-3674

- Fonseca, R. M., Roschel, H., Tricoli, V., De Souza, E. O., Wilson, J. M., Laurentino, G. C., Aihara, A. Y., De Souzaleão, A. R., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2014). Changes in exercises are more effective than in loading schemes to improve muscle strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(11), 3085–3092. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000539

- Brandão, L., de Salles Painelli, V., Lasevicius, T., Silva-Batista, C., Brendon, H., Schoenfeld, B. J., Aihara, A. Y., Cardoso, F. N., de Almeida Peres, B., & Teixeira, E. L. (2020). Varying the Order of Combinations of Single- and Multi-Joint Exercises Differentially Affects Resistance Training Adaptations. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(5), 1254–1263. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003550

- Barakat, C., Barroso, R., Alvarez, M., Rauch, J., Miller, N., Bou-Sliman, A., & De Souza, E. O. (2019). The Effects of Varying Glenohumeral Joint Angle on Acute Volume Load, Muscle Activation, Swelling, and Echo-Intensity on the Biceps Brachii in Resistance-Trained Individuals. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 7(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS7090204

- Nobrega, S. R., Ugrinowitsch, C., Pintanel, L., Barcelos, C., & Libardi, C. A. (2018). Effect of Resistance Training to Muscle Failure vs. Volitional Interruption at High- and Low-Intensities on Muscle Mass and Strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(1), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001787

- Martorelli, S., Cadore, E. L., Izquierdo, M., Celes, R., Martorelli, A., Cleto, V. A., Alvarenga, J. G., & Bottaro, M. (2017). Strength Training with Repetitions to Failure does not Provide Additional Strength and Muscle Hypertrophy Gains in Young Women. European Journal of Translational Myology, 27(2), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.4081/EJTM.2017.6339

- Carroll, K. M., Bazyler, C. D., Bernards, J. R., Taber, C. B., Stuart, C. A., Deweese, B. H., Sato, K., & Stone, M. H. (2019). Skeletal Muscle Fiber Adaptations Following Resistance Training Using Repetition Maximums or Relative Intensity. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 7(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS7070169

- Lasevicius, T., Schoenfeld, B. J., Silva-Batista, C., de Souza Barros, T., Aihara, A. Y., Brendon, H., Longo, A. R., Tricoli, V., de Almeida Peres, B., & Teixeira, E. L. (2022). Muscle Failure Promotes Greater Muscle Hypertrophy in Low-Load but Not in High-Load Resistance Training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(2), 346–351. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003454

- Sakamoto, A., Naito, H., & Chow, C. M. (2020). Hyperventilation-Aided Recovery for Extra Repetitions on Bench Press and Leg Press. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(5), 1274–1284. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003506

- Lühker, O., Berger, M. M., Pohlmann, A., Hotz, L., Gruhlke, T., & Hochreiter, M. (2017). Changes in acid–base and ion balance during exercise in normoxia and normobaric hypoxia. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(11), 2251. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-017-3712-Z

- Ament, W., & Verkerke, G. (2009). Exercise and fatigue. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 39(5), 389–422. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200939050-00005

- Sakamoto, A., Naito, H., & Chow, C. M. (2020). Hyperventilation-Aided Recovery for Extra Repetitions on Bench Press and Leg Press. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(5), 1274–1284. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003506

- Galvan, E., Walker, D. K., Simbo, S. Y., Dalton, R., Levers, K., O’Connor, A., Goodenough, C., Barringer, N. D., Greenwood, M., Rasmussen, C., Smith, S. B., Riechman, S. E., Fluckey, J. D., Murano, P. S., Earnest, C. P., & Kreider, R. B. (2016). Acute and chronic safety and efficacy of dose dependent creatine nitrate supplementation and exercise performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-016-0124-0

- Whittaker, J., & Harris, M. (2022). Low-carbohydrate diets and men’s cortisol and testosterone: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition and Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/02601060221083079

- Langfort, J., Zarzeczny, R., Nazar, K., & Kaciuba-Uscilko, H. (2001). The effect of low-carbohydrate diet on the pattern of hormonal changes during incremental, graded exercise in young men. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 11(2), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.11.2.248

[ad_2]

Source link