[ad_1]

The dumbbell step-up is an exercise most people should be doing but aren’t.

It trains all the muscles in your lower body, helps eliminate size and strength imbalances, boosts your squat performance, and is easier on your knees and back than many other lower-body exercises.

It’s also highly functional, which means it mimics movements you do in daily life.

Why does it get such a collective yawn from fitness buffs, then?

Partly because it limits the amount of weight you can lift, so it doesn’t stroke your ego as much as other lower-body exercises. Many people also think of it as a rehab exercise, or one that’s reserved for “senior” weightlifters that can no longer squat.

Either way, pigeonholing the dumbbell step-up as a second-tier exercise is a mistake.

In this article, you’ll learn what the dumbbell step-up is, its benefits, the muscles it works, how to do it with proper form, the best dumbbell step-up alternatives, and more.

What Is a Dumbbell Step-up?

The dumbbell step-up, also known as the “dumbbell box step-up,” is a lower-body exercise that involves “stepping up” onto a knee-high box or bench while holding a dumbbell in each hand.

While it’s possible to do the step-up using your body weight or a barbell, the most common variation (and the one we’ll focus on in this article) is the dumbbell step-up.

Dumbbell Step-up: Benefits

1. It trains your entire lower body.

Several studies show that the step-up with dumbbells effectively trains your entire lower body, including your glutes, hamstrings, and quads.

In one study conducted by scientists at Marquette University, researchers found that the dumbbell step-up placed more demand on the glutes than the barbell squat (and the participants were Division 1 college athletes with an average squat one-rep max of 350 pounds).

This doesn’t mean that the dumbbell step-up is more effective for developing your glutes than the squat, though. The researchers also noted that the squat trains all of your lower-body muscles to a high degree, and it allows you to lift heavier weights, which makes it better for gaining lower-body muscle and strength overall.

What it does mean is that the dumbbell step-up is an excellent exercise in its own right and one that you can include in your program to train your glutes, quads, and hamstrings effectively.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about what exercises to include in your training program to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

2. It trains your lower body unilaterally.

The dumbbell step-up is a unilateral exercise, which means it allows you to train one side of your body at a time.

This is beneficial because it . . .

- May enable you to lift more total weight than you can with some bilateral exercises. (exercises that train both sides of the body at the same time), which may help you gain more muscle over time

- Helps you develop a greater mind-muscle connection with your quads and glutes, because you only need to focus on one side of your body at a time

- Helps you correct muscle imbalances, because both sides of your body are forced to lift the same amount of weight (one side can’t “take over” from the other)

3. It’s ideal for people with lower-back or knee problems.

Your spine isn’t under much pressure during the dumbbell step-up and you generally don’t need to use a lot of weight to reap the benefits of the exercise, which means it’s kinder to your lower-back and knees than exercises like the back squat, front squat, and Romanian deadlift.

4. It may improve your squat.

While it’s true that the best way to get better at squatting is to squat more, only squatting probably isn’t the most productive way to train.

That’s because the squat is extremely taxing on the body, and if you only ever squat to increase lower-body strength, you’ll quickly wear yourself to a frazzle and potentially increase your risk of overreaching and injury.

Research shows that the dumbbell step-up is a fantastic “accessory” exercise to the squat—it enables you to gain muscle and strength that boosts your squat performance without placing nearly as much strain on your body.

5. It’s an effective exercise for older adults.

In everyday life we’re regularly required to step onto higher surfaces (when climbing stairs, stepping onto a curb, or getting into and out of a car, for example). Age and inactivity saps our strength and coordination, which makes all of these movements more difficult and increases our risk of falling and injuring ourselves.

Step-up exercises of any kind allow you to gain or maintain the muscle and strength you need to step up onto higher surfaces, which helps older people stay independent and enjoy a better quality of life.

That’s why the dumbbell step-up is one of the exercises I recommend in my fitness book for middle-agers (and golden-agers), Muscle for Life.

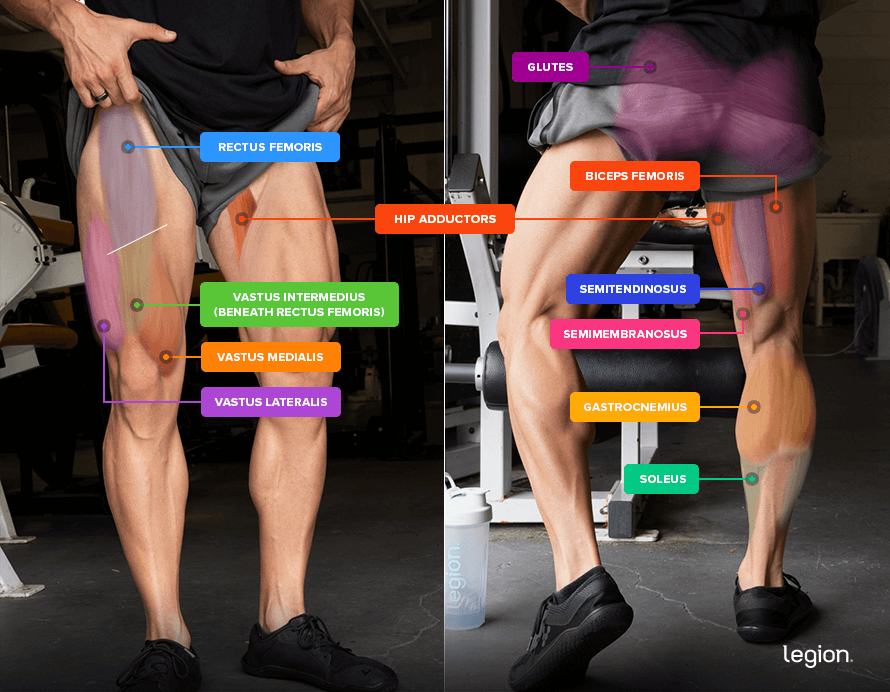

Dumbbell Step-up: Muscles Worked

The main muscles worked by the dumbbell step-up are the . . .

Here’s what these muscles look like on your body:

How to Do the Dumbbell Step-up With Proper Form

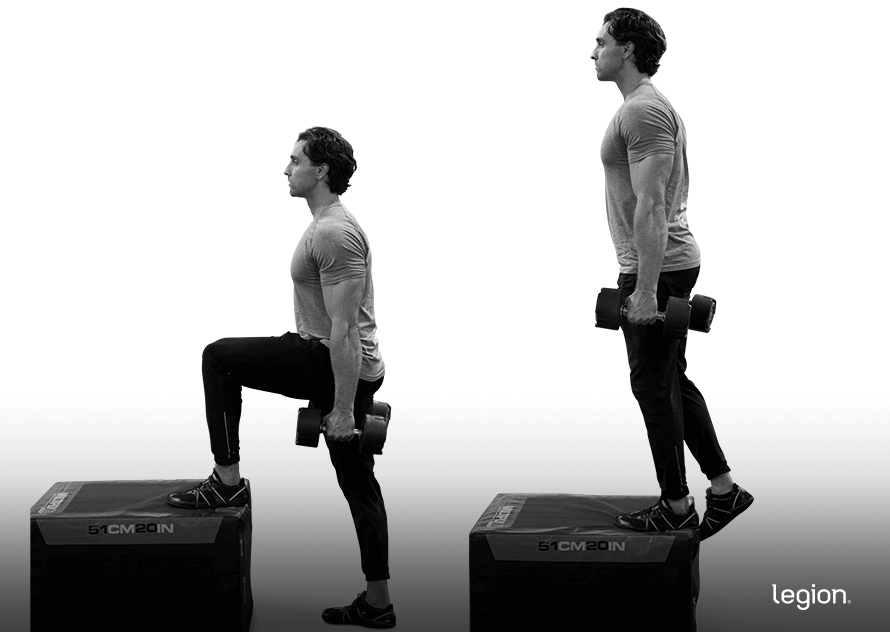

The best way to learn how to do the dumbbell step-up with proper form is to split the exercise into three parts: set up, step up, and descend.

Step 1: Set Up

While holding a dumbbell in each hand, stand 8-to-12 inches in front of a box, bench, or other stable surface that’s about knee-height. Allow your arms to hang at your sides, keep your chest up, then step your left foot onto the box.

Step 2: Step Up

Keeping your weight on your left foot, push through your left heel to fully straighten your left leg. Don’t swing your arms or lean too far forward—this creates momentum and makes the exercise easier and thus less effective.

Step 3: Descend

While keeping your chest up and your arms at your sides, lower your right foot toward the floor and return to the starting position. This is a mirror image of what you did during the step up.

Don’t let your body fall back to the starting position or try to lower yourself slowly—the entire descent should be controlled but only take about a second.

Once you’ve completed the desired number of reps, switch sides and repeat the process with your right leg.

Dumbbell Step-up: Alternatives

Here are three of the best alternatives to the dumbbell step up.

1. Dumbbell High Step-up

The only difference between the regular dumbbell step-up and the dumbbell high step-up is the height of the box you use. In the regular dumbbell step-up, the box is about knee-height off the floor, whereas in the dumbbell high step-up, the box is about the height of your midthigh.

By using a taller box, you increase the range of motion of the exercise and train your glutes and quads in a more stretched position, which is generally better for muscle growth.

However, the dumbbell high step-up is significantly more challenging than the regular dumbbell step-up and requires more full-body coordination and mobility, so it may not be suitable if you’re new to weightlifting.

2. Dumbbell Lateral Step-up

By stepping onto a box laterally (sideways) rather than forwards, you increase the amount of work your glutes do, making the dumbbell lateral step-up a good step-up variation for people looking to maximize glute growth.

That said, the dumbbell lateral step-up also requires more balance and coordination than the regular step-up, which limits the amount of weight you can lift, and thus its muscle- and strength-building potential.

3. Dumbbell Goblet Step-up

In the dumbbell goblet step-up, you hold the weight in front of your chest rather than by your sides. This makes the dumbbell goblet step-up slightly easier on your grip, but more taxing on your upper back.

+ Scientific References

- Simenz, C. J., Garceau, L. R., Lutsch, B. N., Suchomel, T. J., & Ebben, W. P. (2012). Electromyographical analysis of lower extremity muscle activation during variations of the loaded step-up exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(12), 3398–3405. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3182472FAD

- Selseth, A., Dayton, M., Cordova, M. L., Ingersoll, C. D., & Merrick, M. A. (2000). Quadriceps Concentric EMG Activity Is Greater than Eccentric EMG Activity during the Lateral Step-Up Exercise. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 9(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSR.9.2.124

- (PDF) Gluteus Maximus Activation during Common Strength and Hypertrophy Exercises: A Systematic Review. (n.d.). Retrieved May 23, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339302672_Gluteus_Maximus_Activation_during_Common_Strength_and_Hypertrophy_Exercises_A_Systematic_Review

- Kipp, K., Kim, H., & Wolf, W. I. (2022). Muscle Forces During the Squat, Split Squat, and Step-Up Across a Range of External Loads in College-Aged Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(2), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003688

- Jakobi, J. M., & Chilibeck, P. D. (2001). Bilateral and unilateral contractions: possible differences in maximal voluntary force. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology = Revue Canadienne de Physiologie Appliquee, 26(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1139/H01-002

- Janzen, C. L., Chilibeck, P. D., & Davison, K. S. (2006). The effect of unilateral and bilateral strength training on the bilateral deficit and lean tissue mass in post-menopausal women. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2006 97:3, 97(3), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-006-0165-1

- Gamble, P. P. C. (n.d.). Implications and Applications of Training Specificity for Co… : Strength & Conditioning Journal. Retrieved May 23, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Abstract/2006/06000/Implications_and_Applications_of_Training.9.aspx

- Appleby, B. B., Cormack, S. J., & Newton, R. U. (2019). Specificity and transfer of lower-body strength: Influence of bilateral or unilateral lower-body resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33(2), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002923

- Rodrigues, F., Domingos, C., Monteiro, D., & Morouço, P. (2022). A Review on Aging, Sarcopenia, Falls, and Resistance Training in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19020874

- Wang, M. Y., Flanagan, S., Song, J. E., Greendale, G. A., & Salem, G. J. (2003). Lower-extremity biomechanics during forward and lateral stepping activities in older adults. Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol, Avon), 18(3), 214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(02)00204-8

- Schoenfeld, B. J., & Grgic, J. (2020). Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 205031212090155. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120901559

- Oranchuk, D. J., Storey, A. G., Nelson, A. R., & Cronin, J. B. (2019). Isometric training and long-term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 29(4), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/SMS.13375

- Mercer, V. S., Gross, M. T., Sharma, S., & Weeks, E. (2009). Comparison of Gluteus Medius Muscle Electromyographic Activity During Forward and Lateral Step-up Exercises in Older Adults. Physical Therapy, 89(11), 1205–1214. https://doi.org/10.2522/PTJ.20080229

[ad_2]

Source link