[ad_1]

The term adrenal fatigue was coined in the early aughts by chiropractor and naturopathic doctor James Wilson to describe a syndrome that people supposedly suffer in response to prolonged stress.

According to him, living with long-term stress puts undue strain on your adrenals, the glands that sit atop your kidneys and secrete hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline.

Over time, this strain fatigues your adrenals and stops them from functioning as they should, causing your body to weary and your health to nosedive.

While this sounds like a plausible theory, it’s highly controversial in the medical world, primarily because there’s no scientific evidence it exists.

In this article, we’re going to look at the broader body of research on adrenal function and fatigue to fathom whether the theory of adrenal fatigue is worthy of merit or mockery.

What Is Adrenal Fatigue?

Adrenal fatigue, or adrenal fatigue syndrome, refers to a set of symptoms that purportedly occur in people under long-term mental, physical, or emotional stress.

Medical doctors don’t classify adrenal fatigue as a bona fide medical condition. Thus, you can only receive a diagnosis from a holistic or functional health practitioner.

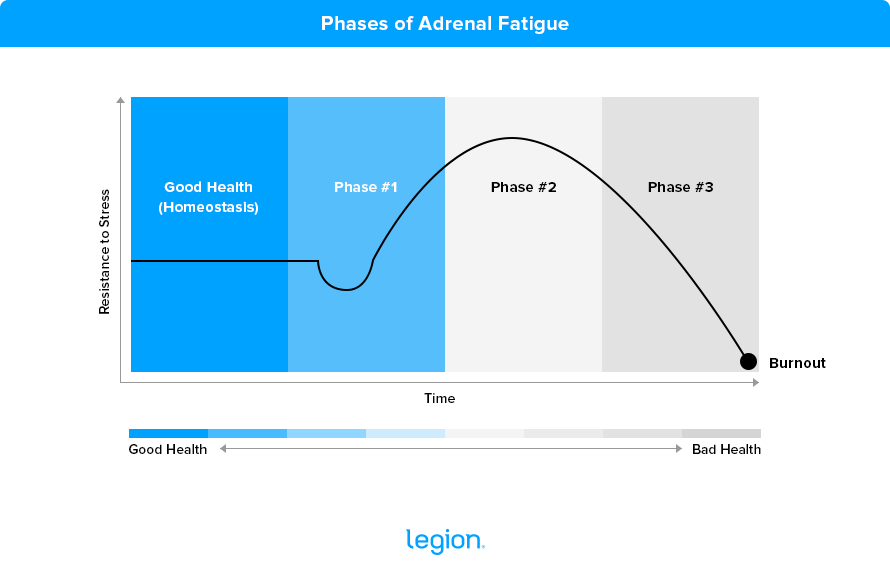

The theory behind adrenal fatigue is based on Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome, which describes three phases your body goes through in response to long-term stress. Here’s how health practitioners typically characterize each stage in the context of adrenal fatigue:

- Phase #1: The first phase of adrenal fatigue (sometimes called the “alarm reaction” phase) occurs in response to a stressful situation and may last days or weeks. At this time, your adrenal glands release cortisol (the body’s main stress hormone) and adrenaline, triggering the “fight-or-flight response.” If the source of stress persists, you progress to Phase #2.

- Phase #2: During Phase #2 (which some practitioners call the “resistance response” phase), your adrenal glands begin to fatigue as they struggle to keep up with the body’s demand for cortisol. This causes cortisol levels to dip, which brings about several adverse side effects. If you fail to lower your stress levels and allow Phase #2 to continue for too long, you enter Phase #3.

- Phase #3: In Phase #3 (also known as the “adrenal exhaustion” phase), your adrenal glands become exhausted, causing cortisol levels to sink. According to those who believe in adrenal fatigue, this saps sufferers of numerous hormones, vitamins, and nutrients and hinders several metabolic processes.

Here’s a graph that shows how your resistance to stress changes as you progress through each phase. As you can see, the more your adrenals fatigue, the less you’re able to cope with stress, and the worse your health supposedly becomes:

What Are the Symptoms of Adrenal Fatigue?

These are the most commonly reported adrenal fatigue symptoms by phase:

- Phase #1: Most people say noticeable symptoms are rare, though some claim to experience experience high blood pressure and heart rate.

- Phase #2: Some people report more fatigue than usual at the end of the day and feel less well-rested in the morning. Some people feel anxious, irritable, and sluggish, while others report gaining weight despite maintaining their regular diet and exercise regimen.

- Phase #3: People generally claim that the symptoms from Phase #2 worsen in Phase #3, and that they also encounter more issues with allergies and asthma, compromised immune function, autoimmune diseases, gastrointestinal distress, food intolerances, infertility, low sex drive, depression, weight gain, muscle loss, joint pain, “brain fog,” apathy, lightheadedness, cravings for salt and sugar, osteoporosis, skin conditions, and insomnia.

According to some proponents of adrenal fatigue, your risk of “cardiovascular collapse and death” also dramatically increases when you encounter “burnout” (which some count as “Phase #4”).

Is Adrenal Fatigue Real?

Despite what many alternative health practitioners say, there’s little evidence that adrenal fatigue exists. There are strong indications that it doesn’t, though.

For example, one of the central tenets of the theory behind adrenal fatigue is that chronic (long-term) stress frazzles your adrenal glands, causing your cortisol levels to bottom out and triggering a raft of undesirable and potentially life-threatening symptoms.

However, most research shows that people suffering from chronic work-related stress tend to have higher cortisol levels than healthy people in the morning and that both groups have similar cortisol levels throughout the remainder of the day.

It’s a similar story among athletes following rigorous training regimens.

In one meta-analysis, researchers found that in most cases, overtrained and healthy athletes have similar cortisol levels, and both groups’ levels are within a healthy range.

Furthermore, research shows that people suffering from chronic pain or illnesses such as metabolic syndrome, heart disease, depression, fibromyalgia, Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder typically have higher or similar cortisol levels compared to healthy people despite dealing with more daily physical and mental stress.

Research investigating the link between cortisol and chronic fatigue offers interesting insight, too.

If cortisol levels and fatigue were linked as adrenal fatigue advocates suggest, you’d expect to see clear trends in the scientific literature.

Specifically, you’d expect most (if not all) participants in chronic fatigue studies to have low cortisol levels. You’d also expect to find a reliable relationship between their cortisol levels and the severity of their symptoms so that those with the worst symptoms have the lowest cortisol levels.

However, this simply isn’t the case—most research shows that chronically fatigued people have similar or higher cortisol levels compared to healthy people. Some studies show that fatigued folk have lower cortisol, but these tend to be the exception rather than the rule.

There doesn’t appear to be a reliable relationship between cortisol levels and the severity of symptoms, either. Nor is it always the case that symptoms improve as cortisol rises.

If the above weren’t enough to convince you that adrenal fatigue is fictitious, this should be the clincher: despite their best efforts, scientists can’t find any evidence adrenal fatigue exists, or any link between dysfunctional adrenal glands and fatigue.

For instance, in a meta-analysis conducted by scientists at the Federal University of São Paulo, researchers reviewed 58 studies to see if there was any association between adrenal impairment and fatigue.

As they scrutinized the data, the researchers discovered that shoddy assessment techniques, “unsubstantiated methodology,” false premises, incoherent research directions, and inappropriate and invalid conclusions permeated most of the research. What’s more, they found no consistency in the results.

In other words, the best research that you can draw on to support adrenal fatigue is ineptly conducted, illogical, and contradictory.

This, they felt, made it impossible to substantiate claims that adrenal fatigue exists, leading them to conclude that adrenal fatigue is “a myth” (a motion the US Endocrine Society seconds).

Conclusion

There’s no evidence, direct or otherwise, that your adrenal glands fatigue over time. Nor is there reason to believe that chronically stressed people have rock-bottom cortisol levels and that their diminished hormone profile is responsible for their symptoms.

Thus, it’s fair to conclude that adrenal fatigue doesn’t exist.

If you are suffering symptoms that others claim are related to tuckered out adrenals, and you haven’t been able to figure out the cause or a potential solution, your best course of action is to a) lift weights, get plenty of sleep, and following a good diet, and if you’re already doing those things, speak to a medical professional.

FAQ #1: What’s the best adrenal fatigue treatment?

Adrenal fatigue doesn’t exist and, thus, can’t be treated.

If you have symptoms such as extreme tiredness, weakness, depression, unexplained weight gain, joint pain, and so on, it’s important to seek medical advice rather than waste time accepting an unproven diagnosis such as adrenal fatigue.

FAQ #2: What are the best adrenal fatigue supplements?

Many holistic health practitioners sell adrenal fatigue supplements, including ashwagandha, rhodiola rosea, licorice root, ginseng, schizandra, and maca, that they claim will help treat your symptoms.

Adrenal fatigue isn’t a real medical condition, though, so these supplements won’t alleviate it (although some of them, like ashwagandha, rhodiola rosea, and maca may offer other benefits).

A better solution is to speak to a medical doctor who can advise you on the best course of treatment.

FAQ #3: How do you reverse adrenal fatigue?

Holistic health practitioners will tell you that you can reverse adrenal fatigue by following their exercise, supplement, and wellness programs, but this is bunk.

Adrenal fatigue doesn’t exist, which means there’s no way to reverse it.

If you’re experiencing symptoms associated with adrenal fatigue, speak to your doctor. They should be able to offer you medically sound advice about the best course of treatment.

+ Scientific References

- Schulz PhD, P., Kirschbaum PhD, C., Prüßner MS, J., & Hellhammer PhD, D. (n.d.). Increased free cortisol secretion after awakening in chronically stressed individuals due to work overload – Schulz – 1998 – Stress Medicine – Wiley Online Library. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1700(199804)14:2%3C91::AID-SMI765%3E3.0.CO;2-S

- Wüst, S., Federenko, I., Hellhammer, D. H., & Kirschbaum, C. (2000). Genetic factors, perceived chronic stress, and the free cortisol response to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 25(7), 707–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00021-4

- Ockenfels, M. C. M., Porter, L. M., Smyth, J. M., Kirschbaum, C. P., Hellhammer, D. H. P., & Stone, A. A. P. (n.d.). Effect of Chronic Stress Associated With Unemployment on Sal… : Psychosomatic Medicine. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Abstract/1995/09000/Effect_of_Chronic_Stress_Associated_With.8.aspx

- Alderling, M., Theorell, T., De La Torre, B., & Lundberg, I. (2006). The demand control model and circadian saliva cortisol variations in a Swedish population based sample (The PART study). BMC Public Health, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-288/FIGURES/1

- Cadegiani, F. A., & Kater, C. E. (2017). Hormonal aspects of overtraining syndrome: a systematic review. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S13102-017-0079-8

- Riva, R., Mork, P. J., Westgaard, R. H., & Lundberg, U. (2012). Comparison of the cortisol awakening response in women with shoulder and neck pain and women with fibromyalgia. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(2), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2011.06.014

- Van Uum, S. H. M., Sauvé, B., Fraser, L. A., Morley-Forster, P., Paul, T. L., & Koren, G. (2009). Elevated content of cortisol in hair of patients with severe chronic pain: A novel biomarker for stress. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/10253890801887388, 11(6), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890801887388

- Brunner, E. J., Hemingway, H., Walker, B. R., Page, M., Clarke, P., Juneja, M., Shipley, M. J., Kumari, M., Andrew, R., Seckl, J. R., Papadopoulos, A., Checkley, S., Rumley, A., Lowe, G. D. O., Stansfeld, S. A., & Marmot, M. G. (2002). Adrenocortical, autonomic, and inflammatory causes of the metabolic syndrome: nested case-control study. Circulation, 106(21), 2659–2665. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000038364.26310.BD

- Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2009). Cortisol awakening response and psychosocial factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biological Psychology, 80(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPSYCHO.2008.10.004

- Blackburn-Munro, G., & Blackburn-Munro, R. E. (2001). Chronic Pain, Chronic Stress and Depression: Coincidence or Consequence? Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 13(12), 1009–1023. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.0007-1331.2001.00727.X

- Fatima, G., Das, S. K., Mahdi, A. A., Verma, N. S., Khan, F. H., Tiwari, A. M. K., Jafer, T., & Anjum, B. (2012). Circadian Rhythm of Serum Cortisol in Female Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry 2012 28:2, 28(2), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12291-012-0258-Z

- Agha-Hosseini, F., Shirzad, N., & Moosavi, M. S. (2016). The association of elevated plasma cortisol and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, a neglected part of immune response. Acta Clinica Belgica, 71(2), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2015.1116152

- Girshkin, L., Matheson, S. L., Shepherd, A. M., & Green, M. J. (2014). Morning cortisol levels in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 49(1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2014.07.013

- Scott, L. V., Burnett, F., Medbak, S., & Dinan, T. G. (1998). Naloxone-mediated activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychological Medicine, 28(2), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291797006260

- L N Yatham, R L Morehouse, B T Chisholm, D A Haase, D D MacDonald, & T J Marrie. (n.d.). Neuroendocrine assessment of serotonin (5-HT) function in chronic fatigue syndrome – PubMed. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7788624/

- Dinan, T. G., Majeed, T., Lavelle, E., Scott, L. V., Berti, C., & Behan, P. (1997). Blunted serotonin-mediated activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 22(4), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(97)00002-4

- MacHale, S. M., Cavanagh, J. T. O., Bennie, J., Carroll, S., Goodwin, G. M., & Lawrie, S. M. (1998). Diurnal variation of adrenocortical activity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuropsychobiology, 38(4), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1159/000026543

- Tomic, S., Brkic, S., Lendak, D., Maric, D., Medic Stojanoska, M., & Novakov Mikic, A. (2017). Neuroendocrine disorder in chronic fatigue syndrome. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 47(4), 1097–1103. https://doi.org/10.3906/SAG-1601-110

- Sjörs, A., Ljung, T., & Jonsdottir, I. H. (2012). Long-term follow-up of cortisol awakening response in patients treated for stress-related exhaustion. BMJ Open, 2(4), e001091. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2012-001091

- Rahman, K., Burton, A., Galbraith, S., Lloyd, A., & Vollmer-Conna, U. (2011). Sleep-Wake Behavior in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Sleep, 34(5), 671. https://doi.org/10.1093/SLEEP/34.5.671

- Blockmans, D., Persoons, P., Van Houdenhove, B., Lejeune, M., & Bobbaers, H. (2003). Combination therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone does not improve symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. American Journal of Medicine, 114(9), 736–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00182-7

- Grossi, G., Perski, A., Evengård, B., Blomkvist, V., & Orth-Gomér, K. (2003). Physiological correlates of burnout among women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55(4), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00633-5

- Tao, N., Zhang, J., Song, Z., Tang, J., & Liu, J. (2015). Relationship Between Job Burnout and Neuroendocrine Indicators in Soldiers in the Xinjiang Arid Desert: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(12), 15154. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH121214977

- Melamed, S., Ugarten, U., Shirom, A., Kahana, L., Lerman, Y., & Froom, P. (1999). Chronic burnout, somatic arousal and elevated salivary cortisol levels. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46(6), 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00007-0

- Bearn, J., Allain, T., Coskeran, P., Munro, N., Butler, J., McGregor, A., & Wessely, S. (1995). Neuroendocrine responses to d-fenfluramine and insulin-induced hypoglycemia in chronic fatigue syndrome. Biological Psychiatry, 37(4), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(94)00121-I

- Strickland, P., Morriss, R., Wearden, A., & Deakin, B. (1998). A comparison of salivary cortisol in chronic fatigue syndrome, community depression and healthy controls. Journal of Affective Disorders, 47(1–3), 191–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00134-1

- Scott, L. V., & Dinan, T. G. (1998). Urinary free cortisol excretion in chronic fatigue syndrome, major depression and in healthy volunteers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 47(1–3), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00101-8

- Pruessner, J. C. P., Hellhammer, D. H. P., & Kirschbaum, C. P. (n.d.). Burnout, Perceived Stress, and Cortisol Responses to Awakeni… : Psychosomatic Medicine. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Abstract/1999/03000/Burnout,_Perceived_Stress,_and_Cortisol_Responses.12.aspx

- Moch, S. L., Panz, V. R., Joffe, B. I., Havlik, I., & Moch, J. D. (2003). Longitudinal changes in pituitary-adrenal hormones in South African women with burnout. Endocrine, 21(3), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1385/ENDO:21:3:267

- Blockmans, D., Persoons, P., Van Houdenhove, B., Lejeune, M., & Bobbaers, H. (2003). Combination therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone does not improve symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. American Journal of Medicine, 114(9), 736–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00182-7

- Mommersteeg, P. M. C., Heijnen, C. J., Keijsers, G. P. J., Verbraak, M. J. P. M., & Van Doornen, L. J. P. (2006). Cortisol deviations in people with burnout before and after psychotherapy: a pilot study. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 25(2), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.243

- Mommersteeg, P. M. C., Heijnen, C. J., Verbraak, M. J. P. M., & van Doornen, L. J. P. (2006). A longitudinal study on cortisol and complaint reduction in burnout. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31(7), 793–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2006.03.003

- Rodrigues Oliveira, F., Visnardi Gonçalves, L. C., Rocha Ventura da Silva, L. G., Elise Gomes, A., Trevisan, G., de Souza, A. L., Grassi-Kassisse, D. M., & Xavier de Oliveira Crege, D. R. (2015). Evaluation of massage therapy program on cortisol, serotonin levels, pain, perceived stress and quality of life in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Physiotherapy, 101, e1666–e1667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.065

- Olsson, E. M. G., Von Schéele, B., & Panossian, A. G. (2009). A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Study of the Standardised Extract SHR-5 of the Roots of Rhodiola rosea in the Treatment of Subjects with Stress-Related Fatigue. Planta Medica, 75(02), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0028-1088346

- Cadegiani, F. A., & Kater, C. E. (2016). Adrenal fatigue does not exist: a systematic review. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12902-016-0128-4

- Irina Bancos, M. D., Melanie Schorr Haines, M. D., & Jason Wexler, M. D. (n.d.). Adrenal Fatigue | Endocrine Society. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://www.endocrine.org/patient-engagement/endocrine-library/adrenal-fatigue

[ad_2]

Source link