[ad_1]

It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn the best way to train all three heads of your delts, a common problem that stops many people from building muscle, and whether weightlifting makes you smarter.

Is the behind-the-neck press the answer to well-developed delts?

Source: “Front vs Back and Barbell vs Machine Overhead Press: An Electromyographic Analysis and Implications For Resistance Training” published on July 22, 2022 in Frontiers in Physiology.

If you want to maximize your upper-body aesthetics, you need round, proportional shoulders.

And the overhead press is one of the best exercises for building your shoulders … at least part of your shoulders.

The problem is that when your shoulder training mainly consists of overhead pressing, your “front delts” will develop nicely, but your side and rear delts may lag a little.

This begs the question: is there a better way to press that trains train all three heads of the delts more uniformly?

Scientists at the University of Milan endeavored to find out with this study.

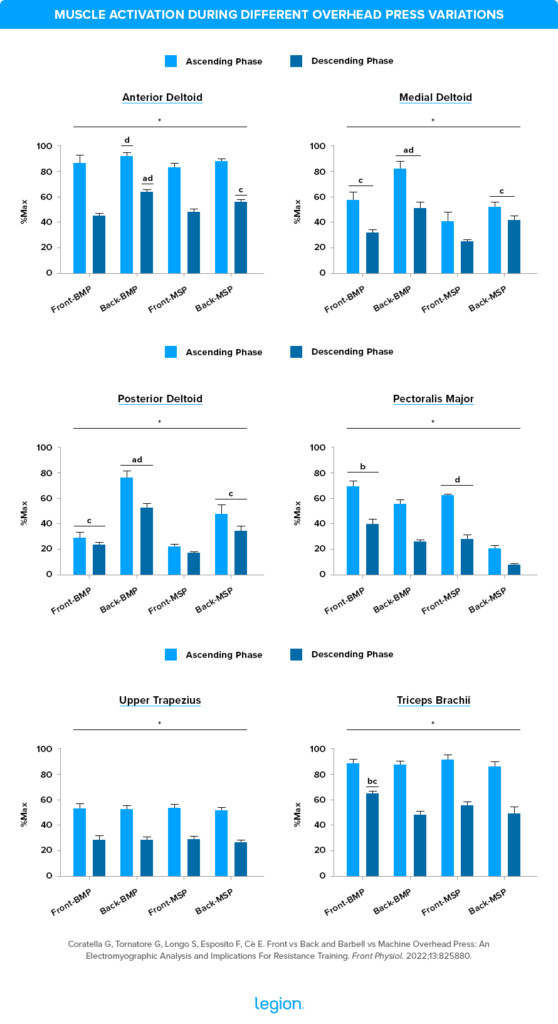

They had eight competitive male bodybuilders do one set each of the seated barbell overhead press, seated behind-the-neck barbell press, seated machine overhead press, and seated machine behind-the-neck press. During each exercise, the researchers measured muscle activation in each head of the delts and the pecs, traps, and triceps.

The results showed that the traps and triceps were similarly active regardless of exercise and that the pecs were slightly more active during the overhead press variations than the behind-the-neck press variations.

Regarding shoulder activation, the front delts were similarly active during all exercises, but the side and rear delts were significantly more active during the behind-the-neck barbell press than in the other exercises.

Here are these results in graph form:

At first reading, many people will take this to mean the behind-the-neck press is superior to the overhead press for developing your shoulders, but I’m not convinced for a few reasons.

First, most people find the behind-the-neck press uncomfortable because it demands a degree of shoulder mobility that the majority of people lack. Even for those with adequate shoulder mobility, it usually requires that you jut your head forward to avoid knocking your noggin, making it an awkward position to press from.

Second, to perform the behind-the-neck press, you have to put your shoulders into the so-called “high-five” position (upper arm out to the side with your elbow bent at 90 degrees and your palm facing forward). Research shows that this position is inherently less stable for your shoulders than when you bring your elbows forward, which increases your risk of shoulder injury.

And third, to compensate for the uncomfortable pressing position and increased injury risk, the behind-the-neck press forces you to use lighter weights than you can ordinarily press, limiting the exercise’s muscle- and strength-building potential.

By my lights, a better approach to building proportional shoulders is to make the overhead press (seated, standing, or both) the focus of your shoulder training. It allows you to train your shoulders (and several other upper-body muscle groups) with heavy weights safely and progress regularly, making it ideal for gaining muscle and strength, and is comfortable for most people.

Then round out your shoulder development with isolation exercises for the side and rear delts, such as the cable and dumbbell side lateral raise, dumbbell rear lateral raise, barbell rear delt row, and machine reverse fly.

Or, if you have limited time to train and want to maximize your shoulder development with one exercise, I’d choose the dumbbell shoulder press. This variation allows you to adopt a similar position to the behind-the-neck press, which should train your side and rear delts more than barbell pressing. However, because you use dumbbells, your arms and shoulders can move more freely, allowing you to find a safe, stable, and comfortable position.

This is how I personally like to organize my training, and it’s similar to the method I advocate in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about how you should organize your training to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: The behind-the-neck press may train your side and rear delts more than the overhead press, but it forces you into an uncomfortable and compromised position, limiting its muscle- and strength-building potential.

Lifting weights but not building muscle? You’re probably not training hard enough.

Source: “Are Trainees Lifting Heavy Enough? Self-Selected Loads in Resistance Exercise: A Scoping Review and Exploratory Meta-Analysis” published on July 5, 2022 in Sports Medicine (Auckland N.Z.).

Many weightlifters feel like they bust a gut in the gym but don’t see the progress they believe they deserve.

If this is the case for you, a recent meta-analysis conducted by scientists at Solent University might explain why.

The researchers parsed the scientific literature and found 18 suitable studies examining how hard people habitually train.

In most of these studies, the researchers asked people to perform 3 sets of 10 reps of an exercise (a couple used lower rep ranges or asked the weightlifters to do as many sets and reps as they wanted).

However, before doing the exercise, the researchers asked the people to self-select the weight they were going to use. The only stipulation was that the people had to choose a weight that would make the sets challenging.

For example, in one study, the researchers asked weightlifters to select weights that they thought would make doing 3 sets of 10 reps of the bench press, leg press, and biceps curl difficult.

The results showed that when most people are left to their own devices, they select a weight that’s equal to ~53% of their one-rep max for a set of 10 reps (bear in mind that most people can perform 10 reps of an exercise with ~75% of their one-rep max). This held true regardless of experience, age, sex, the timing of the one-rep max test, and the muscle group being trained.

The researchers also found that when people performed multiple sets, they tended to choose slightly heavier weights set-to-set and that they tended to select marginally heavier weights when doing lower-rep sets.

When the scientists scrutinized the data further, they found that people typically used progressively heavier weights over time when they trained in lower rep ranges (<10 reps per set) but progressed more cautiously when they trained in higher rep ranges (>10 reps per set). They also noticed that when people select their rep targets, they generally leave 6-to-7 reps in reserve at the end of each set. This was particularly true during high-rep training.

In other words, most people probably don’t lift heavy enough weights to maximize their progress in the gym.

You don’t have to train all the way to failure to build muscle—stopping 1-to-3 reps shy is usually sufficient. These results show, however, that when most people do sets of 10 reps, they leave ~10 reps in the tank, which means they don’t push themselves nearly hard enough if their goal is to build muscle.

How can you avoid sandbagging your workouts?

First, aim to end all your sets 1-to-3 reps shy of failure. To ensure you’re doing that, ask yourself this question at the end of each set, just before re-racking the weight: “If I absolutely had to, how many more reps could I get with good form?”

If the answer is more than two, increase the weight or reps to make your next set more challenging. If the answer is one or zero, reduce the weight or reps to make your next set less challenging.

Once you’re satisfied that you’re training close enough to failure, ensure you continue progressing by implementing double progression. Do this by increasing the weight you use for an exercise once you hit the top of your rep range for one set.

TL:DR: Most people select weights that are too light and do too few reps to maximize muscle growth. Don’t make the same mistake.

Weightlifting may make you smarter.

Source: “Effects of Acute Resistance Exercise on Executive Function: A Systematic Review of the Moderating Role of Intensity and Executive Function Domain” published on December 8, 2022 in Sports Medicine.

The most obvious benefit of exercise is that it improves your physical health, but more and more research shows it’s also good for your brain health.

Specifically, there’s a growing body of evidence that it improves executive function (EF), which refers to a group of mental skills that enable you to control your thoughts, emotions, attention, and behaviors.

EF has three core domains:

- Inhibitory control, which is your ability to make decisions without tendencies or external distractions affecting your judgment.

- Working memory, which is your ability to store or update previously stored information in response to the demands of the task you’re doing.

- Cognitive flexibility, which is your ability to use inhibitory control and working memory to alter your perspective and approach to a situation.

Using these skills adeptly helps you build strong relationships, excel academically and professionally, and avoid mental and physical decline as you age. In other words, boosting EF is one way to improve your quality of life dramatically.

To further our understanding of how weightlifting affects EF and try to puzzle out how hard you need to train to boost EF, researchers at National Taiwan Normal University conducted a systematic review of 19 studies investigating 42 separate “outcomes” (the research measured a total of 42 different data points, basically).

Overall, weightlifting positively affected EF for 57% of the outcomes measured, ~43% showed it didn’t affect EF, and no studies showed it had a detrimental effect on EF.

In terms of intensity, moderate-intensity weightlifting benefitted EF most consistently (~72% of the outcomes studied showed a positive effect), followed by low-intensity ~(57%), then high-intensity weightlifting (~41%).

Weightlifting boosted inhibitory control most regularly (~65% of the outcomes studied showed a positive effect). Comparatively, ~44% and 50% of the studies reported positive results on working memory and cognitive flexibility, respectively.

In other words, the results showed that weightlifting probably benefits EF (especially inhibitory control), and moderate-intensity weightlifting likely confers the most benefits.

This might make you think you need to take a moderate approach to weightlifting if you want to boost brain power (no “pump training” or low-rep sets, for example), but I doubt that’s the case.

In a 2019 meta-analysis conducted by scientists at Goethe University Frankfurt, researchers again found that weightlifting positively affects EF, though they found that low- and high-intensity training was the most effective and moderate-intensity weightlifting was bootless in this regard.

The difference between these studies was that each measured weightlifting’s effect on EF differently—they included different types of studies, used different testing methods and time scales, and so forth.

With that in mind, all types of weightlifting seem likely to benefit EF. If a study suggests otherwise, it’s probably more of a reflection on how the researchers designed their analysis rather than a knock on any one type of training.

Another important point when interpreting these results is that they refer to the “acute” effects of weightlifting on EF. That is, they show that weightlifting boosts cognitive function shortly after training, not that it improves EF long term.

Thus, if you want to harness the brain-boosting benefits of weightlifting, it makes sense to schedule your workouts in the morning, before work or class, or shortly before you do something that requires your full attention (an exam or an important meeting, for example). Though it stands to reason exercise would also boost long-term brain function, this isn’t as well established.

TL;DR: Weightlifting likely improves executive function for a short while after training.

+ Scientific References

- Coratella, G., Tornatore, G., Longo, S., Esposito, F., & Cè, E. (2022). Front vs Back and Barbell vs Machine Overhead Press: An Electromyographic Analysis and Implications For Resistance Training. Frontiers in Physiology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2022.825880

- Kolber, M. J., Beekhuizen, K. S., Cheng, M. S. S., & Hellman, M. A. (2010). Shoulder injuries attributed to resistance training: A brief review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(6), 1696–1704. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181DC4330

- Kolber, M. J., Corrao, M., & Hanney, W. J. (2013). Characteristics of anterior shoulder instability and hyperlaxity in the weight-training population. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(5), 1333–1339. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318269F776

- Steele, J., Malleron, T., Har-Nir, I., Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Wolf, M., Fisher, J. P., & Halperin, I. (2022). Are Trainees Lifting Heavy Enough? Self-Selected Loads in Resistance Exercise: A Scoping Review and Exploratory Meta-analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 52(12), 2909–2923. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-022-01717-9

- Alves, R. C., Prestes, J., Souza-Junior, T. P., & Follador, L. (n.d.). (PDF) Acute Effect of Weight Training at a Self-Selected Intensity on Affective Responses in Obese Adolescents. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270506207_Acute_Effect_of_Weight_Training_at_a_Self-Selected_Intensity_on_Affective_Responses_in_Obese_Adolescents

- TY, H., FT, C., RH, L., CH, H., TL, C., CH, C., TM, H., & YK, C. (2022). Effects of Acute Resistance Exercise on Executive Function: A Systematic Review of the Moderating Role of Intensity and Executive Function Domain. Sports Medicine – Open, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S40798-022-00527-7

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive Functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV-PSYCH-113011-143750

- Zelazo, P. D. (2015). Executive function: Reflection, iterative reprocessing, complexity, and the developing brain. Developmental Review, 38, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DR.2015.07.001

- Reimann, Z., Miller, J. R., Dahle, K. M., Hooper, A. P., Young, A. M., Goates, M. C., Magnusson, B. M., & Crandall, A. A. (2020). Executive functions and health behaviors associated with the leading causes of death in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(2), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318800829

- Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONT/37.4.433

- TY, H., FT, C., RH, L., CH, H., TL, C., CH, C., TM, H., & YK, C. (2022). Effects of Acute Resistance Exercise on Executive Function: A Systematic Review of the Moderating Role of Intensity and Executive Function Domain. Sports Medicine – Open, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S40798-022-00527-7

- Wilke, J., Giesche, F., Klier, K., Vogt, L., Herrmann, E., & Banzer, W. (2019). Acute Effects of Resistance Exercise on Cognitive Function in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review with Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 49(6), 905–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-019-01085-X

[ad_2]

Source link