[ad_1]

It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn how listening to music affects athletic performance, how to minimize urinary incontinence (peeing yourself) while weightlifting, and if late-night eating really makes you gain weight.

Listening to music boosts athletic performance and makes your workouts more enjoyable.

Source: “Let’s Go: Psychological, psychophysical, and physiological effects of music during sprint interval exercise” published on June 2, 2019 in Psychology of Sport & Exercise.

Most people listen to music while working out.

It makes working out more enjoyable. It pushes you to work harder. And most importantly, it drowns out the god awful music most gyms play.

That said, some folks believe listening to music can also undermine your performance by distracting you from your workout.

Is there any truth to this?

That’s what scientists at the University of British Columbia wanted to test in this study.

They had 24 untrained people do 3 cycle sprint workouts 3 days apart. During the workouts, the cyclists did three 20-second “all-out” cycle sprints, resting 2 minutes between each, and while listening to “motivational” music (selected by the scientists), an educational podcast, or nothing.

(The motivational songs were Calvin Harris’ “Let’s Go,” Macklemore’s “Can’t Hold Us,” and Linkin Park’s “Bleed it Out.” Now these artists can say their work has been featured in an academic paper. 😎)

The results showed that listening to music increased people’s heart rate and power output, made them enjoy their workout more, and tended to make them feel better after they’d finished than listening to a podcast or nothing. Interestingly, listening to music didn’t make the workout feel easier.

In other words, although participants worked harder when listening to music, they didn’t feel like they were, and it made training more enjoyable.

These results align with other studies showing listening to muscle improves weightlifting and endurance running performance, especially when you choose music you like.

If you don’t already, listening to your favorite music while training is an effective way to boost your performance in the gym and enjoy your workouts more.

The only time you may want to avoid listening to music is if you’re training for an event that doesn’t allow you to listen to music during the competition.

For example, you aren’t allowed to listen to music during a powerlifting meet, a 5K, or most other races and competitions, so you should do at least some of your workouts without listening to music so you aren’t thrown off come competition day.

(That said, if you are training for a powerlifting meet, some research suggests listening to music during your warm-up and between lifts can boost performance, too.)

TL;DR: Listening to music while exercising boosts your athletic performance and makes working out more enjoyable.

Here’s how female weightlifters can minimize urinary incontinence while training.

Source: “Urinary Incontinence in Competitive Women Weightlifters” published on November 1, 2022 in Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Urinary incontinence (UI) while weightlifting isn’t the sexiest fitness topic.

Nevertheless, it’s an important one.

Involuntarily peeing yourself a little while training is a common problem that occurs in both sexes, especially among women.

Finding ways to deal with it is a high priority among fitness-minded scientists because it’s a barrier that prevents many women from exercising and performing at their best.

To further investigate the link between UI and weightlifting, scientists at Charles Darwin University surveyed 191 competitive female weightlifters aged ~23-to- 48 years old to share their experience of UI.

All of the women had lifted weights for between 2 and 10 years, and ~38% of them had given birth (~76% naturally, ~13% by cesarean, and the remainder had delivered babies naturally and by cesarean).

The survey answers revealed that ~37% of the weightlifters had experienced UI at some point in their lives and ~32% had experienced it during the 3 months before completing the survey.

These numbers are in tune with a previous study showing ~41% of female powerlifters had experienced UI at some point in their lives and ~37% had experienced it while training.

Fifty-seven percent of the women who had experienced UI at some point in their lives had done so during high-rep sets of weightlifting, with most (~68%) saying the problem was worse if the sets were heavy. Half of the women who experienced leakage during high-rep sets said the leakage was more likely to occur at the end of the set.

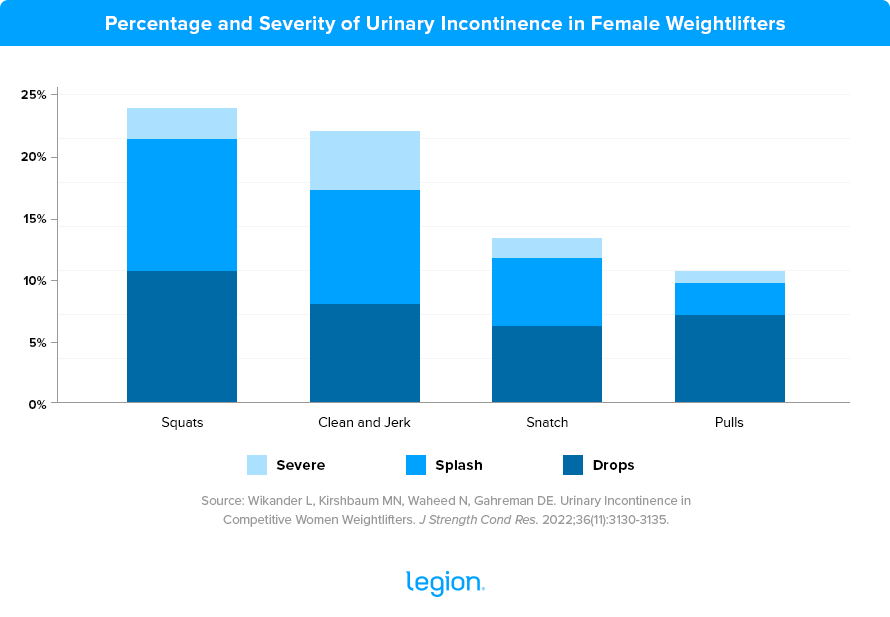

Of all the exercises the weightlifters performed, the most likely to cause leakage was the squat:

(Note: “Pulls” refers to any exercise that involves pulling a weight and could include exercises like the deadlift, rack pull, and power clean.)

It’s not clear why this was, though it might be because the squat involves crouching deeper than the other exercises, thus increasing intra-abdominal pressure (pressure inside your torso) and pressure on your bladder more than lifting a weight from a more upright position.

The researchers also found no connection between how long the women had been training or the amount of weight they could lift with their chances of experiencing UI. This suggests that strength training doesn’t cause UI, but it’s an activity during which UI may manifest.

There are two important takeaways from this study.

The first and most important is that UI is very common among female weightlifters, even those who train and compete regularly. Thus, there’s no reason to feel embarrassed if you experience UI—you’re far from the only one.

Second, the women who participated in this study trained and competed despite their UI. Along the way, they’d learned “tricks” to prevent, minimize, conceal, or contain leakages while weightlifting that might help you do the same.

Here’s what they recommend:

- Take antibiotics to treat urinary tract infections.

- Do yoga or pilates outside of weightlifting.

- Use the bathroom before and frequently during training sessions.

- Engage your pelvic floor muscles before performing an exercise, and do pelvic floor exercises outside of weightlifting.

- Use the Valsalva maneuver, but don’t “over brace.”

- Wear an absorbent pad (or two).

- Stretch your lower back and hips outside of training.

- Emphasize core training.

- Don’t over tighten your weightlifting belt.

- Wear dark clothing to make leaks less visible.

- Don’t drink too much water or coffee before training.

- Stay lean.

- Cross your legs before sneezing.

And if you find that you experience UI while squatting, don’t feel like you have to persist—swap it for the leg press, Bulgarian split squat, or lunge. These exercises are highly effective for training your lower body and don’t require you to lift as much weight or brace as hard, which should make UI less likely.

TL;DR: Urinary incontinence affects many female weightlifters, but you can use a variety of strategies to minimize it.

Late-night eating probably doesn’t increase weight gain.

Source: “Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity” published on October 4, 2022, in Cell Metabolism.

Many people assume that eating late at night automatically causes fat gain.

Although you’ll still hear this idea repeated frequently by celebrities, trainers, and diet gurus, most research shows it’s wrong.

Recently, though, a new study came out that seemed to contradict the majority of research and show that late night eating actually does make you gain fat.

Let’s break it down.

Scientists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital had 16 overweight and obese people follow an “early” and a “late” eating schedule.

On the early schedule, they ate meals at around 8 a.m., 12 p.m., and 4 p.m. On the late schedule, they ate the same meals, only the time of each was shifted forward by around 4 hours. Both schedules lasted 4 days and were eucaloric (the number of calories the participants consumed was equal to their TDEE).

The researchers found that eating later caused a decrease in 24-hour body temperature. This suggests eating later decreases metabolic rate since your body creates heat as it burns energy (calories).

They also calculated the participants’ energy expenditure using indirect calorimetry (a method that involves measuring the gasses a person consumes and produces) and found that eating late decreased waketime energy expenditure by ~5%.

Blood test results showed that eating late altered the ratio of the hormones leptin and ghrelin, too, increasing subjective hunger by ~10%. Furthermore, late eating increased people’s subjective desire to eat and made them crave starchy foods or meat in particular.

Finally, eating late caused subtle shifts in the expression of some genes which are associated with decreased fat burning and increased fat storage.

The obvious conclusion to reach from these results is that eating late at night must cause weight gain. There are two reasons not to assume this is true, though: the researchers didn’t measure weight gain, and the study was very short.

In other words, the findings give us reason to believe that regularly eating late at night could contribute to weight gain over time, but they give us no proof this is actually how things play out.

Fortunately, another study (published on the same day) fills in some of the gaps.

In that study, researchers from the University of Aberdeen had 30 overweight and obese people follow 2 separate weight loss diets for 4 weeks. During one diet, the dieters ate more calories earlier in the day (45% at breakfast, 35% at lunch, and 20% at dinner), and during the other, they ate more calories later in the day (20% at breakfast, 35% at lunch, and 45% at dinner).

The results showed that the dieters burned the same number of calories, had similar metabolic rates, and lost the same amount of weight regardless of when they ate the majority of their calories. The only notable differences between the diets were that eating more later increased the dieters’ hunger, thirst, and desire to eat and made them want to eat larger meals.

There were some differences between these two studies. One studied the effects of shifting your meal schedule. The other kept the same meal schedule but focused the day’s calories toward the beginning or end of the day.

Nevertheless, both results suggest that eating earlier may help reduce hunger.

However, the results from the latter study also suggest that the fluctuations in metabolic rate and energy expenditure seen in the first study may have been overstated and probably won’t significantly affect weight loss over time.

Where does that leave us, then?

Eating earlier, or making your earlier meals larger than your later meals (“breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, dinner like a pauper,” so to speak) may help curb hunger. As such, if you struggle to control your appetite, you may benefit from shifting dinnertime earlier or eating progressively smaller meals as the day wears on.

And what if you don’t struggle to control your hunger? Or you’ve found that eating meals later is more enjoyable?

Then don’t sweat it.

Most studies show that eating later won’t meddle with your metabolism or bias your body to gain fat. In fact, research shows that for some people, skipping breakfast and eating slightly more at lunch and dinner can improve their ability to stick to a diet and thus boost fat loss.

(And if you’d like more specific advice about what diet to follow to reach your fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: Eating earlier or making your earlier meals larger than your later meals may help curb hunger, but this probably isn’t true for everyone and only helps you lose weight if it helps you eat less.

+ Scientific References

- Stork, M. J., Karageorghis, C. I., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2019). Let’s Go: Psychological, psychophysical, and physiological effects of music during sprint interval exercise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, 101547. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHSPORT.2019.101547

- Bartolomei, S., Di Michele, R., & Merni, F. (2015). EFFECTS OF SELF-SELECTED MUSIC ON MAXIMAL BENCH PRESS STRENGTH AND STRENGTH ENDURANCE. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 120(3), 714–721. https://doi.org/10.2466/06.30.PMS.120V19X9

- Bigliassi, M., León-Domínguez, U., Buzzachera, C. F., Barreto-Silva, V., & Altimari, L. R. (2015). How does music aid 5 km of running? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(2), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000627

- Ballmann, C. G., McCullum, M. J., Rogers, R. R., Marshall, M. R., & Williams, T. D. (2021). Effects of Preferred vs. Nonpreferred Music on Resistance Exercise Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(6), 1650–1655. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002981

- Ballmann, C. G., Favre, M. L., Phillips, M. T., Rogers, R. R., Pederson, J. A., & Williams, T. D. (2021). Effect of Pre-Exercise Music on Bench Press Power, Velocity, and Repetition Volume. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 128(3), 1183–1196. https://doi.org/10.1177/00315125211002406

- Wikander, L., Kirshbaum, M. N., Waheed, N., & Gahreman, D. E. (2022). Urinary Incontinence in Competitive Women Weightlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(11), 3130–3135. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004052

- Skaug, K. L., Engh, M. E., Frawley, H., & Bø, K. (2022). Prevalence of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, Bother, and Risk Factors and Knowledge of the Pelvic Floor Muscles in Norwegian Male and Female Powerlifters and Olympic Weightlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(10), 2800–2807. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003919

- Brown, W. J., & Miller, Y. D. (2001). Too wet to exercise? Leaking urine as a barrier to physical activity in women. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 4(4), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1440-2440(01)80046-3

- Gram, M. C. D., & Kari, B. (2020). High level rhythmic gymnasts and urinary incontinence: Prevalence, risk factors, and influence on performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/SMS.13548

- Wikander, L., Kirshbaum, M. N., Waheed, N., & Gahreman, D. E. (2022). Urinary Incontinence in Competitive Women Weightlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(11), 3130–3135. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004052

- Wikander, L., Cross, D., & Gahreman, D. E. (2019). Prevalence of urinary incontinence in women powerlifters: a pilot study. International Urogynecology Journal, 30(12), 2031–2039. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00192-019-03870-8

- Vujović, N., Piron, M. J., Qian, J., Chellappa, S. L., Nedeltcheva, A., Barr, D., Heng, S. W., Kerlin, K., Srivastav, S., Wang, W., Shoji, B., Garaulet, M., Brady, M. J., & Scheer, F. A. J. L. (2022). Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity. Cell Metabolism, 34(10), 1486-1498.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.007

- Ruddick-Collins, L. C., Morgan, P. J., Fyfe, C. L., Filipe, J. A. N., Horgan, G. W., Westerterp, K. R., Johnston, J. D., & Johnstone, A. M. (2022). Timing of daily calorie loading affects appetite and hunger responses without changes in energy metabolism in healthy subjects with obesity. Cell Metabolism, 34(10), 1472-1485.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CMET.2022.08.001

- Moro, T., Tinsley, G., Pacelli, F. Q., Marcolin, G., Bianco, A., & Paoli, A. (2021). Twelve Months of Time-restricted Eating and Resistance Training Improves Inflammatory Markers and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 53(12), 2577–2585. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002738

[ad_2]

Source link