[ad_1]

There are several deadlift variations, but two of the most common are the conventional deadlift and the sumo deadlift.

As such, people often pit them against one other and argue over which is more effective for gaining muscle and strength.

While many fitness gurus have waded in on the sumo deadlift vs. conventional deadlift debate, it’s often hard to tell whose opinions are based on science or personal preference and anatomy.

This article is different.

We’ll look at what science says about the pros and cons of both of these exercises so you can decide which one is right for you.

What Is the Conventional Deadlift?

The conventional deadlift, often referred to simply as “the deadlift,” is a full-body exercise that involves pulling a weight off the floor until you’re standing tall with your arms straight and the bar at hip height, then returning the bar to the floor.

The main muscles worked by the conventional deadlift are the lats, traps, lower back, glutes, calves, and hamstrings, which are collectively known as the “posterior chain,” though it also trains the quads, forearms, core, and shoulders to a lesser degree, too.

How to Conventional Deadlift

- Position your feet so they’re a bit less than shoulder-width apart with your toes pointed slightly out. Move a loaded barbell over your midfoot so it’s about an inch from your shins.

- Move down toward the bar by pushing your hips back and grip the bar just outside your shins.

- Take a deep breath of air into your belly, flatten your back by pushing your hips up slightly, and then drive your body upward and slightly back by pushing through your heels until you’re standing up straight.

- Reverse the movement and return to the starting position.

What Is the Sumo Deadlift?

The sumo deadlift works the same way as the conventional deadlift, except you position your feet about twice as wide. This means your toes point outward more, your hands grip the bar closer together and inside your legs, and your hips are closer to the bar when you begin the pull.

How to Sumo Deadlift

- Position your feet 1.5-to-2 times the width of your shoulders and point your toes slightly outward, then move a loaded barbell over your midfoot so that it’s about an inch from your shins.

- Drop your butt down, letting your knees bend slightly while staying in line with your feet and keeping your back straight. Your shins should be vertical and you should be able to comfortably grip the bar.

- Take a deep breath and stand up while dragging the bar up your shins.

- Reverse the movement to return to the starting position.

Sumo Deadlift vs. Conventional Deadlift: What’s the difference?

When most people talk about the difference between the sumo deadlift and the conventional deadlift, they focus on a few key aspects of each exercise:

- Range of motion

- Muscle activation

- Safety

Let’s look at each.

Range of Motion

When doing the conventional deadlift, you have to lift the bar ~20-to-25% further to reach “lockout” (the point when you’re standing up straight and the rep is complete) than you do when sumo deadlifting.

This has to do with the starting position of your hips, but it’s not worth getting into the nitty-gritty anatomy. The important point is that the conventional deadlift involves a greater range of motion than the sumo deadlift.

Many people believe this makes the sumo deadlift “easier” because lifting a weight through a shorter range of motion generally allows you to lift heavier weights. It’s also why you often hear people say that the sumo deadlift is “cheating.”

It isn’t.

In reality, the conventional deadlift and sumo deadlift are roughly comparable in difficulty. The reason for this is that much of the additional range of motion that you have to move through during the conventional deadlift isn’t all that difficult. Basically, you’re using a greater range of motion, but this extra range of motion isn’t overly taxing.

Whether you pull sumo or conventional, you must complete the hardest part of each rep—the portion between breaking the bar off the floor and lifting it past your mid-shin.

Therefore, it doesn’t matter that the conventional deadlift has a longer range of motion—the extra 20-to-25% is the “easy” part, which shouldn’t have much bearing on whether you complete a rep.

The only time that the sumo deadlift’s shorter range of motion might benefit you is during a high-rep set. That’s because over the course of a multi-rep set, you would have to do less total work than a conventional deadlifter, which should allow you to do more reps with heavier weights before you fatigue.

This “benefit” is a double-edged sword, though.

On the one hand, doing more reps with heavier weights should lead to more muscle and strength gain over time.

On the other hand, training through a shorter range of motion is generally worse for building muscle and getting stronger.

Thus, it’s difficult to know whether sumo’s shorter range of motion is a net positive or negative. If I had to guess, I’d say the reduced range of motion likely negates any benefit of being able to lift a little extra weight, making the gains from sumo and conventional deadlifting more or less equal.

Verdict: Although the conventional deadlift involves a slightly greater range of motion than the sumo deadlift, the differences are too small to matter.

Muscle Activation

Because the sumo and conventional deadlift feel quite different, many people assume they train your muscles differently.

However, research shows that the sumo and conventional deadlift produce about the same total muscle activation, and that both exercises train most of the same muscles to a similar degree.

The one exception is that the sumo deadlift activates your quads slightly more, while the conventional deadlift emphasizes your back muscles.

Even so, the differences in muscle activation are minor (about 10% plus or minus in both cases). What’s more, higher levels of muscle activation don’t necessarily equate to more muscle growth, so it’s difficult to know how much these small variations matter.

Verdict: Both the sumo and conventional deadlift train the same muscles to roughly the same degree, and thus should be about equally effective for gaining muscle and strength.

Safety

Many people fear that deadlifting is bad for your back, but if you’re healthy and use proper form, both conventional and sumo deadlifting is perfectly safe.

In fact, some research suggests that the deadlift is the best exercise you can do to train the paraspinal muscles (the muscles that run down both sides of your spine and play a major role in preventing back injuries). According to at least one study, it may even be effective at treating lower back pain.

That said, some aspects of sumo deadlift form may make it marginally safer for people with a history of lower-back issues.

For instance, you perform the sumo deadlift with a more upright posture and a wider stance than you use for the conventional deadlift. This decreases the shear forces (forces that act on one part of the body in one direction and another in the opposite direction) acting on your lower back, making sumo deadlifting more comfortable for some people.

Your back will experience shear forces no matter how you deadlift, but so long as you use proper form and progress gradually, these forces are well within the limits of what your spine can handle.

Verdict: The sumo deadlift may be more comfortable for people with lower-back pain, but both exercises are safe when performed with proper form.

Sumo or Conventional: How to Choose the Right Deadlift for You

Experience

The sumo deadlift is slightly more technical than the conventional deadlift and requires considerably more flexibility to perform correctly, which is why I don’t recommend beginners start with the sumo deadlift.

A better strategy is to learn how to deadlift conventionally and stick with it for at least your first 6-to-12 months of weightlifting. If you think you’d be better suited to the sumo deadlift after that time, give it a try.

The only exception to this rule is if you try the conventional deadlift and find it too uncomfortable (it causes lower-back or hip pain, for example). In this scenario, feel free to start with sumo—just be prepared for a steeper learning curve.

Hip Structure

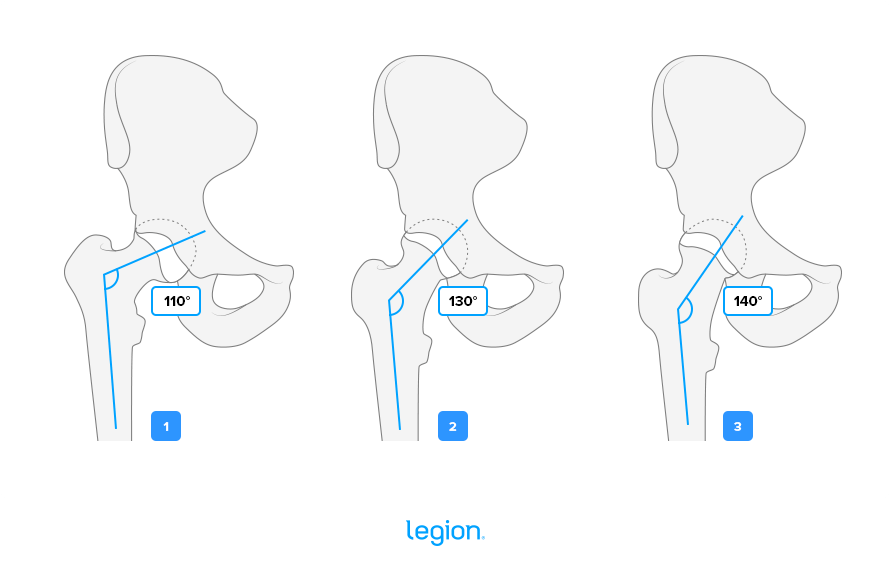

Depending on how your femurs (thigh bones) attach to your hips, you may find one type of deadlift more comfortable than another. Here’s a diagram showing how most people’s femurs attach to their hips:

If your femur attaches at a ~120-degree angle (like picture 2 above), then you may find the sumo and conventional deadlift equally comfortable.

If your femur attaches at a ~110-degree angle (like picture 1), however, then sumo deadlifting might feel very uncomfortable because the top of your femur will run into your hip bone when you try to deadlift with a wide stance.

And if your femur attaches at an extremely obtuse angle of ~140 degrees or more (the third example), then you may prefer the sumo deadlift.

There are convoluted tests you can do to understand which type of hips you have, but this is unnecessary for most people. A more straightforward method is trying both stances and identifying which produces pain, tightness, a pinching sensation, or discomfort. Once you’ve established this, you should have a pretty good idea of which version to do regularly and which to shelve.

Anthropometry

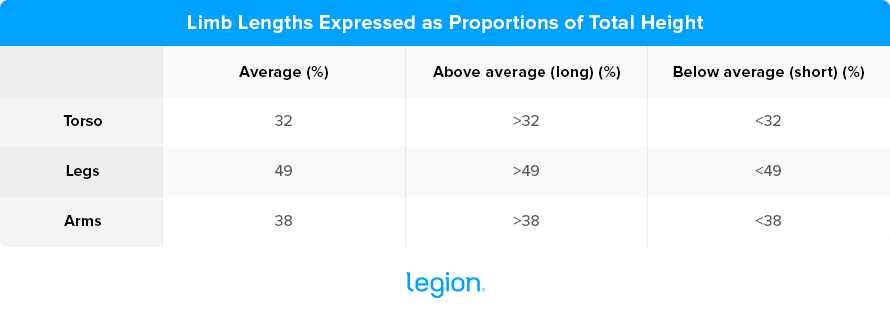

Another factor that can influence whether you’re better suited to sumo or conventional deadlifting is the length of your arms and legs relative to your torso.

To establish whether you have long or short limbs take a measuring tape and record the length of your . . .

- Torso from the widest part of your hip bone to the top of your shoulder joint

- Leg from the widest part of your hip bone to the bottom of your foot

- Arm from your shoulder joint to the tip of your middle finger

- Entire body, from the top of your head to the bottom of your foot

Then use this table to establish whether you have long, short, or average limb lengths:

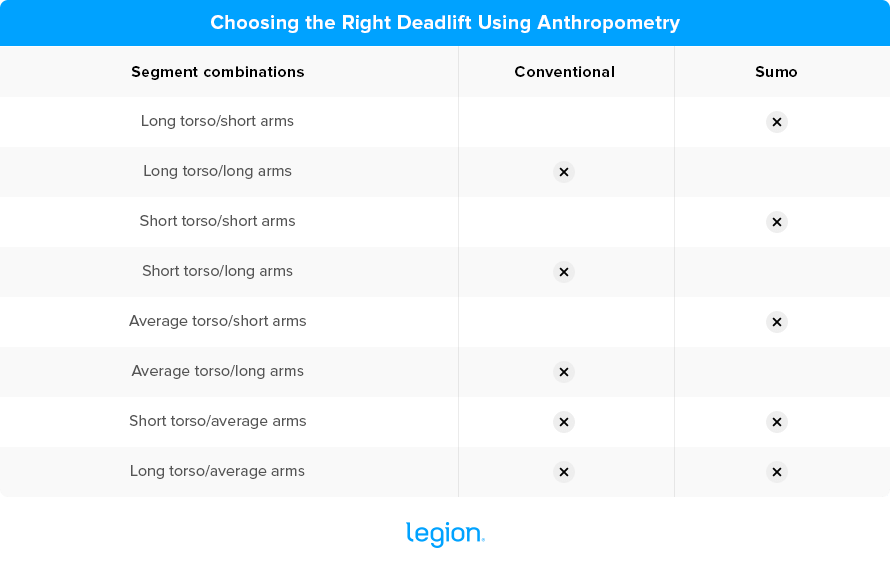

Once you know how you measure up, use this table to establish whether sumo or conventional is best for you:

Preference

Your preference is perhaps the most important factor to consider when deciding which deadlift style to use.

Deadlifting is generally considered the most physically and mentally demanding exercise you can do, which is why choosing the style you enjoy doing makes sense.

Your experience level, hip structure, and bodily proportions will inform your fancy because you’ll probably prefer doing the style that feels most comfortable.

However, for many people, both variations will feel similar. If this is the case for you, the only criteria that you need to satisfy are that you can perform the exercise with proper form and that you enjoy it.

And what if you can perform and enjoy both?

Do both. A good way to do this is to include the conventional deadlift in your program for 8-to-10 weeks of training, take a deload, then replace the conventional deadlift with the sumo deadlift for the following 8-to-10 weeks of training.

Then, you can either continue alternating between the exercises every few months or stick with the one you prefer for an extended period. While there isn’t much evidence to support this particular approach to periodization, there’s a strong theoretical argument that this may reduce your risk of overuse injuries (which are caused by performing the same movements over and over without adequate rest).

This is how I personally like to organize my training, and it’s similar to the method I advocate in my fitness book for intermediate and advanced weightlifters, Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger (the main differences being that you stick with one variation for 16 weeks before switching to something else, and that you also do trap-bar deadlifts).

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about organizing the exercises in your training program to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

Conclusion

Many people paint the sumo and conventional deadlift as wildly different exercises, but research shows they’re far more alike than they are different: they’re equally challenging, train the same muscles to a similar degree, and neither is inherently dangerous, provided you do them with proper form.

Neither is “better” than the other.

That said, there are times when one will be better suited to someone than the other. For example, the conventional deadlift is generally better for new weightlifters because it’s easier to learn. On the other hand, the sumo is often a better option if you have a history of back issues, since it places slightly less strain on your spine.

How your body is put together can make one more comfortable than the other, too. The easiest way to find which fits your body type best is to try both and see which one feels right. In many cases, both will be workable. That’s why the only thing that should influence most people’s decisions is which they like doing more.

+ Scientific References

- Noe, D. A., Mostardi, R. A., Jackson, M. E., Porterfield, J. A., & Askew, M. J. (1992). Myoelectric activity and sequencing of selected trunk muscles during isokinetic lifting. Spine, 17(2), 225–229. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199202000-00018

- Carbe, J., & Lind, A. (2014). A kinematic, kinetic and electromyographic analysis of 1-repetition maximum deadlifts. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/36235

- Camara, K. D., Coburn, J. W., Dunnick, D. D., Brown, L. E., Galpin, A. J., & Costa, P. B. (2016). An examination of muscle activation and power characteristics while performing the deadlift exercise with straight and hexagonal barbells. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(5), 1183–1188. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001352

- Lee, S., Schultz, J., Timgren, J., Staelgraeve, K., Miller, M., & Liu, Y. (2018). An electromyographic and kinetic comparison of conventional and Romanian deadlifts. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness, 16(3), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JESF.2018.08.001

- ESCAMILLA, R. F., FRANCISCO, A. C., KAYES, A. V., SPEER, K. P., & MOORMAN, C. T. (2002). An electromyographic analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34(4), 682–688. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200204000-00019

- Fauth, M. L., Garceau, L. R., Lutsch, B., Gray, A., Szalkowski, C., Wurm, B., & Ebben, W. P. (2010). HAMSTRINGS, QUADRICEPS, AND GLUTEAL MUSCLE ACTIVATION DURING RESISTANCE TRAINING EXERCISES. ISBS – Conference Proceedings Archive. https://ojs.ub.uni-konstanz.de/cpa/article/view/4415

- Camara, K. D., Coburn, J. W., Dunnick, D. D., Brown, L. E., Galpin, A. J., & Costa, P. B. (2016). An Examination of Muscle Activation and Power Characteristics While Performing the Deadlift Exercise With Straight and Hexagonal Barbells. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(5), 1183–1188. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001352

- Krings, B. M., Shepherd, B. D., Swain, J. C., Turner, A. J., Chander, H., Waldman, H. S., McAllister, M. J., Knight, A. C., & Smith, J. E. W. (2021). Impact of Fat Grip Attachments on Muscular Strength and Neuromuscular Activation During Resistance Exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(Suppl 1), S152–S157. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002954

- Hamlyn, N., Behm, D. G., & Young, W. B. (2007). Trunk muscle activation during dynamic weight-training exercises and isometric instability activities. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(4), 1108–1112. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-20366.1

- Escamilla, R. F., Francisco, A. C., Fleisig, G. S., Barrentine, S. W., Welch, C. M., Kayes, A. V., Speer, K. P., & Andrews, J. R. (2000). A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 32(7), 1265–1275. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200007000-00013

- K. Beckham, G., S. Lamont, H., Sato, K., W. Ramsey, M., G., G. H., & H. Stone, M. (2012). Isometric Strength of Powerlifters in Key Positions of the Conventional Deadlift. Journal of Trainology, 1(2), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.17338/TRAINOLOGY.1.2_32

- McMahon, G. E., Morse, C. I., Burden, A., Winwood, K., & Onambélé, G. L. (2014). Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318297143A

- ESCAMILLA, R. F., FRANCISCO, A. C., KAYES, A. V., SPEER, K. P., & MOORMAN, C. T. (2002). An electromyographic analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34(4), 682–688. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200204000-00019

- Escamilla, R. F., Francisco, A. C., Fleisig, G. S., Barrentine, S. W., Welch, C. M., Kayes, A. V., Speer, K. P., & Andrews, J. R. (2000). A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 32(7), 1265–1275. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200007000-00013

- ESCAMILLA, R. F., FRANCISCO, A. C., KAYES, A. V., SPEER, K. P., & MOORMAN, C. T. (2002). An electromyographic analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34(4), 682–688. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200204000-00019

- J Cholewicki, S M McGill, & R W Norman. (n.d.). Lumbar spine loads during the lifting of extremely heavy weights – PubMed. Retrieved September 28, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1758295/

- Vigotsky, A. D., Beardsley, C., Contreras, B., Steele, J., Ogborn, D., & Phillips, S. M. (2017). Greater electromyographic responses do not imply greater motor unit recruitment and “hypertrophic potential” cannot be inferred. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(1), E1–E2. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001249

- Colado, J. C., Pablos, C., Chulvi-Medrano, I., Garcia-Masso, X., Flandez, J., & Behm, D. G. (2011). The progression of paraspinal muscle recruitment intensity in localized and global strength training exercises is not based on instability alone. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(11), 1875–1883. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APMR.2011.05.015

- Holmberg, D., Crantz, H., & Michaelson, P. (2012). Treating persistent low back pain with deadlift training A single subject experimental design with a 15-month follow-up. Advances in Physiotherapy, 14(2), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/14038196.2012.674973

- Gallagher, S., & Marras, W. S. (2012). Tolerance of the lumbar spine to shear: a review and recommended exposure limits. Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol, Avon), 27(10), 973–978. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLINBIOMECH.2012.08.009

- Eltoukhy, M., Travascio, F., Asfour, S., Elmasry, S., Heredia-Vargas, H., & Signorile, J. (2016). Examination of a lumbar spine biomechanical model for assessing axial compression, shear, and bending moment using selected Olympic lifts. Journal of Orthopaedics, 13(3), 210. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOR.2015.04.002

- Hales, M. (2010). Improving the deadlift: Understanding biomechanical constraints and physiological adaptations to resistance exercise. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(4), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0B013E3181E5E300

[ad_2]

Source link