[ad_1]

Maintaining good health is essential for living a long and happy life.

However, assessing your overall health can be challenging. That’s why tracking certain health measures can be helpful.

Rootle around the internet, and you’ll find a litany of health metrics that wellness “gurus” say you should track.

In truth, most of these are unnecessary. You can get a solid picture of your health by monitoring a handful of benchmarks.

In this article, you’ll learn the only health markers you need to track to ensure you’re in good health, why they’re beneficial, and what you need to do to improve them.

What Are Health Metrics?

Health metrics (also referred to as “health markers” or “health measures”) are indicators that reflect the state of your physical, mental, or emotional well-being.

Measures of health can range from objective and quantitative measures, such as blood pressure or body mass index (BMI), to subjective and qualitative measures, such as happiness or life satisfaction, but they’re generally expressed numerically.

Typically, people use health metrics to provide insight into how their body is functioning and help them identify areas that need attention.

The Best Health Metrics to Track

You can find countless ways to track your health if you poke around online, but most are unnecessary.

Here are the only health metrics you need to track.

1. Blood Pressure

Blood pressure measures the force of blood against arterial walls as it circulates through the body.

We measure blood pressure in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and express it as two numbers: Systolic and diastolic. Systolic blood pressure measures the pressure in the arteries when the heart contracts (pumps blood), while diastolic blood pressure measures the pressure when the heart rests between beats.

When we write these numbers, we separate them with a forward slash (/), with the systolic reading to the left and the diastolic reading to the right.

Doctors classify 120/80 mmHg as “normal blood pressure” and 130/80 mmHg or higher as “high blood pressure.”

High blood pressure, or hypertension, is a common health problem (almost half of Americans have hypertension) that can increase your risk of heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and other health complications, which is why monitoring your blood pressure is essential.

The best ways to lower high blood pressure are to exercise regularly (any physical activity is beneficial, though weightlifting and cardio are particularly effective), lose weight, reduce sodium intake, quit smoking, get plenty of sleep, and reduce stress.

2. Body Composition

Body composition refers to the proportion of fat mass (body fat) to fat-free mass (muscle, water, bones, organs, and minerals) in your body.

A healthy body composition is high in fat-free mass (especially muscle mass) and low in body fat. An unhealthy body composition is high in body fat and low in fat-free mass (especially muscle mass).

Tracking your body composition is important because it gives you a better understanding of your general health and fitness than using body weight alone.

For example, if you start exercising and gain 2 pounds of muscle at the same time as losing 2 pounds of fat, your weight will stay the same, but your new and improved body composition will have a positive impact on your health.

Specifically, maintaining a healthy body composition reduces your risk of diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers.

You can measure body composition using various methods, including body composition scales, skinfold thickness measurements, bioelectrical impedance, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

However, these methods are less accurate than many people realize. If you want to learn how to measure body composition accurately, follow the advice in this article:

What Is Body Composition and How Do You Measure It?

You improve your body composition by building muscle and losing body fat (and not muscle).

How much muscle you need to gain and how much fat you need to lose depends on your goals. That said, if you want to optimize your general health, here’s what I recommend:

- Men should look to build 20-to-30 pounds of muscle and maintain a body fat percentage of 8-to-15%.

- Women should aim to build 10-to-15 pounds of muscle and maintain a body fat percentage of 18-to-23%.

And if you want a diet and exercise program to help you reach these targets, check out my fitness books Bigger Leaner Stronger for men and Thinner Leaner Stronger for women.

(If you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger is right for you or if another strength training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, take Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

3. Resting Heart Rate

Resting heart rate is the number of times your heart beats per minute when you’re at rest.

A lower resting heart rate is generally associated with better cardiovascular health, which is why athletes and those who regularly exercise typically have lower resting heart rates than sedentary people.

To measure your resting heart rate, take your pulse for 60 seconds after resting (preferably sitting relatively still) for 10 minutes. A healthy resting heart rate is between 60 and 100 beats per minute.

The best ways to reduce a high resting heart rate are to exercise regularly, drink enough water, and maintain a healthy lifestyle (quit smoking, limit alcohol consumption, and reduce stress, for example).

4. Blood Sugar Levels

Blood sugar levels refer to the concentration of glucose (a type of sugar) in your blood.

Your body creates glucose by breaking down the carbohydrates you eat. When this happens, your pancreas secretes the hormone insulin, which transports glucose into your body’s cells to be used for energy or stored as fat for later use.

In people with prediabetes or diabetes, however, the body can’t produce enough insulin or is unable to use it effectively, resulting in high blood sugar levels.

High blood sugar levels, or hyperglycemia, can cause a range of symptoms, including frequent urination, excessive thirst, itchy skin, and fatigue. If your blood sugar levels remain elevated for an extended period, you also increase your risk of numerous health complications, such as heart disease, stroke, and kidney and nerve damage.

(You may also experience low blood sugar levels, or hypoglycemia. This happens when you haven’t eaten enough food, exercised excessively, or taken too much glucose-lowering medication. While hypoglycemia can be unpleasant and even dangerous, it isn’t as much of a concern for people without diabetes.)

There are two types of blood sugar tests: fasting blood sugar and hemoglobin A1C.

A fasting blood sugar test measures your blood sugar levels after you’ve been in a “fasted state” (when your body is finished processing and absorbing nutrients from the food you’ve eaten and insulin levels drop to a “baseline” level) for at least 8 hours.

A hemoglobin A1C test measures your average blood sugar levels over the past 2-to-3 months.

A healthy fasting blood sugar level is below 99 mg/dL, while a healthy hemoglobin A1C level is below 5.7%.

If you monitor your blood sugar levels and find they’re high, you can lower them by exercising, eating a healthy diet, and maintaining a healthy body composition.

(And if you’d like more specific advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.)

5. Cholesterol and Triglyceride Levels

Cholesterol is a pale, waxy compound that’s chemically similar to fat. It’s present in all cells of the body, and your body uses it to make hormones, vitamin D, and chemicals that help you digest food.

The two main types of cholesterol are low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

LDL cholesterol is often referred to as “bad” cholesterol because it can accumulate in the walls of arteries, forming plaque that narrows the lumen (the hollow passageway through which blood flows), increasing your risk of health complications.

HDL cholesterol, on the other hand, is often referred to as “good” cholesterol because it helps remove LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream and transport it to the liver for processing and removal from the body.

Triglycerides are another lipid (fat or fat-like substance) found in the blood that play a vital role in cardiovascular health.

Triglycerides are made up of three fatty acids (hence “tri”) and one glycerol molecule. They’re stored in fat cells and released into the bloodstream when you require energy. They’re also in many foods, especially those high in saturated and trans fats.

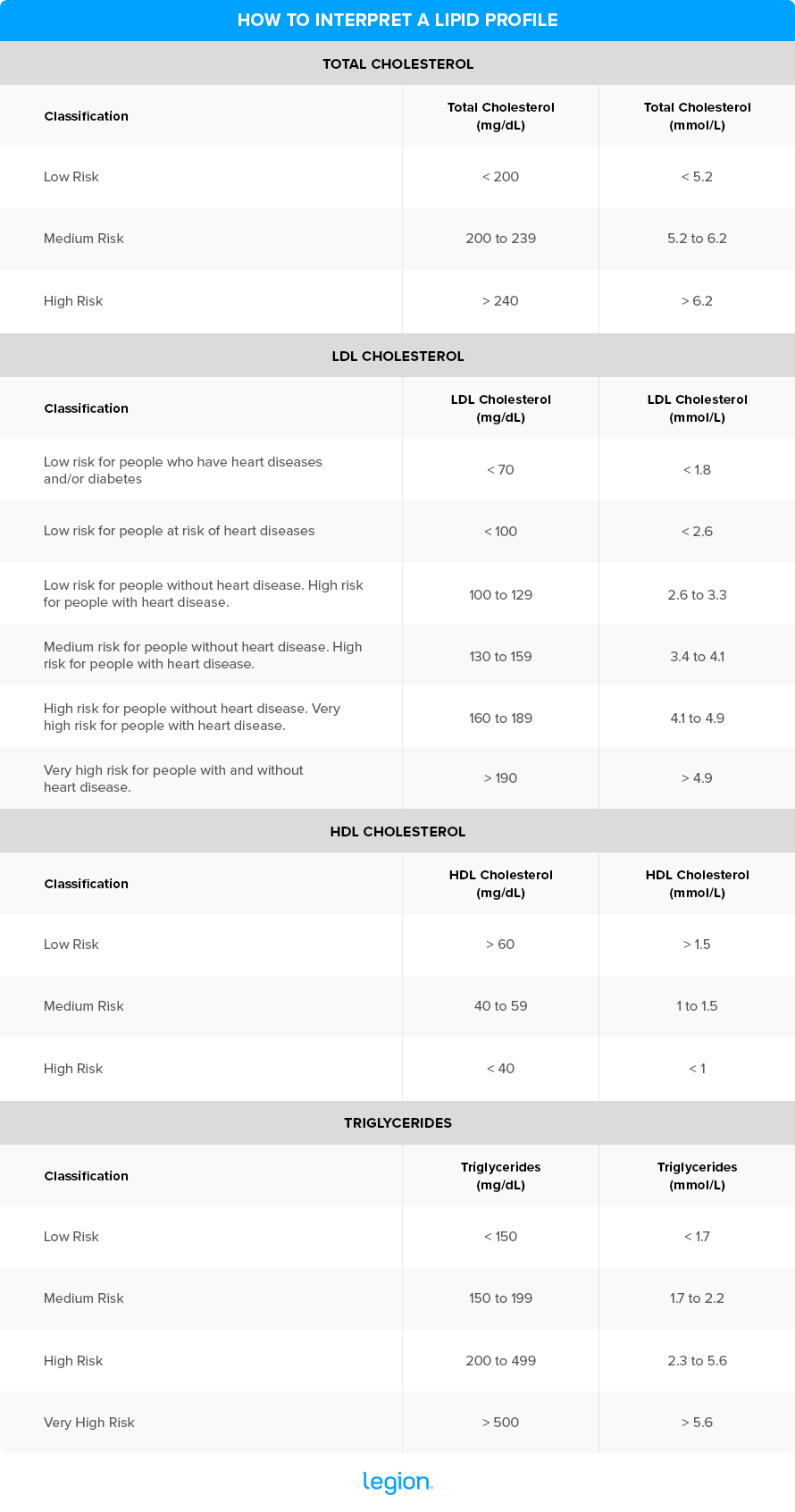

You can monitor your cholesterol and triglycerides with a blood test called a lipid profile, which measures the levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides in your blood.

Making sense of a lipid profile is challenging for most people, though.

That’s because the numbers it gives you are based on massive, complex studies and statistical calculations that can vary based on a long list of factors, including your age, sex, medical history, weight, body composition, lifestyle, medication regimen, and more.

For example, if you’re a young, non-smoking woman with no history of heart disease and a healthy body composition, a “healthy” LDL level for you could be very different than it is for an older, overweight, chain-smoking man.

What’s more, scientists are continually updating these ranges based on the latest evidence.

That said, you can get a general idea of your heart health by looking at the accepted ranges scientists have hashed out over the years.

Here are some good rules of thumb:

Increasing physical activity is the easiest and fastest way to lower your cholesterol, and if you want to see larger drops in LDL cholesterol specifically, focus on high-intensity exercise (like strength training). And while not every overweight or obese person has high LDL or total cholesterol, losing weight generally also helps (and likely raises your HDL cholesterol, too).

+ Scientific References

- Oparil, S., Acelajado, M. C., Bakris, G. L., Berlowitz, D. R., Cífková, R., Dominiczak, A. F., Grassi, G., Jordan, J., Poulter, N. R., Rodgers, A., & Whelton, P. K. (2018). Hypertension. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 4, 18014. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRDP.2018.14

- Carpio-Rivera, E., Moncada-Jiménez, J., Salazar-Rojas, W., & Solera-Herrera, A. (2016). Acute Effects of Exercise on Blood Pressure: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia, 106(5), 422. https://doi.org/10.5935/ABC.20160064

- Arnett, D. K., Blumenthal, R. S., Albert, M. A., Buroker, A. B., Goldberger, Z. D., Hahn, E. J., Himmelfarb, C. D., Khera, A., Lloyd-Jones, D., McEvoy, J. W., Michos, E. D., Miedema, M. D., Muñoz, D., Smith, S. C., Virani, S. S., Williams, K. A., Yeboah, J., & Ziaeian, B. (2019). 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 140(11), e596–e646. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Semlitsch, T., Krenn, C., Jeitler, K., Berghold, A., Horvath, K., & Siebenhofer, A. (2021). Long-term effects of weight-reducing diets in people with hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2021(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008274.PUB4/MEDIA/CDSR/CD008274/IMAGE_N/NCD008274-CMP-001.03.SVG

- Grillo, A., Salvi, L., Coruzzi, P., Salvi, P., & Parati, G. (2019). Sodium Intake and Hypertension. Nutrients, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU11091970

- Andriani, H., Kosasih, R. I., Putri, S., & Kuo, H. W. (2020). Effects of changes in smoking status on blood pressure among adult males and females in Indonesia: a 15-year population-based cohort study. BMJ Open, 10(4), e038021. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2020-038021

- Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. H. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S134864

- Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S., Casey, D. E., Collins, K. J., Himmelfarb, C. D., DePalma, S. M., Gidding, S., Jamerson, K. A., Jones, D. W., MacLaughlin, E. J., Muntner, P., Ovbiagele, B., Smith, S. C., Spencer, C. C., Stafford, R. S., Taler, S. J., Thomas, R. J., Williams, K. A., … Hundley, J. (2021). Estimated Hypertension Prevalence, Treatment, and Control Among U.S. Adults. Hypertension, 71(6), E13–E115. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065

- Spruill, T. M. (2010). Chronic Psychosocial Stress and Hypertension. Current Hypertension Reports, 12(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11906-009-0084-8

- Kuriyan, R. (2018). Body composition techniques. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 148(5), 648. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJMR.IJMR_1777_18

- Avram, R., Tison, G. H., Aschbacher, K., Kuhar, P., Vittinghoff, E., Butzner, M., Runge, R., Wu, N., Pletcher, M. J., Marcus, G. M., & Olgin, J. (2019). Real-world heart rate norms in the Health eHeart study. NPJ Digital Medicine, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41746-019-0134-9

- Reimers, A. K., Knapp, G., & Reimers, C. D. (2018). Effects of Exercise on the Resting Heart Rate: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventional Studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM7120503

- Monnard, C. R., & Grasser, E. K. (2017). Water ingestion decreases cardiac workload time-dependent in healthy adults with no effect of gender. Scientific Reports 2017 7:1, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08446-4

- Ehrenwald, M., Wasserman, A., Shenhar-Tsarfaty, S., Zeltser, D., Friedensohn, L., Shapira, I., Berliner, S., & Rogowski, O. (2019). Exercise capacity and body mass index – Important predictors of change in resting heart rate. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12872-019-01286-2/FIGURES/3

- Orbell, S., Schneider, H., Esbitt, S., Gonzalez, J. S., Gonzalez, J. S., Shreck, E., Batchelder, A., Gidron, Y., Pressman, S. D., Hooker, E. D., Wiebe, D. J., Rinehart, D., Hayman, L. L., Meneghini, L., Kikuchi, H., Kikuchi, H., Desouky, T. F., McAndrew, L. M., Mora, P. A., … Turner, J. R. (2013). Hyperglycemia. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine, 1008–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_1140

- Mouri, Mi., & Badireddy, M. (2022). Hyperglycemia. Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 1314-1315.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-48253-0.00155-0

- Mathew, P., & Thoppil, D. (2022). Hypoglycemia. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534841/

- Kirwan, J. P., Sacks, J., & Nieuwoudt, S. (2017). The essential role of exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 84(7 Suppl 1), S15. https://doi.org/10.3949/CCJM.84.S1.03

- Yau, J. W., Thor, S. M., & Ramadas, A. (2020). Nutritional Strategies in Prediabetes: A Scoping Review of Recent Evidence. Nutrients, 12(10), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU12102990

- Lin, S. F., Fan, Y. C., Chou, C. C., Pan, W. H., & Bai, C. H. (2020). Body composition patterns among normal glycemic, pre-diabetic, diabetic health Chinese adults in community: NAHSIT 2013–2016. PLOS ONE, 15(11), e0241121. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0241121

- Lusis, A. J. (2000). Atherosclerosis. Nature, 407(6801), 233. https://doi.org/10.1038/35025203

- Tada, H., Nohara, A., & Kawashiri, M. A. (2018). Serum Triglycerides and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Insights from Clinical and Genetic Studies. Nutrients 2018, Vol. 10, Page 1789, 10(11), 1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU10111789

- Stone, N. J., Robinson, J. G., Lichtenstein, A. H., Goff, D. C., Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Smith, S. C., Blum, C., Schwartz, J. S., Stone, N. J., Robinson, J. G., Lichtenstein, A. H., Eckel, R. H., Merz, C. N., Bloom, C. B., Goldberg, A. C., Gordon, D., Levy, D., McBride, P., Schwartz, J. S., … Wilson, P. W. (2014). Treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: Synopsis of the 2013 American college of cardiology/American heart association cholesterol guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(5), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0126/SUPPL_FILE/AIME201403040-00009_SUPPLEMENT1.PDF

- Piepoli, M. F., Hoes, A. W., Agewall, S., Albus, C., Brotons, C., Catapano, A. L., Cooney, M. T., Corrà, U., Cosyns, B., Deaton, C., Graham, I., Hall, M. S., Hobbs, F. D. R., Løchen, M. L., Löllgen, H., Marques-Vidal, P., Perk, J., Prescott, E., Redon, J., … Gale, C. (2016). 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). European Heart Journal, 37(29), 2315–2381. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHW106

- Vallejo-Vaz, A. J., Robertson, M., Catapano, A. L., Watts, G. F., Kastelein, J. J., Packard, C. J., Ford, I., & Ray, K. K. (2017). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease among men with primary elevations of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of 190 mg/dL or above: Analyses from the WOSCOPS (West of Scotland coronary prevention study) 5-year randomized trial and 20-year observational follow-up. Circulation, 136(20), 1878–1891. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027966/-/DC1

- Ballantyne, C. M., Birtcher, K. K., Daly, D. D., Depalma, S. M., Minissian, M. B., Orringer, C. E., Smith, S. C., Everett, B. M., Hernandez, A., Hucker, W., Jneid, H., Kumbhani, D. J., Marine, J. E., Morris, P. B., Piana, R., Watson, K. E., & Wiggins, B. S. (2017). 2017 Focused Update of the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Non-Statin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 70(14), 1785–1822. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2017.07.745

- Lavie, C. J., Arena, R., Swift, D. L., Johannsen, N. M., Sui, X., Lee, D. C., Earnest, C. P., Church, T. S., O’Keefe, J. H., Milani, R. V., & Blair, S. N. (2015). Exercise and the cardiovascular system: clinical science and cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation Research, 117(2), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305205

- Mann, S., Beedie, C., & Jimenez, A. (2014). Differential Effects of Aerobic Exercise, Resistance Training and Combined Exercise Modalities on Cholesterol and the Lipid Profile: Review, Synthesis and Recommendations. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44(2), 211. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-013-0110-5

- Shamai, L., Lurix, E., Shen, M., Novaro, G. M., Szomstein, S., Rosenthal, R., Hernandez, A. V., & Asher, C. R. (2011). Association of body mass index and lipid profiles: evaluation of a broad spectrum of body mass index patients including the morbidly obese. Obesity Surgery, 21(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11695-010-0170-7

- Kaur, J. (2014). A Comprehensive Review on Metabolic Syndrome. Cardiology Research and Practice, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/943162

- Dansinger, M. L., Gleason, J. A., Griffith, J. L., Selker, H. P., & Schaefer, E. J. (2005). Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA, 293(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.293.1.43

- Williams, P. T., Stefanick, M. L., Vranizan, K. M., & Wood, P. D. (1994). The Effects of Weight Loss by Exercise or by Dieting on Plasma High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) Levels in Men With Low, Intermediate, and Normal-to-High HDL at Baseline. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 43(7), 917. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(94)90277-1

- Castelli, W. P., Anderson, K., Wilson, P. W. F., & Levy, D. (1992). Lipids and risk of coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Annals of Epidemiology, 2(1–2), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/1047-2797(92)90033-M

[ad_2]

Source link