[ad_1]

It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn how long to rest between sets, how to use diet to prevent overtraining, and how drinking alcohol impacts recovery.

Resting longer between sets boosts muscle and strength gain.

Source: “Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men” published in July 2016 in Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Gym lore states that you should rest 3-to-5 minutes between sets if you want to get stronger, and 1-to-2 minutes between sets if you want to gain muscle.

At first blush, this makes sense. Strength training programs are about lifting as much weight as possible. By resting longer between sets, you can add more weight and get stronger faster.

Bodybuilding programs, on the other hand, are generally geared toward doing as many sets and reps as possible in the time you have available. By resting less, you can cram more sets and reps into your workouts and, theoretically, build more muscle.

Some people also claim that shorter rest periods directly stimulate muscle growth.

Is any of this true, though?

That’s what a team of scientists from CUNY Lehman College wanted to find out in this study.

The researchers separated twenty-three 18-to-35-year-old male college students into 2 groups:

- A group that rested one minute between sets.

- A group that rested three minutes between sets.

The researchers divided the weightlifters into these groups based on their squat one-rep max to ensure that both groups were similarly strong.

Both groups followed the same 3-day workout routine for 8 weeks, which involved doing 3 sets of the bench and overhead press, squat, leg press, leg extension, lat pulldown, and cable row, all in the 8-to-12 rep range.

The researchers asked the participants to maintain their normal eating habits and refrain from taking any workout supplements besides a post-workout whey protein shake on their training days.

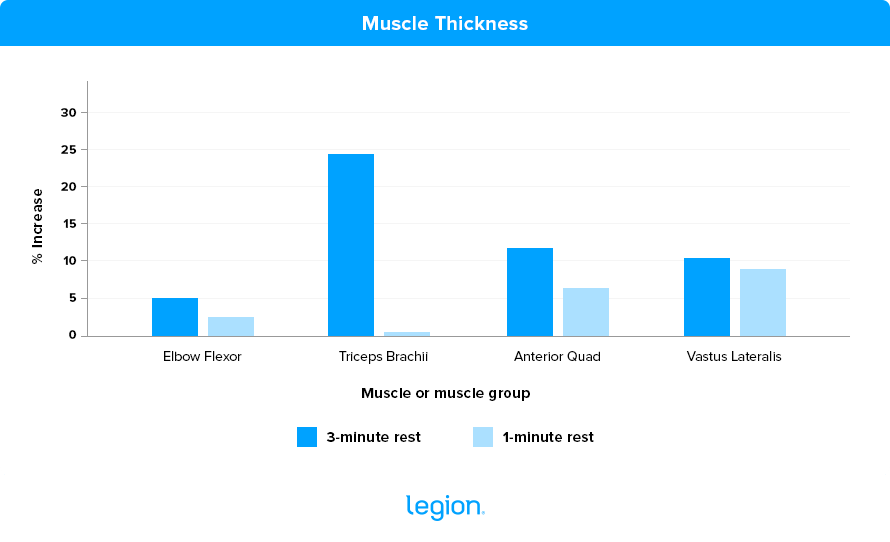

The results showed that while both groups made progress, the group that rested 3 minutes built significantly more muscle than the group that rested 1 minute. Here’s how the results looked:

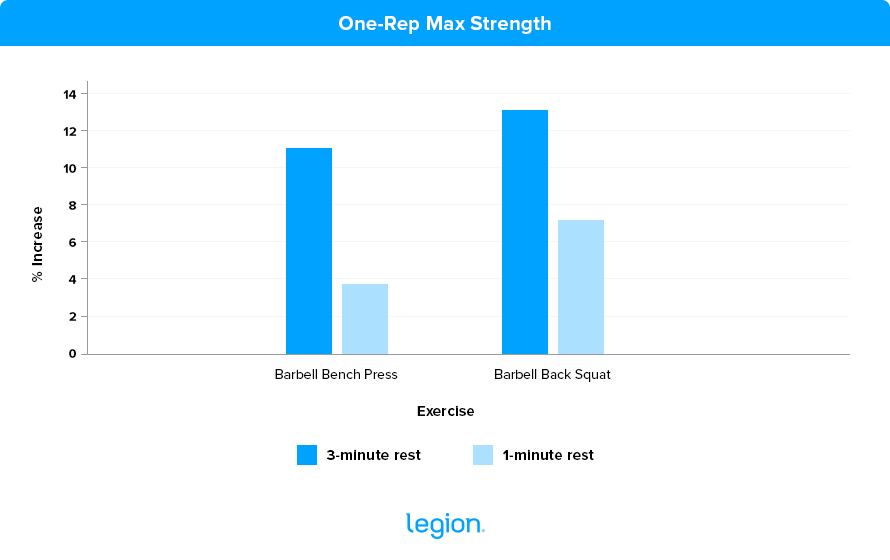

The 3-minute rest group fared even better when looking at strength gain:

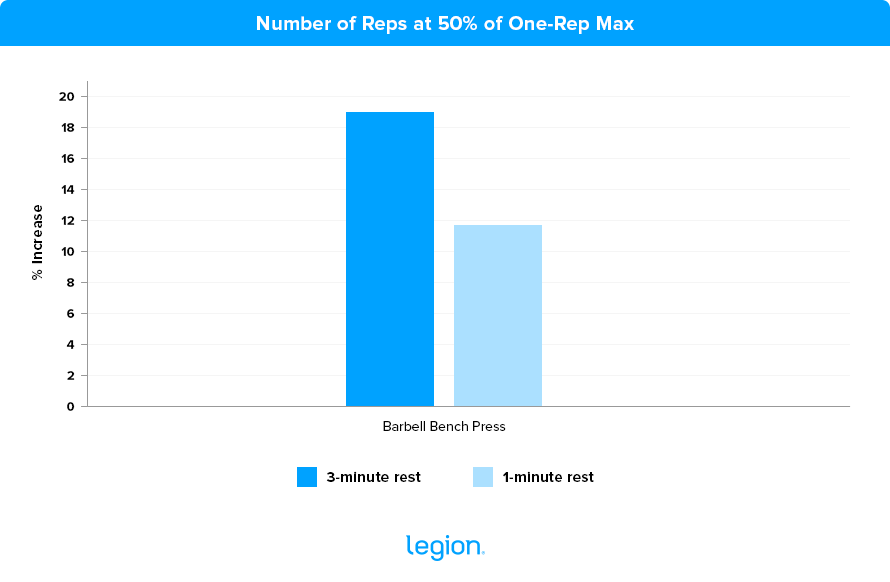

The 3-minute rest group also improved the number of reps they could bench press with 50% of their one-rep max significantly more than the 1-minute rest group:

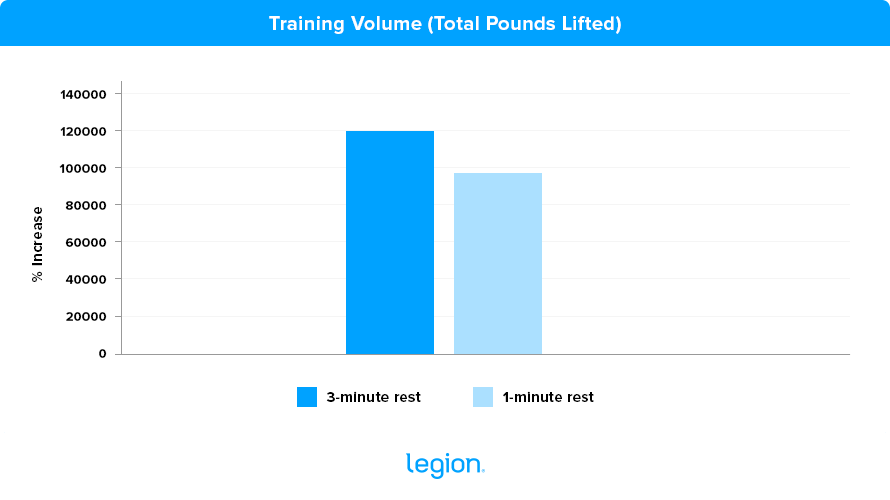

Finally, the 3-minute group did about 20% more total volume load (weight x sets x reps) than the 1-minute group, which is generally correlated with greater muscle gain over time. Here’s what the results looked like:

This meant the 3-minute group did about 20% more training volume than the 1-minute group. This wasn’t enough to reach statistical significance in this study, but it probably would have if the study had used more subjects or lasted longer.

All in all, the group that rested 3 minutes clobbered the group that rested 1 minute on every level.

And this jives with the findings of several studies, which have all concluded that if you want to get big and strong as fast as possible, rest more between sets, not less.

At this point, you may be thinking, “I barely have time to work out as it is, how am I supposed to make more time to rest between sets?”

Here’s the solution:

Do fewer sets and exercises, use heavier weights, and use the extra time to rest longer between sets.

You don’t necessarily have to rest exactly 3 minutes between every set to get bigger and stronger, but you should generally rest as long as you need to give your best effort on every set.

This may sound counterintuitive, but this “quality over quantity” approach is not only well-supported scientifically, it’s also helped thousands of people gain strength and muscle as fast as possible on my fitness programs for men and women: Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about how to structure your workouts to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: Resting 3 minutes between sets helps you gain more muscle, strength, and endurance than resting 1 minute between sets.

Feeling overtrained? You probably need to eat more.

Source: “Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities” published on June 28, 2021 in Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.).

“There’s no such thing as overtraining—just undereating.”

You’ll sometimes hear this bromide bandied about by fitness influencers, and while it’s factually incorrect, it contains a kernel of truth.

While true overtraining is very rare (especially among weightlifters), overreaching is fairly common.

Overreaching is basically a foretaste of overtraining: it also involves fatigue, irritability, insomnia, and a marked decrease in performance, and it’s also typically caused by training too hard for too long without sufficient rest.

Given that calorie intake plays a significant role in your ability to recover from workouts, scientists at the Pacific Institute for Sport Excellence wanted to test if overreaching could be partially or completely ameliorated by simply eating more food. Or, put differently, is overreaching made worse or sometimes entirely caused by undereating?

In this scientific review, researchers analyzed 21 studies that had endurance athletes (cyclists, middle- or long-distance runners, triathletes, rowers, and swimmers) follow training programs intended to cause overtraining or overreaching while also giving details about their diets and body composition.

Firstly, they found that it was remarkably difficult to cause overreaching or overtraining, which is in line with previous studies on this topic.

Among people who did begin to feel frazzled, the scientists found that the symptoms associated with overtraining and overreaching closely mimicked those of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), a condition that occurs when you provide your body with too few calories to maintain optimal health once you account for the energy burned through training.

In other words, they found that it’s possible to have all the signs of overtraining or overreaching, but not actually have either, and instead have a condition caused by eating too few calories.

Further analysis showed that in 14 of the studies, the athletes who showed signs of overtraining consumed a meager amount of calories compared to those who stayed symptom-free. In another 4 studies, the overtrained folks were limiting their carb intake more than the athletes who didn’t experience any ill effects.

The primary takeaways from this study are:

- It’s much harder to “overtrain” or “overreach” than most weightlifters realize.

- Most cases of “overreaching” are almost certainly exacerbated or driven by undereating.

If you’re currently lean bulking, then the solution is simple: eat more.

But what if you’re trying to maintain or even lose body fat, and you need to keep your calorie intake relatively low?

In this case, you may still want to eat a bit more than you are now (while staying in a calorie deficit), but more importantly, reduce your training volume by about 10-to-30%, depending on how ragged you’re feeling.

For example, if you’re currently doing 16 sets per workout, which is what you’d do on my Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger program, you’d cut this back to ~12-to-14 sets.

If you’d like even more specific advice about how many sets you should do each week, how often you should train, and what exercises you should do to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: If you think you’re “overtrained,” you probably just need to eat more or, if that’s not a viable option, reduce your weekly training volume by ~10-to-30%.

Drinking alcohol post-workout doesn’t hurt your recovery (but it’s still not a great idea).

Source: “The Effects of Alcohol Consumption on Recovery Following Resistance Exercise: A Systematic Review” published on June 26, 2019 in Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology.

While everyone knows drinking large amounts of alcohol is unhealthy, some folks say that having just a single drink after you work out can undermine your recovery.

A new meta-analysis from scientists at the University of Palermo suggests that a little tipple after training isn’t so bad after all.

The authors found 12 studies that investigated how alcohol affects recovery by looking at a variety of factors, such as hormone levels, heart rate, muscle protein synthesis rate, strength, soreness, rating of perceived exertion, and cognition.

In the main, drinking alcohol after working out had a negligible impact on most variables:

- Drinking didn’t seem to impact how quickly muscles repaired themselves after training (as measured by creatine kinase levels).

- Light-to-moderate drinking (less than ~0.23 grams of alcohol per pound of body weight, or about ~3 servings for a 180-lb. man) had little impact on how quickly men regained strength and power after a workout.

- Strangely, being drunk didn’t appear to make people weaker. That said, most of the exercises used in these studies required very little skill, and the weightlifters probably would have performed worse if they’d been doing the squat, deadlift, or bench press.

That said, drinking after training did earn a few demerits:

- Drinking alcohol after a particularly intense workout might adversely affect recovery more than drinking after a typical workout. (Slamming beers after setting a new one-rep max probably isn’t wise).

- Heavy drinking (≥0.45 grams of alcohol per pound of body weight, or about 6 drinks for a 180-lb. man) slowed the rate at which men recovered their strength after training. The same was not true for women, who seemed to regain their strength after training regardless of how much they drank (which may be due to their higher estrogen levels, ability to process alcohol faster than men, or because they drank less alcohol in absolute terms).

- Drinking after training may undermine muscle growth by increasing blood levels of cortisol and reducing amino acids, testosterone, and muscle protein synthesis rates. While most research shows that light-to-moderate drinking doesn’t interfere with hypertrophy, it may be best to avoid drinking immediately after your workouts if your main goal is to build muscle.

On the whole, this study validates common sense: Occasional, moderate drinking—even right after training—won’t significantly interfere with your health and fitness goals. What’s more, most studies define “moderate” drinking as up to ~3 drinks per day, which is far more than most health conscious people consume.

Thus, a single beer, glass of wine, or cocktail isn’t worth worrying about.

That said, it goes without saying that if you regularly get trolleyed after training, your workouts (and life) will suffer.

TL;DR: Occasionally having a drink or two of alcohol after training is unlikely to interfere with your recovery, performance, or ability to gain muscle and strength.

+ Scientific References

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Pope, Z. K., Benik, F. M., Hester, G. M., Sellers, J., Nooner, J. L., Schnaiter, J. A., Bond-Williams, K. E., Carter, A. S., Ross, C. L., Just, B. L., Henselmans, M., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(7), 1805–1812. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272

- Senna, G. W., Figueiredo, T., Scudese, E., & Baffi, M. (n.d.). (PDF) Influence of Different Rest Interval Length in Multi-Joint and Single-Joint Exercises on Repetition Performance, Perceived Exertion, and Blood Lactate. Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273726294_Influence_of_Different_Rest_Interval_Length_in_Multi-Joint_and_Single-Joint_Exercises_on_Repetition_Performance_Perceived_Exertion_and_Blood_Lactate

- Willardson, J. M., & Burkett, L. N. (2005). A comparison of 3 different rest intervals on the exercise volume completed during a workout. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(1), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-13853.1

- Tibana, R. A., Vieira, D. C. L., Tajra, V., Bottaro, M., De Salles, B. F., Willardson, J. M., & Prestes, J. (2013). Effects of rest interval length on Smith machine bench press performance and perceived exertion in trained men. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 117(3), 682–695. https://doi.org/10.2466/06.30.PMS.117X27Z2

- Willardson, J. M., & Burkett, L. N. (2006). The effect of rest interval length on the sustainability of squat and bench press repetitions. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(2), 400–403. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-16314.1

- Scudese, E., Willardson, J. M., Simão, R., Senna, G., De Salles, B. F., & Miranda, H. (2015). The Effect of Rest Interval Length on Repetition Consistency and Perceived Exertion During Near Maximal Loaded Bench Press Sets. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(11), 3079–3083. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSC.0000000000000214

- Ratamess, N. A., Faigenbaum, A. D., Chiarello, C. M., Ross, R. E., Kang, J., Sacco, A. J., & Hoffman, J. R. (2012). The effects of rest interval length on acute bench press performance: the influence of gender and muscle strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(7), 1817–1826. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E31825BB492

- Henselmans, M., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2014). The effect of inter-set rest intervals on resistance exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44(12), 1635–1643. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-014-0228-0

- Buresh, R., Berg, K., & French, J. (2009). The effect of resistive exercise rest interval on hormonal response, strength, and hypertrophy with training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318185F14A

- Hernandez, D. J., Healy, S., Giacomini, M. L., & Kwon, Y. S. (2021). Effect of Rest Interval Duration on the Volume Completed During a High-Intensity Bench Press Exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(11), 2981–2987. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003477

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181E840F3

- Stellingwerff, T., Heikura, I. A., Meeusen, R., Bermon, S., Seiler, S., Mountjoy, M. L., & Burke, L. M. (2021). Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 51(11), 2251–2280. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-021-01491-0

- Grandou, C., Wallace, L., Impellizzeri, F. M., Allen, N. G., & Coutts, A. J. (2020). Overtraining in Resistance Exercise: An Exploratory Systematic Review and Methodological Appraisal of the Literature. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 50(4), 815–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-019-01242-2

- Lakićević, N. (2019). The Effects of Alcohol Consumption on Recovery Following Resistance Exercise: A Systematic Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/JFMK4030041

- Levitt, D. E., Luk, H. Y., Duplanty, A. A., McFarlin, B. K., Hill, D. W., & Vingren, J. L. (2017). Effect of alcohol after muscle-damaging resistance exercise on muscular performance recovery and inflammatory capacity in women. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(6), 1195–1206. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-017-3606-0

- Mishra, L., Sharma, S., Potter, J. J., & Mezey, E. (1989). More rapid elimination of alcohol in women as compared to their male siblings. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 13(6), 752–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1530-0277.1989.TB00415.X

[ad_2]

Source link