The Meadows row is an upper-body pulling exercise involving a barbell and a landmine attachment.

It’s a mainstay of many strength training programs because it helps you to train your entire back without putting much stress on your spine.

It also allows you to train your back unilaterally, which means it’s useful for evening out any size and strength imbalances you might have.

In this article, you’ll learn what the Meadows row is, why it’s beneficial, how to use proper Meadows row form, the best Meadows row alternatives, and more.

What Is the Meadows Row?

The Meadows row is a back exercise performed in a staggered stance using a barbell and a landmine attachment.

It was invented by former bodybuilder, trainer, and online fitness personality John “Mountain Dog” Meadows (hence the name).

Meadows Row: Benefits

1. It trains your entire back.

Exercises that train several muscle groups simultaneously are called compound exercises. They’re useful because they allow you to lift more weight safely, which is generally better for muscle and strength gain.

They’re also more time-efficient because you don’t have to do several exercises to train each muscle group separately.

And if you want a program that contains all the best compound exercises for training your entire body, check out my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger is right for you or if another strength training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, take Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

2. It’s ideal for people with lower-back problems

Unlike many other compound back exercises, such as the barbell row and deadlift, the Meadows row exercise allows you to brace your torso against your leg, which means it lightens the load on your spine (when performed correctly).

This makes it ideal for people trying to train around a back injury.

3. It trains your back unilaterally.

The Meadows row is a unilateral exercise, which means it allows you to train one side of your body at a time.

This is beneficial because unilateral exercises . . .

- May enable you to lift more total weight than you can with some bilateral exercises (exercises that train both sides of the body at the same time), which may help you gain more muscle over time

- Help you develop a greater mind-muscle connection with your lats, traps, and rhomboids because you only need to focus on one side of your body at a time

- Help you correct muscle imbalances, because both sides of your body are forced to lift the same amount of weight (one side can’t “take over” from the other)

- May improve several aspects of your athletic performance more than bilateral exercises

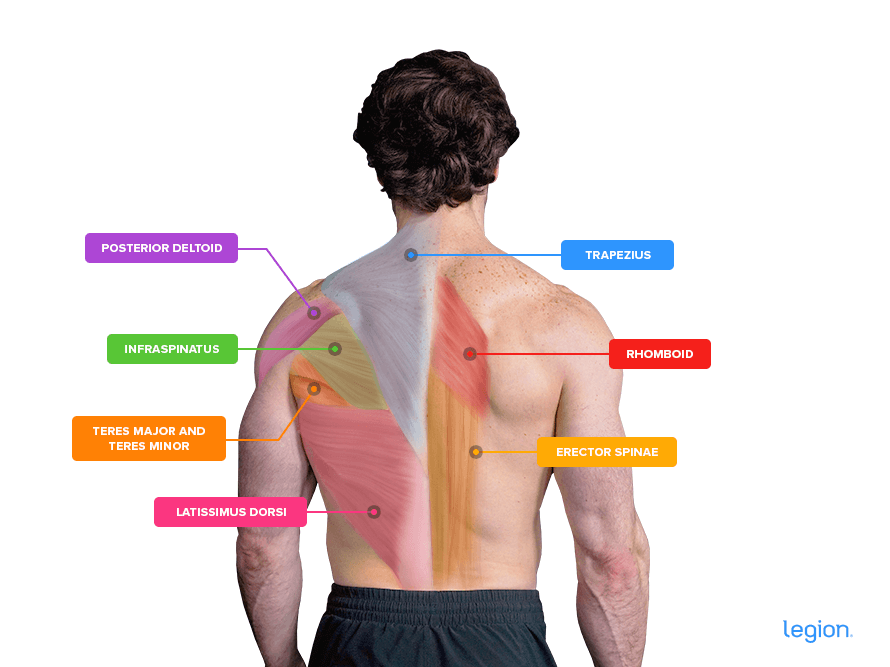

Meadows Row: Muscles Worked

The Meadows row trains all of your back muscles, including the . . .

- Latissimus dorsi

- Trapezius

- Rhomboids

- Teres major and minor

- Infraspinatus

- Posterior deltoid

It also works the erector spinae, forearms and biceps to a lesser extent, too.

Here’s how the main back muscles worked by the Meadows row look on your body:

Meadows Row: Form

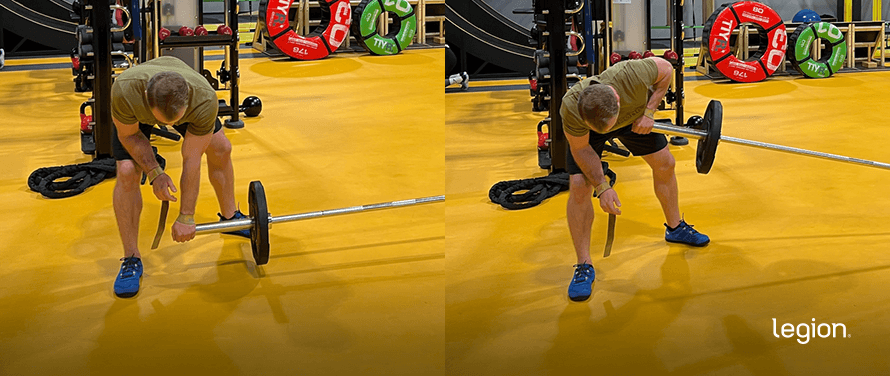

The best way to learn how to perform the Meadows row is to break it into three parts: set up, row, and extend.

1. Set Up

Wedge one end of a barbell into the corner of the room or insert it into a landmine attachment and load the other end with weight.

Position your right foot perpendicular to the barbell and around 6-to-8 inches from the weighted end. Place your left foot 6-to-8 inches behind the weight plates (staggered stance), with your toes facing whatever direction is most comfortable.

Bend both knees, bend over at the waist so your back is almost parallel with the floor, and place your right forearm on your right thigh.

While keeping your back flat, grab the end of the barbell with your left hand. If you’re using lifting straps, wrap the strap around the barbell.

2. Row

Keeping your back flat, pull the barbell until your left hand touches your torso and your elbows are about 8-to-10 inches from your left side.

(Tip: A helpful cue is to imagine touching the ceiling with your elbow.)

3. Extend

Once your hand touches your torso, reverse the movement and return to the starting position. This is a mirror image of what you did during the row.

Don’t let the weight yank your arm back to the starting position or try to extend your arm slowly. The entire “extension” should be controlled but only take about a second.

When you’ve completed the desired number of reps, switch sides and repeat the process with your right arm.

Here’s how it should look when you put it all together:

The Best Meadows Row Alternatives

1. One-Arm Dumbbell Row

The downside, however, is you can only progress up to the heaviest dumbbells available in your gym (usually around 100 pounds), whereas with the Meadows row you can continue to add weight for far longer.

This is significant because lifting heavier weights over time is the best way to maximize the muscle-building effects of weightlifting.

2. Seated Cable Row

3. Barbell Row

Because you use a bit of leg drive to get the bar moving, you can generally lift more weight with the barbell row than you can with other back exercises. This is one of the reasons research shows that the barbell row is highly effective for training your entire back.

+ Scientific References

- Ronai, P. (2019). Do It Right: The Seated Cable Row Exercise. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal, 23(4), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1249/FIT.0000000000000492

- Graham, J. F. B. C. D. (n.d.). Dumbbell One-Arm Row : Strength & Conditioning Journal. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Citation/2001/04000/Dumbbell_One_Arm_Row.14.aspx

- Jakobi, J. M., & Chilibeck, P. D. (2001). Bilateral and unilateral contractions: possible differences in maximal voluntary force. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology = Revue Canadienne de Physiologie Appliquee, 26(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1139/H01-002

- Janzen, C. L., Chilibeck, P. D., & Davison, K. S. (2006). The effect of unilateral and bilateral strength training on the bilateral deficit and lean tissue mass in post-menopausal women. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2006 97:3, 97(3), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-006-0165-1

- Liao, K. F., Nassis, G. P., Bishop, C., Yang, W., Bian, C., & Li, Y. M. (2021). Effects of unilateral vs. bilateral resistance training interventions on measures of strength, jump, linear and change of direction speed: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biology of Sport, 39(3), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.5114/BIOLSPORT.2022.107024

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181E840F3

- Fenwick, C. M. J., Brown, S. H. M., & Mcgill, S. M. (2009). Comparison of different rowing exercises: trunk muscle activation and lumbar spine motion, load, and stiffness. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(2), 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181942019

- Ronai, P. (2017). The Barbell Row Exercise. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal, 21(2), 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1249/FIT.0000000000000278