[ad_1]

It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn what to do if you feel like you aren’t getting fitter despite training properly, the healthiest way to bulk, and whether fish oil boosts post-workout recovery.

Here’s what to do if you aren’t getting fitter (despite training properly).

Source: “Individual differences in the responses to endurance and resistance training” published on December 21, 2005 in European Journal of Applied Physiology.

“No matter what I do, I just can’t seem to get any fitter.”

This is the conclusion many people reach after their first few months of training when the rapid progress they initially experienced stagnates, and further gains seem impossible to come by.

Is it really the case that exercise only benefits some people for a short while (during their “newbie gains” phase), after which they stop getting noticeably fitter? Or is it simply that they haven’t found a form of exercise that works for them long term?

This is what scientists at Merikoski Rehabilitation and Research Centre wanted to understand when they split 73 men and women into a cardio group and a weightlifting group.

For 2 weeks, the cardio group did endurance training, and the weightlifting group did strength training 5 days per week.

After 2 weeks, everyone stopped exercising (or returned to their old exercise habits) for 2 months, then came back to the lab to undergo the same process. The only difference was that this time, those who did endurance training lifted weights and vice versa.

The results showed that after the first 2 weeks, some people in each group responded well to training (measured using VO2 max, which is an indicator of endurance that can increase due to cardio or weightlifting), others responded a little, and still others saw no gains.

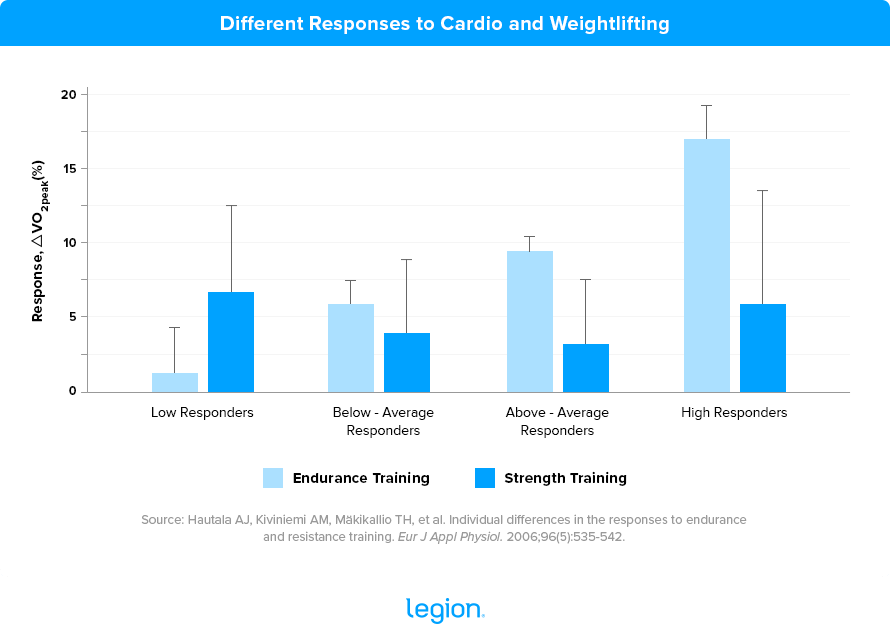

When the groups switched programs, the researchers found that the people who got the smallest gains from cardio got the biggest gains from weightlifting and vice versa. Thus, these supposed “non-responders” responded quite well to exercise when it was tailored to their unique physiology. Here’s a graph to illustrate:

The most important nugget to take away from this study (and others like it) is that it’s improbable that exercise will just “stop working” for you, though you may need to periodically alter your training to make progress.

For example, if you begin your training career doing high-rep weightlifting and find your progress stalls within the first few months, you should probably try a program that has you lifting heavier weights, such as Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

And if that doesn’t work for you, you could try your hand at bodybuilding, powerlifting, powerbuilding, strongman, Olympic weightlifting, CrossFit, circuit training, or something else.

And if you’d like help choosing the best strength training program for your circumstances and goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.

TL;DR: The same workout program might not work equally well for everyone, but everyone can benefit from some kind of exercise—you just have to find the right type for you.

The healthiest way to bulk? Eat plenty of protein.

Source: “Protein Overfeeding is Associated with Improved Lipid and Anthropometric Profile thus Lower Malondialdehyde Levels in Resistance-Trained Athletes” published in January 2017 in International Journal of Sports Science.

Most fitness buffs enjoy bulking.

What’s not to like about eating satisfyingly large meals, having sky-high energy levels, and building muscle?

Bulking is still just a form of controlled overeating, though, and some worry that this can lead to negative health consequences related to gaining body fat. For example, research shows that during a bulk, your body fat percentage and blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels rise, which can increase oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and insulin resistance.

Fortunately, researchers at the Federal University of Ceará may have uncovered a way to keep you in tip-top health, even while “gaining,” “massing,” or whatever other term you want to use for “bulking.”

They took 19 bodybuilders who were bulking (eating ~23 calories per pound of body weight per day—which is a lot) and split them into a standard bulking group and a high-protein bulking group based on how much protein they ate each day.

The bodybuilders in the standard bulking group were eating ~0.7 grams of protein per pound of body weight. In contrast, the bodybuilders in the high-protein bulking group were eating ~1.4 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day. The bodybuilders in each group were also eating similar amounts of fat and fiber, though those in the standard bulking group were eating more carbs and cholesterol.

The researchers then ran a barrage of blood tests and found that the bodybuilders in the high-protein bulking group had better cholesterol levels, less body fat (particularly around the waist), and less oxidative stress and better health overall as a result.

On the face of it, this looks like yet another homerun for high-protein dieting—the more protein you eat while bulking, the less fat you gain, and the healthier you’ll be, right?

The truth isn’t quite this crystalline.

The main fly in the ointment here is that the researchers didn’t control the bodybuilders’ diets during the study, which opens up the possibility that some other variable was responsible for the superior results in the high-protein group.

For instance, it’s possible that the group eating twice as much protein—which is very satiating—also felt more full and ate less. In essence, eating more protein helped keep them from overeating, which is one of the main reasons people gain fat and undermine their health when bulking.

By my lights, this is the most likely explanation, but it’s also possible that bodybuilders who ate more protein were also more aware of their macronutrient intake and health conscious in general, and that the folks who ate less protein followed more of a “see food,” anything-goes bulk. And if this is the case, they may have also supplemented more intelligently. Or got more sleep. Or some combination of all of these factors. All of which could explain the differences in health.

For instance, it’s possible (though unlikely) that the high-protein bulking group gained less fat and had a more favorable blood lipid profile because they ate fewer carbs, not because they ate more protein. Or maybe the standard bulking group ate considerably more calories than they reported, which would explain why they had higher body fat levels.

Then again, it’s also possible that there is some inherent advantage to upping your protein intake while bulking.

Previous research shows that people who eat a high-protein diet either gain similar amounts or less fat than those who eat a low-protein diet, even when the high-protein diet contains more calories. This would explain why the bulkers who ate more protein found it easier to keep their body fat percentage lower.

There’s also no evidence that eating a high-protein diet negatively impacts blood biomarkers, which means there could be some advantage to getting more calories from protein than other “macros.”

For now, though, there isn’t enough research to show there’s much benefit of eating more than about 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight per day while bulking. That said, this is another hint that high-protein dieting is healthful and superior to other diets when it comes to optimizing body composition.

And if you want a clean, convenient, and delicious source of protein that makes hitting your protein target easier and more enjoyable, try Whey+ or Casein+.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Whey+ or Casein+. is right for you or if another supplement might be a better fit for your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: Eating a high-protein diet while bulking may help you gain less fat and stay healthier, although this may simply be due to helping you avoid overeating.

Fish oil boosts post-exercise recovery.

Source: “Impact of Varying Dosages of Fish Oil on Recovery and Soreness Following Eccentric Exercise” published on July 27, 2020 in Nutrients.

Most people know that to get the most out of training, you have to recover effectively.

That’s why they’ll try almost any gadget or gizmo to expedite the process, including compression garments, massage guns, and cryotherapy.

Sometimes, however, the best solutions aren’t quite so fancy-dan.

Take omega-3 fatty acids.

Scientists have known for a long time that omega-3 fatty acids have anti-inflammatory and pain-inhibiting properties, which is likely why it boosts post-exercise recovery.

What’s the best way to take fish oil to suppress soreness after exercise, though?

That’s what researchers at Kennesaw State University wanted to find out when they split 32 experienced weightlifters into 4 groups:

- A group that took 2 grams of omega-3 (1400 mg EPA+DHA) daily

- A group that took 4 grams of omega-3 (2800 mg EPA+DHA) daily

- A group that took 6 grams of omega-3 (4200mg EPA+DHA) daily

- A group that took a placebo daily

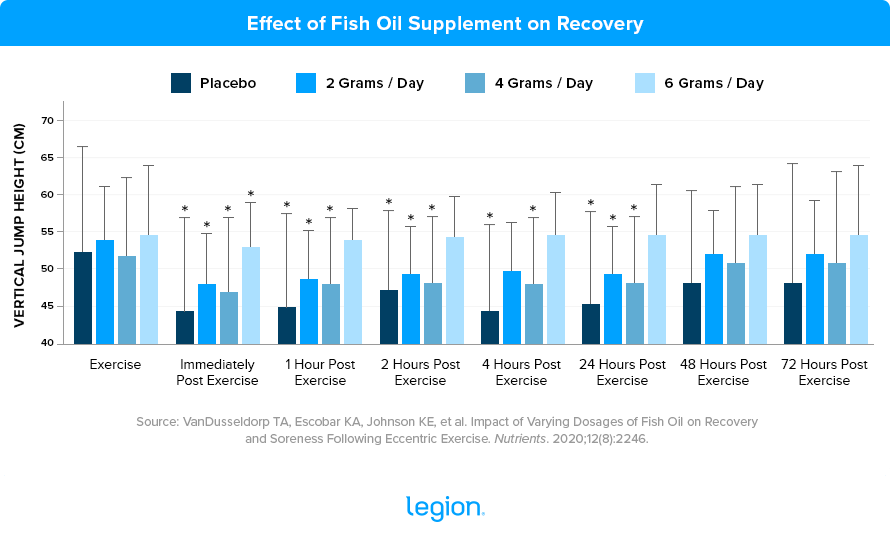

Each group took their fish oil supplement for 52 days. On day 49 of the study, all of the weightlifters did a grueling workout designed to cause muscle damage consisting of 10 sets of 8 reps of the squat using a 4-second eccentric (lowering) phase and 70% of their one-rep max, followed by 5 sets of 20 reps of bodyweight split jump-squats.

In the hours and days following the workout, the researchers took blood samples from the participants to understand how each supplement affected markers of muscle damage.

The results showed that creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase levels were similar in the placebo, 2-gram, and 4-gram groups but lower in the 6-gram group, suggesting that those who took 6 grams of fish oil suffered the least muscle damage.

To test physical recovery, the researchers also measured the participants’ vertical jump height in the hours and days after the workout. They found that the weightlifters in the 6-gram group had the smallest dip in performance and returned to full strength faster than all other groups:

The researchers tested physical performance using an agility, sprint, and strength test, too, but the results didn’t uncover anything noteworthy (though the 6-gram group tended to recover more fully after these tests than the other groups).

Finally, the researchers asked the weightlifters to rate how sore they felt and found that those in the 6-gram group experienced significantly less subjective soreness than the weightlifters in the other groups. The weightlifters in the 6-gram group also recovered quicker over the following days.

These findings somewhat jive with the results of previous studies. The only difference is that other studies have shown that fish oil boosts recovery at slightly lower doses than 6 grams per day (most suggest 4 grams is more than adequate).

There’s likely a simple explanation: The workout used in this study was brutal. If you did a challenging workout rather than a masochistic one, lower doses of fish oil are probably sufficient.

Bottom line, supplementing with 4-to-6 grams of omega-3 per day will likely improve your recovery from training in small but meaningful ways . . . at least in the short term.

This brings us to an important caveat, which is that reducing inflammation and muscle soreness isn’t always desirable. Inflammation is an important part of the muscle-building process, and although reducing it can help you feel better in the short-term, it may also undermine your long-term gains. This is why, for instance, anti-inflammatory medications like Ibuprofen and ice baths (which reduce swelling, soreness, and inflammation) seem to interfere with long-term muscle growth.

When weighing the pros and cons, I’d say the best course is to consume the clinically effective dose of omega-3s for supporting health, but no more, at least until there’s more research showing that these higher doses don’t interfere with your gains.

And if you’d like a 100% natural high-potency reesterified triglyceride fish oil made from deep-water Peruvian anchovies and sardines, check out Triton.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Triton is right for you, take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: Taking 4-to-6 grams of fish oil per day boosts post-exercise recovery and reduces soreness, but it could also interfere with muscle growth over time.

+ Scientific References

- Hautala, A. J., Kiviniemi, A. M., Mäkikallio, T. H., Kinnunen, H., Nissilä, S., Huikuri, H. V., & Tulppo, M. P. (2006). Individual differences in the responses to endurance and resistance training. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 96(5), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-005-0116-2

- Ahtiainen, J. P., Walker, S., Peltonen, H., Holviala, J., Sillanpää, E., Karavirta, L., Sallinen, J., Mikkola, J., Valkeinen, H., Mero, A., Hulmi, J. J., & Häkkinen, K. (2016). Heterogeneity in resistance training-induced muscle strength and mass responses in men and women of different ages. Age, 38(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11357-015-9870-1/FIGURES/5

- BOUCHARD, C., & RANKINEN, T. (n.d.). Individual differences in response to regular physical activ… : Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2001/06001/Individual_differences_in_response_to_regular.13.aspx

- Dalleck, L., Haney, D. E., Buchanan, C. A., & Weatherwax, R. M. (n.d.). (PDF) Does a personalised exercise prescription enhance training efficacy and limit training unresponsiveness? A randomised controlled trial. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311536467_Does_a_personalised_exercise_prescription_enhance_training_efficacy_and_limit_training_unresponsiveness_A_randomised_controlled_trial

- Montero, D., Lundby, C., Montero, D., & Lundby, C. (2017). Refuting the myth of non-response to exercise training: ‘non-responders’ do respond to higher dose of training. The Journal of Physiology, 595(11), 3377–3387. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP273480

- Moraes, W. M., Mendes, A. E. P., Lopes, M. M. M., & Maia, F. M. M. (n.d.). [PDF] Protein Overfeeding is Associated with Improved Lipid and Anthropometric Profile thus Lower Malondialdehyde Levels in Resistance-Trained Athletes. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317050180_Protein_Overfeeding_is_Associated_with_Improved_Lipid_and_Anthropometric_Profile_thus_Lower_Malondialdehyde_Levels_in_Resistance-Trained_Athletes

- Kreider, R. B. (1999). Dietary supplements and the promotion of muscle growth with resistance exercise. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 27(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199927020-00003

- Forbes, G. B., Brown, M. R., Welle, S. L., & Lipinski, B. A. (1986). Deliberate overfeeding in women and men: energy cost and composition of the weight gain. The British Journal of Nutrition, 56(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN19860080

- Tappy, L. (2004). Metabolic consequences of overfeeding in humans. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 7(6), 623–628. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200411000-00006

- Garthe, I., Raastad, T., Refsnes, P. E., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2013). Effect of nutritional intervention on body composition and performance in elite athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(3), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2011.643923

- Savini, I., Catani, M. V., Evangelista, D., Gasperi, V., & Avigliano, L. (2013). Obesity-Associated Oxidative Stress: Strategies Finalized to Improve Redox State. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14(5), 10497. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS140510497

- Morell, P., & Fiszman, S. (2017). Revisiting the role of protein-induced satiation and satiety. Food Hydrocolloids, 68, 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODHYD.2016.08.003

- Antonio, J., Peacock, C. A., Ellerbroek, A., Fromhoff, B., & Silver, T. (2014). The effects of consuming a high protein diet (4.4 g/kg/d) on body composition in resistance-trained individuals. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-19

- Antonio, J., Ellerbroek, A., Silver, T., Orris, S., Scheiner, M., Gonzalez, A., & Peacock, C. A. (2015). A high protein diet (3.4 g/kg/d) combined with a heavy resistance training program improves body composition in healthy trained men and women – a follow-up investigation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-015-0100-0

- Antonio, J., Ellerbroek, A., Silver, T., Vargas, L., & Peacock, C. (2016). The effects of a high protein diet on indices of health and body composition–a crossover trial in resistance-trained men. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-016-0114-2

- Van Dusseldorp, T. A., Escobar, K. A., Johnson, K. E., Stratton, M. T., Moriarty, T., Kerksick, C. M., Mangine, G. T., Holmes, A. J., Lee, M., Endito, M. R., & Mermier, C. M. (2020). Impact of Varying Dosages of Fish Oil on Recovery and Soreness Following Eccentric Exercise. Nutrients, 12(8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU12082246

- Marqués-Jiménez, D., Calleja-González, J., Arratibel, I., Delextrat, A., & Terrados, N. (2016). Are compression garments effective for the recovery of exercise-induced muscle damage? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Physiology & Behavior, 153, 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2015.10.027

- Fonda, B., & Sarabon, N. (2013). Effects of whole-body cryotherapy on recovery after hamstring damaging exercise: a crossover study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 23(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/SMS.12074

- Gunnarsdottir, I., Tomasson, H., Kiely, M., Martinéz, J. A., Bandarra, N. M., Morais, M. G., & Thorsdottir, I. (2008). Inclusion of fish or fish oil in weight-loss diets for young adults: effects on blood lipids. International Journal of Obesity 2008 32:7, 32(7), 1105–1112. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.64

- Kris-Etherton, P. M., Harris, W. S., & Appel, L. J. (2002). Fish Consumption, Fish Oil, Omega-3 Fatty Acids, and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation, 106(21), 2747–2757. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000038493.65177.94

- McVeigh, G. E., Brennan, G. M., Cohn, J. N., Finkelstein, S. M., Hayes, R. J., & Johnston, G. D. (1994). Fish oil improves arterial compliance in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis: A Journal of Vascular Biology, 14(9), 1425–1429. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.14.9.1425

- Morris, M. C., Sacks, F., & Rosner, B. (1993). Does fish oil lower blood pressure? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Circulation, 88(2), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.88.2.523

- Xin, G., & Eshaghi, H. (2021). Effect of omega‐3 fatty acids supplementation on indirect blood markers of exercise‐induced muscle damage: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Science & Nutrition, 9(11), 6429. https://doi.org/10.1002/FSN3.2598

- Tinsley, G. M., Gann, J. J., Huber, S. R., Andre, T. L., La Bounty, P. M., Bowden, R. G., Gordon, P. M., & Grandjean, P. W. (2017). Effects of Fish Oil Supplementation on Postresistance Exercise Muscle Soreness. Journal of Dietary Supplements, 14(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390211.2016.1205701

- Philpott, J. D., Donnelly, C., Walshe, I. H., MacKinley, E. E., Dick, J., Galloway, S. D. R., Tipton, K. D., & Witard, O. C. (2018). Adding Fish Oil to Whey Protein, Leucine, and Carbohydrate Over a Six-Week Supplementation Period Attenuates Muscle Soreness Following Eccentric Exercise in Competitive Soccer Players. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.2017-0161

- Jouris, K. B., McDaniel, J. L., & Weiss, E. P. (2011). The Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation on the Inflammatory Response to eccentric strength exercise. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 10(3), 432. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000354215.91342.08

- Tsuchiya, Y., Yanagimoto, K., Ueda, H., & Ochi, E. (2019). Supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid-rich fish oil attenuates muscle stiffness after eccentric contractions of human elbow flexors. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-019-0283-X

- Tsuchiya, Y., Yanagimoto, K., Nakazato, K., Hayamizu, K., & Ochi, E. (2016). Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids-rich fish oil supplementation attenuates strength loss and limited joint range of motion after eccentric contractions: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 116(6), 1179–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-016-3373-3

- Roberts, L. A., Raastad, T., Markworth, J. F., Figueiredo, V. C., Egner, I. M., Shield, A., Cameron-Smith, D., Coombes, J. S., & Peake, J. M. (2015). Post-exercise cold water immersion attenuates acute anabolic signalling and long-term adaptations in muscle to strength training. The Journal of Physiology, 593(Pt 18), 4285. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP270570

[ad_2]

Source link