[ad_1]

Hemp protein powder is a protein supplement made from ground hemp seeds.

It isn’t a luminary of the protein world like whey or casein, but its acclaim is growing, particularly among people who want plant-based, minimally processed protein supplements.

Not everyone is taken by hemp protein powder, though, with critics claiming that its amino acid profile is lacking, making it underpowered to support muscle growth.

In this article, we’re going to weigh up hemp protein powder’s benefits and drawbacks, so you can make an evidence-based decision about whether hemp protein is right for you.

What Is Hemp Protein Powder?

Hemp protein powder (also known as hemp seed protein powder) is a protein supplement made by milling pressed hemp seeds into powder.

It’s similar to hemp flour, except it goes through extra processing so that it contains more protein and less fiber.

Hemp Protein Powder: Benefits and Drawbacks

Many supplement companies wax lyrical about the benefits of hemp protein powder, but few detail its downsides.

Let’s see what science says about hemp protein powder’s benefits and drawbacks so you get the whole story.

Protein Quantity and Quality

One of the oft-touted benefits of hemp protein powder is that it’s a “complete” protein. “Complete” in this sense means it contains all nine essential amino acids, which are the amino acids that we must get from our diet.

Canny supplement marketers class hemp protein powder as “complete” because it sounds compelling to consumers, but it actually tells us little about its quality. Fortunately, research fills in the gaps that marketing leaves blank.

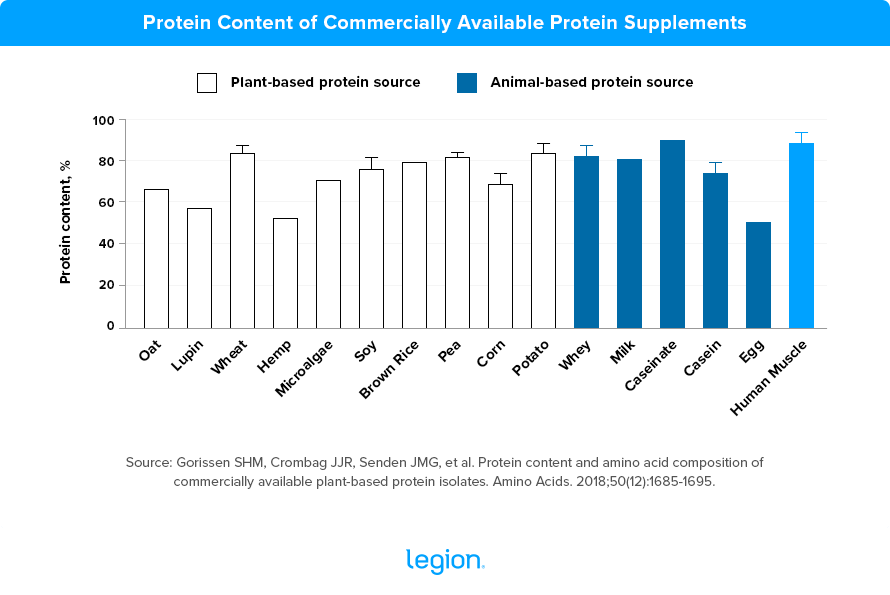

In a study conducted by scientists at Maastricht University, researchers analyzed and compared the protein quantity and quality of commercially available plant- and animal-based protein supplements. Their results showed that hemp protein powder contained the least amount of protein (51%) of all the protein products they investigated:

The researchers then analyzed the essential amino acid profile of each product and found that hemp protein powder contained the fourth lowest levels (23%)—only slightly more than oat protein (21%), which they identified as containing the least.

Importantly for weightlifters, hemp also contained the least leucine and comparatively low levels of isoleucine, valine, lysine, and phenylalanine, which all play a vital role in the muscle-building process.

In other words, hemp protein powder has all the markings of a quality protein source. However, it’s low in the amino acids that mean most to weightlifters, making it a second-string alternative to top-tier protein supplements such as whey protein powder and casein protein powder.

Digestibility

One of the major drawbacks of plant-based protein sources is that they’re difficult for your body to break down and absorb, which means you can’t use all the amino acids they contain.

This isn’t so much of an issue for hemp protein, though.

Research shows that hemp protein powder consists of 60-to-80% globulin (edestin) and 20-to-40% albumin, two kinds of protein the body can digest easily, which is why studies show that you utilize up to 92% of the protein in hemp protein powder.

(Note: Research suggests that heat-damaged proteins are less well digested. If you want the most digestible form of hemp protein, use a hemp protein powder made from cold-pressed seeds.)

Other Health Benefits

Unlike most protein supplements, hemp protein powder contains several nutrients that may provide additional health benefits, including:

- Fiber: Hemp protein powder is high in fiber, which means it may help to reduce your risk of illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and diverticulitis.

- Unsaturated Fat: Before hemp seeds are ground into powder, they’re pressed to extract their oil. Despite this process, powdered hemp seeds maintain ~13% of their oil, which typically contains more than 90% unsaturated fatty acids. This is important because unsaturated fats help you maintain good cardiovascular and metabolic health.

- Vitamins and Minerals: No research has looked at hemp protein powder specifically, but research on hemp meal (finely ground hemp seeds) shows it contains high amounts of vitamin E, thiamine, riboflavin, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, calcium, iron, sodium, manganese, zinc, and copper.

- Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Compounds: Hemp is a rich source of cannabinoids, lignanamides, flavonoids, stilbenoids, terpenoids, lignans, and alkaloids, which are compounds that have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects on the body and help stave off a raft of disorders such as metabolic disease, cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.

Better Alternatives to Hemp Protein Powder for Building Muscle

Hemp protein powder isn’t a terrible nutritional supplement. It contains plenty of fiber, some unsaturated fat, and a wealth of vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals, all of which confer health benefits.

However, the primary reason people use hemp protein powder is to support muscle growth, and this is where it comes a cropper. Hemp’s amino acid profile is poor overall and it’s particularly lacking in the amino acids that contribute most to muscle growth. It also contains less protein per gram than most every other commercially available protein supplement.

And that’s why even the best hemp protein powders can’t compete with whey, casein, or even rice and pea protein powder when it comes to aiding muscle growth.

So, if you’re looking to build muscle as effectively as possible, avoid hemp and plump for whey, casein, or rice and pea protein instead.

If you’re looking for a clean, convenient, and delicious source of whey, casein, or rice and pea protein, check out Legion’s Whey+ protein powder, Casein+ protein powder, and Plant+ protein powder.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Whey+, Casein+, or Plant+ are right for you or if another supplement might be a better fit for your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

FAQ #1: Hemp protein vs. Whey protein: Which is better?

If you want to build muscle, whey protein is superior.

Hemp protein powder contains less overall protein and less of the amino acids that most contribute to muscle growth than whey protein powder, which is why even the best hemp protein powders can’t compete with whey at supporting muscle growth.

And if you want a 100% natural and delicious whey protein supplement, try Whey+ protein powder.

FAQ #2: Hemp protein vs. Pea protein: Which is better?

If you’re looking to build muscle, pea protein is better.

Pea protein is easily digested and contains an abundance of leucine, which is the essential amino acid most responsible for muscle building. It’s also high in isoleucine, valine, and other essential amino acids, which is why it’s about as effective as whey protein for building muscle.

If you want a 100% natural plant-based protein powder with rice and pea protein and little carbohydrate and fat, try Plant+ protein powder.

FAQ #3: Is hemp protein good for you?

Yes.

Hemp protein powder contains some protein, plenty of fiber and unsaturated fat, and a wealth of vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals, all of which confer health benefits.

Its only downside is it doesn’t contain much high-quality protein, which means it isn’t the best option for people looking to build or maintain muscle.

FAQ #4: Is hemp protein “complete?”

Yes.

Hemp protein contains all nine essential amino acids, which is why many people consider it “complete.”

That said, hemp protein doesn’t contain enough leucine, isoleucine, valine, lysine, or phenylalanine to meet the World Health Organization’s minimum “amino acid requirements,” which means you wouldn’t get enough of these amino acids to maintain good health if hemp was your only protein source.

FAQ #5: How much protein is in hemp seeds?

Hemp seeds contain 31.6 grams of protein per 100 grams, which is ~9.5 grams of protein per 30-gram serving.

+ Scientific References

- van Vliet, S., Burd, N. A., & van Loon, L. J. C. (2015). The Skeletal Muscle Anabolic Response to Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Consumption. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(9), 1981–1991. https://doi.org/10.3945/JN.114.204305

- Tang, C. H., Ten, Z., Wang, X. S., & Yang, X. Q. (2006). Physicochemical and functional properties of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) protein isolate. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 54(23), 8945–8950. https://doi.org/10.1021/JF0619176

- Wang, Q., & Xiong, Y. L. (2019). Processing, Nutrition, and Functionality of Hempseed Protein: A Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 18(4), 936–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12450

- Pihlanto, A., Mattila, P., Mäkinen, S., & Pajari, A. M. (2017). Bioactivities of alternative protein sources and their potential health benefits. Food & Function, 8(10), 3443–3458. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7FO00302A

- House, J. D., Neufeld, J., & Leson, G. (2010). Evaluating the quality of protein from hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) products through the use of the protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score method. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 58(22), 11801–11807. https://doi.org/10.1021/JF102636B

- Sarwar, G. (1997). The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score method overestimates quality of proteins containing antinutritional factors and of poorly digestible proteins supplemented with limiting amino acids in rats. The Journal of Nutrition, 127(5), 758–764. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/127.5.758

- Rusu, I. E., Marc, R. A., Mureşan, C. C., Mureşan, A. E., Filip, M. R., Onica, B. M., Csaba, K. B., Alexa, E., Szanto, L., & Muste, S. (2021). Advanced Characterization of Hemp Flour (Cannabis sativa L.) from Dacia Secuieni and Zenit Varieties, Compared to Wheat Flour. Plants, 10(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/PLANTS10061237

- Callaway, J. C. (2004). Hempseed as a nutritional resource: An overview. Euphytica 2004 140:1, 140(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10681-004-4811-6

- Levi, F., Pasche, C., Lucchini, F., Chatenoud, L., Jacobs, D. R., & La Vecchia, C. (2000). Refined and whole grain cereals and the risk of oral, oesophageal and laryngeal cancer. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 54(6), 487–489. https://doi.org/10.1038/SJ.EJCN.1601043

- Aune, D., Chan, D. S. M., Greenwood, D. C., Vieira, A. R., Navarro Rosenblatt, D. A., Vieira, R., & Norat, T. (2012). Dietary fiber and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Annals of Oncology : Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 23(6), 1394–1402. https://doi.org/10.1093/ANNONC/MDR589

- Pereira, M. A., O’Reilly, E., Augustsson, K., Fraser, G. E., Goldbourt, U., Heitmann, B. L., Hallmans, G., Knekt, P., Liu, S., Pietinen, P., Spiegelman, D., Stevens, J., Virtamo, J., Willett, W. C., & Ascherio, A. (2004). Dietary fiber and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(4), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHINTE.164.4.370

- Multari, S., Neacsu, M., Scobbie, L., Cantlay, L., Duncan, G., Vaughan, N., Stewart, D., & Russell, W. R. (2016). Nutritional and Phytochemical Content of High-Protein Crops. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 64(41), 7800–7811. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.JAFC.6B00926

- Pojić, M., Mišan, A., Sakač, M., HadnaCrossed D Signev, T. D., Šarić, B., Milovanović, I., & HadnaCrossed D Signev, M. (2014). Characterization of byproducts originating from hemp oil processing. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 62(51), 12346–12442. https://doi.org/10.1021/JF5044426

- Lizarazo, C. I., Lampi, A. M., Liu, J., Sontag-Strohm, T., Piironen, V., & Stoddard, F. L. (2015). Nutritive quality and protein production from grain legumes in a boreal climate. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 95(10), 2053–2064. https://doi.org/10.1002/JSFA.6920

- Ulven, S. M., Leder, L., Elind, E., Ottestad, I., Christensen, J. J., Telle-Hansen, V. H., Skjetne, A. J., Raael, E., Sheikh, N. A., Holck, M., Torvik, K., Lamglait, A., Thyholt, K., Byfuglien, M. G., Granlund, L., Andersen, L. F., & Holven, K. B. (2016). Exchanging a few commercial, regularly consumed food items with improved fat quality reduces total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Nutrition, 116(8), 1383–1393. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114516003445

- Kromhout, D., Yasuda, S., Geleijnse, J. M., & Shimokawa, H. (2012). Fish oil and omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease: do they really work? European Heart Journal, 33(4), 436. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHR362

- Poudyal, H., Panchal, S. K., Diwan, V., & Brown, L. (2011). Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic syndrome: effects and emerging mechanisms of action. Progress in Lipid Research, 50(4), 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PLIPRES.2011.06.003

- Virtanen, J. K., Mursu, J., Voutilainen, S., Uusitupa, M., & Tuomainen, T. P. (2014). Serum omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor study. Diabetes Care, 37(1), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.2337/DC13-1504

- Rodriguez-Martin, N. M., Montserrat-De la Paz, S., Toscano, R., Grao-Cruces, E., Villanueva, A., Pedroche, J., Millan, F., & Millan-Linares, M. C. (2020). Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Protein Hydrolysates Promote Anti-Inflammatory Response in Primary Human Monocytes. Biomolecules, 10(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/BIOM10050803

- Pihlanto, A., Mattila, P., Mäkinen, S., & Pajari, A. M. (2017). Bioactivities of alternative protein sources and their potential health benefits. Food & Function, 8(10), 3443–3458. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7FO00302A

- Nagarkatti, P., Pandey, R., Rieder, S. A., Hegde, V. L., & Nagarkatti, M. (2009). Cannabinoids as novel anti-inflammatory drugs. Future Medicinal Chemistry, 1(7), 1333. https://doi.org/10.4155/FMC.09.93

- Leonard, W., Zhang, P., Ying, D., & Fang, Z. (2021). Lignanamides: sources, biosynthesis and potential health benefits – a minireview. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 61(8), 1404–1414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1759025

- Panche, A. N., Diwan, A. D., & Chandra, S. R. (2016). Flavonoids: an overview. Journal of Nutritional Science, 5, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/JNS.2016.41

- Akinwumi, B. C., Bordun, K. A. M., & Anderson, H. D. (2018). Biological Activities of Stilbenoids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS19030792

- Callaway, J. C. (2004). Hempseed as a nutritional resource: An overview. Euphytica 2004 140:1, 140(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10681-004-4811-6

- Thoppil, R. J., & Bishayee, A. (2011). Terpenoids as potential chemopreventive and therapeutic agents in liver cancer. World Journal of Hepatology, 3(9), 228. https://doi.org/10.4254/WJH.V3.I9.228

- Rodríguez-García, C., Sánchez-Quesada, C., Toledo, E., Delgado-Rodríguez, M., & Gaforio, J. J. (2019). Naturally Lignan-Rich Foods: A Dietary Tool for Health Promotion? Molecules, 24(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/MOLECULES24050917

- Qiu, S., Sun, H., Zhang, A. H., Xu, H. Y., Yan, G. L., Han, Y., & Wang, X. J. (2014). Natural alkaloids: basic aspects, biological roles, and future perspectives. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines, 12(6), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1875-5364(14)60063-7

- Mclaughlin, T., Ackerman, S. E., Shen, L., & Engleman, E. (2017). Role of innate and adaptive immunity in obesity-associated metabolic disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 127(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI88876

- Schain, M., & Kreisl, W. C. (2017). Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders-a Review. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/S11910-017-0733-2

- Rogero, M. M., & Calder, P. C. (2018). Obesity, Inflammation, Toll-Like Receptor 4 and Fatty Acids. Nutrients, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU10040432

- Mazidi, M., Shivappa, N., Wirth, M. D., Hebert, J. R., Mikhailidis, D. P., Kengne, A. P., & Banach, M. (2018). Dietary inflammatory index and cardiometabolic risk in US adults. Atherosclerosis, 276, 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHEROSCLEROSIS.2018.02.020

- Mariotti, F., Pueyo, M. E., Tomé, D., Bérot, S., Benamouzig, R., & Mahé, S. (2001). The influence of the albumin fraction on the bioavailability and postprandial utilization of pea protein given selectively to humans. The Journal of Nutrition, 131(6), 1706–1713. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/131.6.1706

- Babault, N., Christos Païzis, Deley, G., Laetitia Guérin-Deremaux, Marie-Hélène Saniez, Lefranc-Millot, C., & Allaert, F. A. (2015). Pea proteins oral supplementation promotes muscle thickness gains during resistance training: A double-blind, randomized, Placebo-controlled clinical trial vs. Whey protein. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-014-0064-5/FIGURES/4

[ad_2]

Source link