[ad_1]

It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share five scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn why kids quit playing sports, how to avoid jet lag, and how vitamin D affects your sleep.

Why kids quit playing sports.

Source: “A longitudinal transitional perspective on why adolescents choose to quit organized sport in Norway” published on July 9, 2021 in Psychology of Sport and Exercise.

Helping youngsters develop as athletes is a boon to their wellbeing for a number of reasons: it helps them learn to cooperate and compete with others and improves their self-confidence, work ethic, and health.

It’s also a priority for governments, since the more fit, active, talented young people are in a country, the larger the potential talent pool for the Olympics and other international competitions.

Most kids play at least a few sports growing up, but many quit in their teens (often during or after high school in the US). Some previous research suggests this may be because sports become more competitive, coaches become more ambitious and imperious, and training becomes more demanding, though other studies show that it could also be due to increased socializing, exploration of new interests, and academic pressures.

Scientists at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences conducted this study to better understand why kids cash in their athletic chips and move on to other games.

For 2 years, the researchers followed 34 Norwegian handball athletes (17 girls and 17 boys) aged 15-to-16 years old, 10 of whom (5 girls and 5 boys) quit playing during the study.

The researchers conducted a series of interviews with each athlete, probing many aspects of their athletic experiences such as the relationship with their coach, their focus on mastery versus competition, injuries, life outside of playing handball, their mindsets, and more.

The results revealed three themes that drove participants to quit:

- The sport became more about professionalism, competition, and exceptional performance and less about fun and skill development.

- They began to struggle to balance handball with school and other leisure-time activities.

- They became more interested in all of the other possibilities available to teenagers, like dating, travel, joining clubs, and so on.

Basically, these kids stopped playing handball when they found other activities that were more fun and fulfilling.

Although many adults dismiss children’s decisions as impulsive and half-baked (“they’ll find something new next week”), the researchers found that the kids in this study were pensive about their decision to quit handball. They reflected on the pros and cons of playing handball versus other activities and were clear-eyed about their goals and motivations for either continuing to play or quit.

The reason most of them stopped was that they determined handball wasn’t giving them the enjoyment, social interaction, and personal agency that it once did, and made a deliberate choice to pursue other activities that offered a better ROI.

Quitting was a wise choice for these kiddos.

This may sound obvious, but it goes against the grain of many parents and coaches who often push their kids to train and compete at the highest level as quickly as possible, and who sometimes prize winning over self-mastery, socializing, and skill-building. Many kids are also pressured into soldiering on with a sport long after it’s become stale, which can leave them acrid toward athletics as a whole.

Norway is an interesting case study in what happens when you take the opposite approach. Instead of focusing on competition, specialization, and performance, Norway emphasizes widespread participation, enjoyment, cooperation, and skill development from the time kids start playing sports up until their mid-to-late teens. Sports organizations don’t even keep score in games until kids are 13 years old.

Only after kids turn 15 or 16 do sports organizations start emphasizing competition and expert performance, and begin the process of winnowing the best athletes from the rest and providing them with rigorous training programs and competition.

This strategy may sound drippy to Americans, but it’s allowed Norway to punch well above its weight class in a variety of sports: Norway is one of the most dominant sporting nations in the world per capita. With just 5.3 million people, they’ve won more Winter Olympic medals (405) than any other country, including 148 golds. In 2018, they set a new record by winning 39 medals at the Winter Olympics, more than any other country in the history of the games.

Maybe they’re onto something?

TL;DR: Many young people quit playing competitive sports in their teens, but this is generally so they can pursue other interests, socialize with friends, and focus on their education. It’s not “giving up” so much as “moving on.”

The two things you must do to beat jet lag.

Source: “How To Travel the World Without Jet lag” published on June 1, 2009 in Sleep Medicine Clinics.

Jet lag occurs when you fly across multiple time zones, which frazzles your circadian rhythm and produces symptoms such as . . .

- difficulty initiating or maintaining nighttime sleep

- daytime sleepiness

- decreased alertness

- loss of concentration

- impaired physical performance

- fatigue

- irritability

- disorientation

- depressed mood

- and disturbed digestion.

In other words, jet lag sucks moist, stinky mongoose sphincter.

That’s why scientists at Rush University Medical Center wrote this study detailing the best evidence-based practices for avoiding it.

Here are the highlights:

- First, and most importantly, your circadian rhythm is predominantly dictated by your exposure to light. Thus, controlling light exposure is the single best lever you can pull to nip jet lag in the bud. For example, wearing light blocking glasses, staying up later or going to bed earlier, and using a light therapy lamp can help quickly shift your circadian rhythm.

- The best way to beat jet lag is to begin shifting your circadian rhythm (through controlled light exposure) several days before you travel. While you can still take the edge off jet lag after you arrive with the right methods, you’ll be dragging your feet much more than if you’d started earlier.

- Taking melatonin at carefully timed intervals may also help you shift your circadian rhythm slightly faster (though it’s far less important than controlling your light exposure).

- You can’t entirely eliminate the effects of jet lag, only minimize them. Even if you “feel fine,” your physical and mental performance will still probably sag for the first few days in a new location.

- Jet lag is mildest when flying east to west and harshest when flying west to east. For example, you’ll probably experience more jet lag flying from the US to Europe than vice versa.

- Supplements like caffeine can help reduce the symptoms of jet lag, but they don’t prevent it or significantly impact your circadian rhythm.

Since controlling your light exposure is the biggest factor in fighting jet lag, it’s worth unraveling what this looks like in more detail.

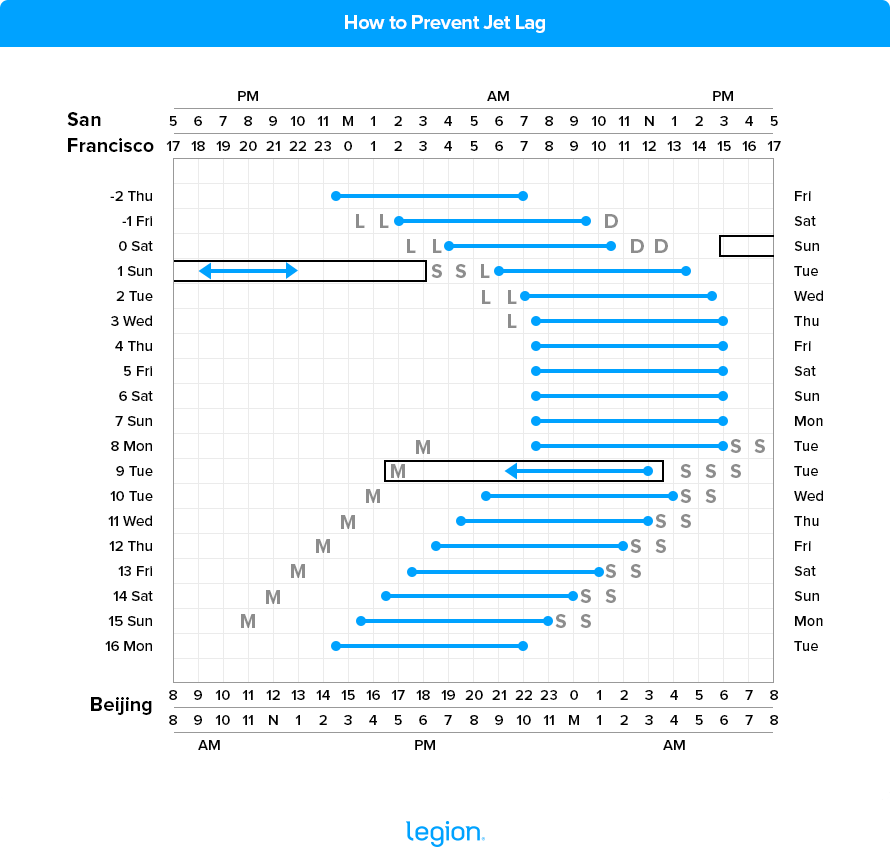

Let’s say you’re traveling from San Francisco to Beijing. In this case, you’re phase advancing (shifting your circadian rhythm forward) by 15 hours. Two days before you travel you’d stay up 2 hours later than normal and expose yourself to bright light (ideally from a light therapy lamp like this one) for 20-to-30 minutes during that time. Don’t worry about the precise timing of the light exposure during this pre-bed window, but a good rule of thumb is to place it about 30-to-60 minutes before bed.

The next morning, you’d avoid bright light for at least an hour after waking. In the evening, you’d push your bedtime back another two hours and again use light exposure sometime before bed. The next (second) morning, you’d again avoid bright light the first hour after waking.

After arriving in Beijing, you’d continue this process for your first two nights, except you’d no longer need to avoid bright light in the mornings.

When you fly back, you’d follow the same process in reverse, although you can instead change your circadian rhythm by an hour per day instead of two (since flying west generally produces less jet lag than flying east). The researchers also believe that melatonin is generally more beneficial when shifting your circadian rhythm westward (phase delaying). To use it, you’d take 3 mg of melatonin ~4.5 hours before bedtime. (And if you’re interested in a 100% natural sleep supplement that helps you fall asleep faster, stay asleep longer, and wake up feeling more rested, which also includes melatonin, try Lunar).

There are a lot of moving pieces to this puzzle, but the most important thing to get right is to start shifting your circadian rhythm (by either staying up or turning in earlier) about 2 days before you fly, and using light exposure to cement these changes.

Here’s a chart explaining when to go to sleep, wake up, expose yourself to light, or take melatonin, using the same example of flying from San Francisco to Beijing:

(“L” stands for light from a light therapy lamp, “S” stands for sunlight, and “M” stands for 3 mg of melatonin).

And where does caffeine fit into all of this?

Taking some when you feel groggy can help put some pep in your step, but it doesn’t actually help change your circadian rhythm or propensity for jet lag.

TL;DR: The best way to minimize jet lag is to begin changing your circadian rhythm 2 days before you travel and strategically control your exposure to light to cement these changes.

Vitamin D may help you sleep better.

Source: “Vitamin D Supplementation and Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies” published on February 28, 2022 in Nutrients.

Scientists have known for some time that there’s a connection between vitamin D and sleep.

Observational studies show that vitamin D deficiency is associated with an increased risk of sleep difficulties, poor sleep quality, short sleep duration, and waking up during the night, while people with sleep disorders are more likely to be vitamin D deficient.

As is the case with all observational studies, though, it’s difficult to pinpoint the cause of the connection.

For instance, vitamin D is involved in the production of melatonin, the hormone that’s responsible for regulating our circadian rhythm, which makes it easy to see how being deficient in D could disrupt your sleep.

However, our bodies synthesize vitamin D when we’re exposed to sunlight, and it seems equally plausible that people who sleep badly are more likely to get less sun exposure (they may sleep later in the day or take daytime naps, for example), reducing how much vitamin D they can generate.

In other words, we don’t know if vitamin D deficiency causes poor sleep or if it’s the other way around.

That’s why scientists at Zayed University performed a meta-analysis on the highest-quality studies looking at the relationship between vitamin D and sleep.

The researchers scanned several databases and found 19 studies worth examining, 13 of which were randomized controlled trials.

During their analysis, the researchers found that most of the available studies were difficult to compare. The methods varied drastically, measured different things, and reported the results in different ways, all of which made it hard to draw any useful conclusions.

That said, one clear finding was that supplementing with vitamin D was associated with significantly improved sleep quality.

When you look at the body of the evidence—a mechanistic explanation for how vitamin D can improve sleep, observational studies showing a link between vitamin D deficiency and poor sleep, and the present review showing that vitamin D supplements improve sleep quality—it’s fair to say that keeping your vitamin D levels topped off probably improves your sleep quality.

And if you want a multivitamin that contains a clinically effective dose of vitamin D, as well as 30 other ingredients designed to enhance your health and mood and reduce stress, fatigue, and anxiety, try Triumph for men and women.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Triumph is right for you or if another supplement might be a better fit for your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: Supplementing with vitamin D probably improves sleep quality, although the relationship between vitamin D and sleep is still poorly understood.

+ Scientific References

- Bergeron, M. F., Mountjoy, M., Armstrong, N., Chia, M., Côté, J., Emery, C. A., Faigenbaum, A., Hall, G., Kriemler, S., Léglise, M., Malina, R. M., Pensgaard, A. M., Sanchez, A., Soligard, T., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Van Mechelen, W., Weissensteiner, J. R., & Engebretsen, L. (2015). International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(13), 843–851. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2015-094962

- Dahl, R. E., Allen, N. B., Wilbrecht, L., & Suleiman, A. B. (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature, 554(7693), 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE25770

- Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

- Bentzen, M., Hordvik, M., Stenersen, M. H., & Solstad, B. E. (2021). A longitudinal transitional perspective on why adolescents choose to quit organized sport in Norway. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 56, 102015. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHSPORT.2021.102015

- Eastman, C. I., & Burgess, H. J. (2009). How To Travel the World Without Jet lag. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 4(2), 241. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSMC.2009.02.006

- Lemmer, B., Kern, R. I., Nold, G., & Lohrer, H. (2002). Jet lag in athletes after eastward and westward time-zone transition. Chronobiology International, 19(4), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1081/CBI-120005391

- Waterhouse, J., Edwards, B., Nevill, A., Carvalho, S., Atkinson, G., Buckley, P., Reilly, T., Godfrey, R., & Ramsay, R. (2002). Identifying some determinants of “jet lag” and its symptoms: a study of athletes and other travellers. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSM.36.1.54

- J E Wright, J A Vogel, J B Sampson, J J Knapik, J F Patton, & W L Daniels. (n.d.). Effects of travel across time zones (jet-lag) on exercise capacity and performance – PubMed. Retrieved June 30, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6838449/

- H Lynn Rogers, & Sandra M Reilly. (n.d.). A survey of the health experiences of international business travelers. Part One–Physiological aspects – PubMed. Retrieved June 30, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12400229/

- Eastman, C. I., & Burgess, H. J. (2009). How To Travel the World Without Jet lag. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 4(2), 241. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSMC.2009.02.006

- Abboud, M. (2022). Vitamin D Supplementation and Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients 2022, Vol. 14, Page 1076, 14(5), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU14051076

- Gao, Q., Kou, T., Zhuang, B., Ren, Y., Dong, X., & Wang, Q. (2018). The Association between Vitamin D Deficiency and Sleep Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 10(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU10101395

- Yan, S., Tian, Z., Zhao, H., Wang, C., Pan, Y., Yao, N., Guo, Y., Wang, H., Li, B., & Cui, W. (2020). A meta-analysis: Does vitamin D play a promising role in sleep disorders? Food Science & Nutrition, 8(10), 5696–5709. https://doi.org/10.1002/FSN3.1867

- Patrick, R. P., & Ames, B. N. (2015). Vitamin D and the omega-3 fatty acids control serotonin synthesis and action, part 2: relevance for ADHD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive behavior. The FASEB Journal, 29(6), 2207–2222. https://doi.org/10.1096/FJ.14-268342

- Romano, F., Muscogiuri, G., Di Benedetto, E., Zhukouskaya, V. V., Barrea, L., Savastano, S., Colao, A., & Di Somma, C. (2020). Vitamin D and Sleep Regulation: Is there a Role for Vitamin D? Current Pharmaceutical Design, 26(21), 2492–2496. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612826666200310145935

- Abboud, M. (2022). Vitamin D Supplementation and Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients 2022, Vol. 14, Page 1076, 14(5), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU14051076

[ad_2]

Source link