[ad_1]

One of the most fussed-over topics in fitness is whether you should let your knees go over your toes in the squat.

Some say that allowing your knees to “track” beyond your toes puts stress on your knees and is a surefire way to cause pain and injury.

Others say preventing your knees from traveling forward is the real danger. Doing so might take some of the strain off your knees, but it increases your risk of hurting your hips or spraining your back.

Who’s right?

Keep reading for an evidence-based answer.

Should Your Knees Go Over Your Toes When You Squat?

While its origin is uncertain, many people believe the idea that your knees should stay behind your toes while squatting stems from a 1974 study published in the International Series on Sport Sciences book series.

In that study, the researchers found that the participant whose knees traveled the furthest forward during the squat also experienced the greatest shear force (a force that acts on one part of the body in one direction and another in the opposite direction) on the knee joint.

Since shear forces increase the stress on a joint and can cause pain or injury, the researchers concluded that diligent squatters should prevent their knees from traveling over their toes or else pay the piper.

Of course, this was just one study. . . with only 12 participants. . . that reported data for just 3. . . didn’t control how deep the participants squatted. . . and didn’t go into detail about the squat technique the participants employed. All of the weightlifters were also men, so we don’t know how including women might have changed the results.

All of which is why most scientists look askance at its findings.

Another knock on this study is that it only considered a single joint—the knee. The squat involves several joints working synergistically. As such, any recommendations about best practice should investigate how knee travel affects biomechanics as a whole rather than focusing solely on the knee.

Fortunately, research conducted by scientists at The University of Memphis did just this.

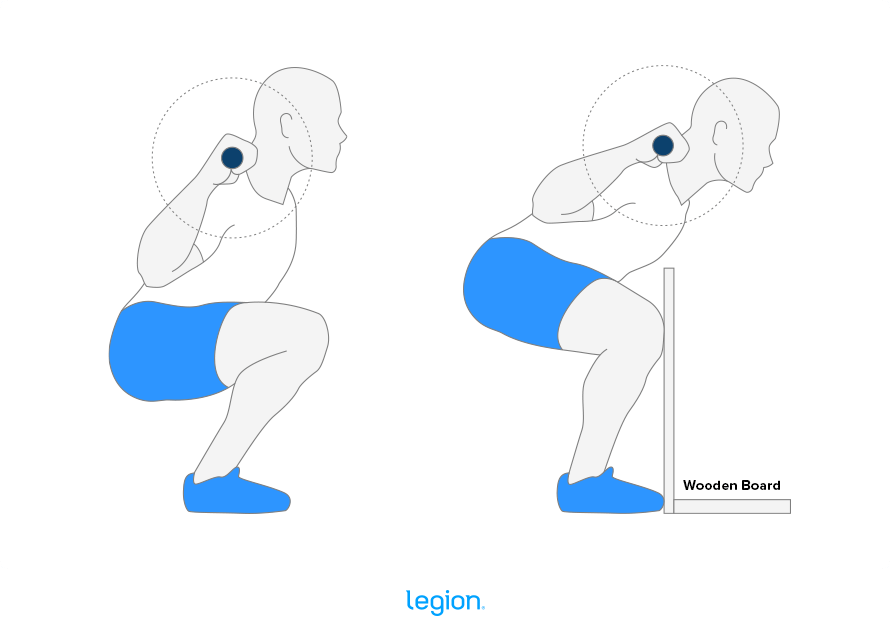

In this study, the participants performed two versions of the back squat: One where their knees could move forward freely (unrestricted) and one where a wooden board prevented their knees from traveling past their toes (restricted). Here’s how each squat looked:

The results showed that when participants allowed their knees to move beyond their toes, knee torque (force acting on the knee joint) increased from ~117 Newton-meters (N⋅m) in the restricted squat to ~150 N⋅m in the unrestricted squat. This meant knee torque increased by ~28% when their knees went over their toes, which sounds bad at first blush, but is still well within the limits of what your knees can handle.

What’s more, the folks who didn’t let their knees move beyond their toes also experienced significantly more stress on the hips. Specifically, keeping their knees from moving over their toes increased stress on their hips from ~28 N⋅m in the knees-over-toes squat to ~302 N⋅m in the restricted squat—an increase of 979%.

In other words, keeping the knee from moving over the toes slightly reduced stress on the knee but significantly increased stress on the hip.

Another study conducted by scientists at the Institute for Biomechanics reached a similar conclusion when it found that preventing the knees from moving over the toes reduced stress on the knee joint but significantly increased stress on the lower back.

That said, the amount of stress on the knees, hips, and lower back in each of these studies was still within a healthy, acceptable range and unlikely to cause any problems. Thus, there’s no reason to try to deliberately prevent your knees from going past your toes or force them in that direction. Instead, it’s best to focus on other aspects of your form, and let your knees wander as far forward as they like.

How to Avoid Knee Pain in the Squat

Now that we know that it’s safe to allow your knees to pass your toes in the squat, here are some tips to ensure your knees stay pain-free while squatting.

1. Keep your entire sole on the floor.

Although it’s safe for your knees to pass your toes while squatting, allowing them to pitch too far forward can lead to injury. That said, this is unlikely to happen unless your center of gravity shifts towards your toes, causing your heels to feel “light” or lift off the floor.

To avoid this, you must establish a stable base where your entire sole stays planted on the floor and your weight is centered over your midfoot.

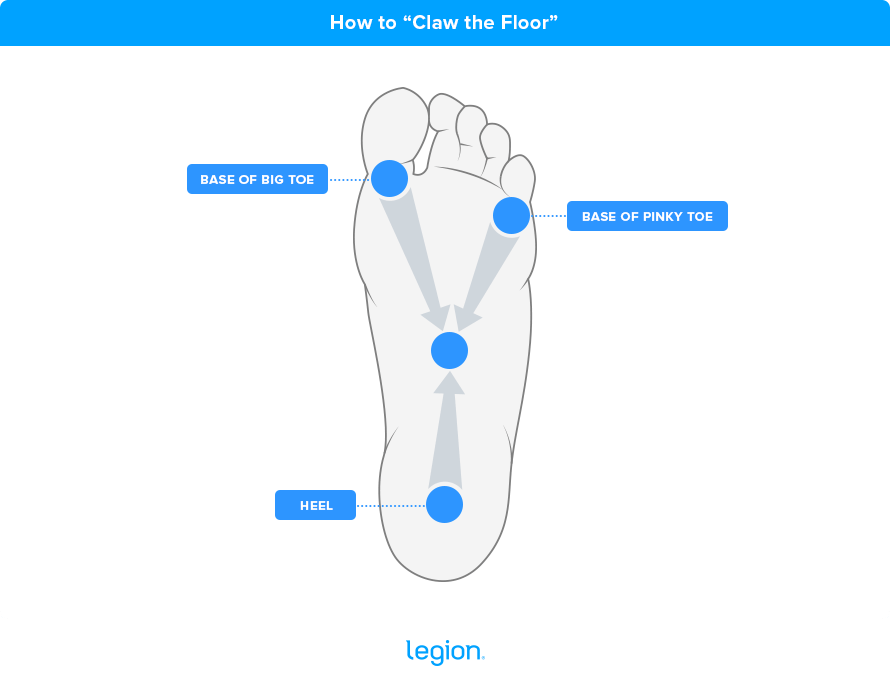

A good cue to help create a stable base is “claw the floor.” Get under the bar in the squat rack, adjust your feet so they’re a little wider than shoulder-width apart with your toes pointing out about 30-to-35 degrees (around 2 and 10 o’clock), and then imagine clawing” the floor by pulling your big toe, pinky toe, and heel towards the center of your foot.

This tenses the muscles in your feet and lower legs, which creates a stable, efficient base when squatting.

Here’s an illustration to help you visualize this:

2. Push your knees in the same direction as your toes.

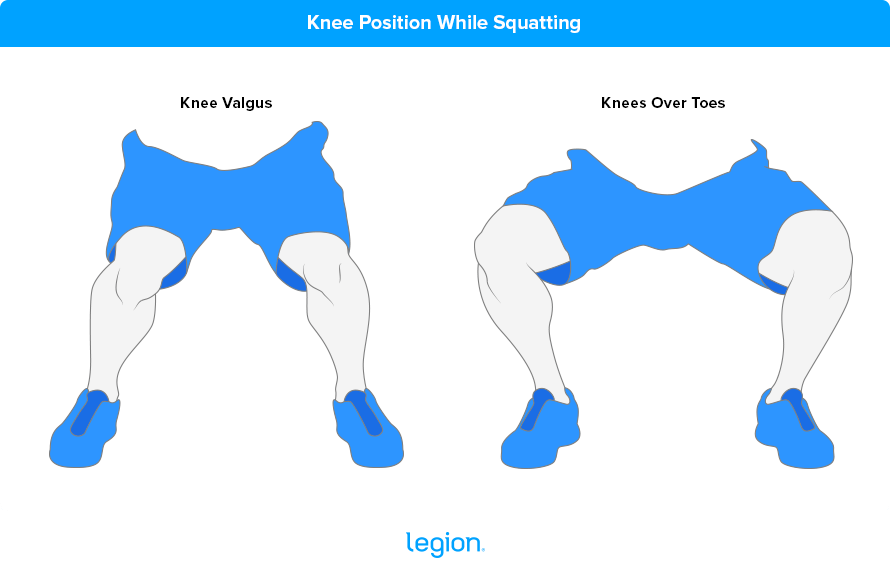

Knee valgus refers to a movement pattern where your knees “cave in” towards each other when you squat, which Mrs increase your risk of injury and impair your performance.

To avoid knee valgus, drive your knees outward in the same direction as your toes while squatting. Here’s how it should look:

A good cue to prevent knee valgus is “spread the floor with your feet.” As you squat, imagine spreading the floor apart with your feet by driving your feet into the ground and away from each other. Your feet won’t actually move, but this will help your knees move in the right direction.

It’s worth noting that not everyone experiences knee valgus. Instead, their knees track over their toes naturally, so they don’t need to consciously think about pushing their knees to the side and can instead focus on other elements of their technique.

3. Squat as deep as you comfortably can.

According to many weightlifters, squatting “to parallel” or below (the point at which your upper leg is parallel to the floor or deeper) is safer than shallower squats (often called partial squats) because it allows your hamstrings to contribute more to the exercise , taking some of the stress off the ligaments in your knees, and prevents you from using weights that are too heavy for your joints to safely handle.

In reality, though, research shows that squatting below, above, or to parallel places about the same amount of stress on your knees.

That said, you should still generally squat as deep as you comfortably can because deeper squats train your muscles through a longer range of motion and in a more stretched positionwhich is generally better for muscle growth.

However, if you find deep squatting uncomfortable or painful but shallow squats comfortable, don’t feel too guilty about cutting your depth short.

Some “movement gurus” claim that basically everyone can perform a deep, ass-to-grass squat if they’re diligent about stretching and doing mobility exercises, but this isn’t true. As Dean Somerset points out in an excellent article on this topic, the depth of your squat is largely delimited by the angle and depth of your hip joint.

Generally, people with deeper hip sockets (sometimes referred to as “Celtic” or “Scottish” hip, as this is more common in people of Northern European descent) will have trouble squatting to depth, whereas people with shallow hip sockets (sometimes referred to as “Dalmatian hip,” as this is more common among people of Eastern European descent) generally have an easier time squatting deep.

In other words, you should squat as deep as you can without pain or discomfort, but don’t force it.

+ Scientific References

- Ariel, BG (1974). Biomechanical analysis of the knee joint during deep knee bends with heavy load. Biomechanics IV, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-02612-8_7

- Hartmann, H., Wirth, K., & Klusemann, M. (2013). Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ), 43(10), 993–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-013-0073-6

- Andrew C Fry, J Chadwick Smith, & Brian K Schilling. (n.d.). Effect of knee position on hip and knee torques during the barbell squat – PubMed. Retrieved August 8, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14636100/

- Schoenfeld, BJ (2010). Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3497–3506. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181BAC2D7

- List, R., Gülay, T., Stoop, M., & Lorenzetti, S. (2013). Kinematics of the trunk and the lower extremities during restricted and unrestricted squats. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(6), 1529–1538. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3182736034

- Reece, MB, Arnold, GP, Nasir, S., Wang, WW, & Abboud, R. (2020). Barbell back squat: How do resistance bands affect muscle activation and knee kinematics? BMJ Open Sport and Exercise Medicine, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJSEM-2019-000610

- Flores, V., Becker, J., Burkhardt, E., & Cotter, J. (2020). Knee Kinetics During Squats of Varying Loads and Depths in Recreationally Trained Women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(7), 1945–1952. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002509

- Cotter, JA, Chaudhari, AM, Jamison, ST, & Devor, ST (2013). Knee Joint Kinetics in Relation to Commonly Prescribed Squat Loads and Depths. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research / National Strength & Conditioning Association, 27(7), 1765. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3182773319

- Bloomquist, K., Langberg, H., Karlsen, S., Madsgaard, S., Boesen, M., & Raastad, T. (2013). Effect of range of motion in heavy load squatting on muscle and tendon adaptations. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(8), 2133–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-013-2642-7

[ad_2]

Source link